Our Verdict

An elegantly simple adventure that proves this new genre has legs.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A new strand game following in the footsteps of Death Stranding.

Release date July 7, 2022

Developer Strange Scaffold

Publisher Modern Wolf

Reviewed on RTX 3080 Ti, Intel i7-8086K, 16GB RAM

Multiplayer? No

Link Steam page

I don't pay much attention to my humble mouse. Like a limb, I use it every day and would struggle without it, but when was the last time I gave it any consideration? Aside from when I need to charge it, I just let it get on with things. Witch Strandings, though, puts the peripheral front-and-centre, making your cursor the hero and, with few exceptions, the only way you can interact with its doomed world.

Back in 2019, discussing what genre Death Stranding slotted into, Hideo Kojima claimed it was something new: a strand game. The defining feature of this new genre was forging social connections, which in the case of Death Stranding was done by delivering packages and linking up the disparate communities of human survivors. A mix, then, of walking sims and community-minded games like Stardew Valley and Animal Crossing.

Despite being a brief, minimalist game where you play a wee ball of light on a quest to save a forest and its depressed critters from a witch's curse, Witch Strandings is absolutely a sibling to Death Stranding. These depressed critters, who were once human, need a friend, you see, and for that friend to deliver food and medicine to cure what ails them.

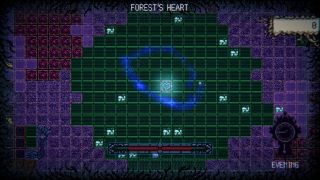

Complicating this quest is the forest itself, as it would very much like to kill you. Rushing water, sharp thorns, quicksand and evil hexes will get in your way, blocking your progress through this haunting world. Then there's the calm water, mud and other terrain features that don't block your way but do change how you move. Moving through the water with your cursor, you'll find you have a bit less control than usual, as you build up momentum and then keep floating forwards even once you've stopped moving your mouse. Get stuck in the mud, meanwhile, and you'll have to drag yourself out, tugging the mouse to free yourself.

It's surprisingly effective at communicating the challenges of walking through rough terrain, even without the elaborate 3D geometry and stumbling hero of Death Stranding. And since every flick of the mouse makes you veer off in that direction, you're always connected to the world. It might be made up of 2D tiles, but this raw interactivity means that it never feels anything less than tangible.

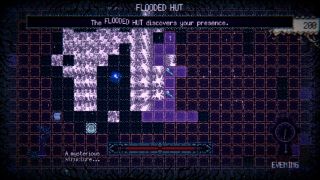

A lot of atmosphere has been packed into this lo-fi, abstract setup, and it's impressive how ominous it all feels. When I encountered a hollowed-out tree containing a whole bunch of red skulls, which I discovered would kill anyone I gifted them to, I felt like I was stuck in the site of some ritual murder, buzzing with evil energy, not hanging out in a blocky circle surrounded by cartoon bones. The audio helps a lot, too, with the whimsical tune accompanying your journey occasionally getting drowned out by discordant noise layered on top of it.

These unsettling touches reach their zenith on the approach to the witch's domain, a sprawling corridor of thorns that seems to go on forever even if it will realistically take you a minute to traverse. But in the context of this bite-sized game, it's a huge chunk of hostile terrain, with that threatening noise accompanying you the whole way.

Mind map

After a couple of hours spent exploring the forest, I stopped really seeing the tiles, with my mind instead translating them into thickets, bogs and lakes, which I'd then need to find a path through, or at least imagine what path I could create with the right tools. Scattered around the forest are myriad objects that push back against the threats the witch has put in your way, turning the surrounding area into safe tiles.

Initially, you'll need to drag these objects, one-by-one, and then deposit them in the most effective location—this is also how you deliver items to the forest's unfortunate residents. Conveniently, the areas any items neutralise remain clear even once you've picked the item up, with the water, quicksand or whatever only returning once you've plonked it down in a new area. Eventually you'll get some storage space where you can deposit an item for later use—a rare moment where you'll use your keyboard, hitting G, instead of your mouse—which means you can carry two at a time.

By making you drag things around for much of the game, the addition of one simple inventory block feels like a genuinely meaningful upgrade. It's as empowering as a flashy new ability or complex system, immediately making deliveries and exploration so much easier, in turn making you feel more capable and confident.

Once I'd created permanent paths through the obstacles and etched the map in my mind, I was speeding through the world with wild abandon. After hours of caution, I was free to let rip, swinging my mouse around like a maniac. The forest was a blur as I tore through it, laughing in the face of danger. And that's how I found myself drowning in the middle of a lake I'd accidentally rushed into. This was in part because of my own recklessness, sure, but Witch Strandings has to accept some of the blame.

See, the screen only moves when you get close to the top or bottom edge, making it hard to know what's ahead of you. This might be by design, to retain some mystery, but this limitation does not exist when you move left or right, when your view changes much earlier. This becomes more of an annoyance when you take into account the large health bar at the bottom of the screen and frequent notifications you get at the top, substantially obscuring your vision. If you're zoomed-in, you can pull back to see more of your immediate surroundings, and I found myself playing that way almost exclusively—but I still had to get near the edge before I could start to see what was coming up.

Finding new routes across the map and opening up previously blocked areas gave me a lovely serotonin boost, but I found myself less interested in my actual quest. The discarded notes and descriptions of ruined buildings—which, I should add, can be reconstructed, increasing your health and giving you handy fast travel options—and sad animals are all evocatively written, each feeling like a snippet from a tragic biography or historical account, but they are all brief and enigmatic, never giving you more than vibes.

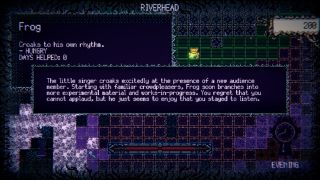

I liked Frog the most, but that's because I encountered my amphibian pal more frequently than the others, and they typically needed items that were easier to access from that location, making them simpler to cheer up. I didn't learn more about them or forge some kind of bond, spoken or otherwise. It's just a frog who was once a person and I gave them some food and drink a few times. It ends up undermining the premise—I'm never really encouraged to care about these characters I'm meant to be helping.

The minimalism works in its favour most of the time, however, elegantly showcasing the pillars of this nascent genre without the multitude of complex systems seen in Death Stranding. When Kojima started positioning it as the vanguard of a new genre, I scoffed. Now that I'm seeing it again with such a different style, but still clearly within the same family of games, I'm a lot more convinced. And I'd like to see more.

Disclosure: Strange Scaffold's creative director Xalavier Nelson Jr. has previously contributed to PC Gamer.

An elegantly simple adventure that proves this new genre has legs.

Fraser is the UK online editor and has actually met The Internet in person. With over a decade of experience, he's been around the block a few times, serving as a freelancer, news editor and prolific reviewer. Strategy games have been a 30-year-long obsession, from tiny RTSs to sprawling political sims, and he never turns down the chance to rave about Total War or Crusader Kings. He's also been known to set up shop in the latest MMO and likes to wind down with an endlessly deep, systemic RPG. These days, when he's not editing, he can usually be found writing features that are 1,000 words too long or talking about his dog.