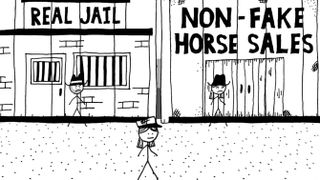

West of Loathing wasn't just a game with jokes in it, it was 'a game made out of jokes'

Designer Zack Johnson, in a talk at GDC 2018, explains how humor drives design in the comedy western RPG.

Zack Johnson, designer of open world comedy RPG West of Loathing, detailed the difference between a comedy game and a game with just some comedy in it during two talks he gave at GDC 2018 on Tuesday and Wednesday.

"Instead of a game with jokes in it, which happens all the time," Johnson said of West of Loathing, "this was sort of a game made out of jokes."

With humor being the primary focus of West of Loathing, and funny text appearing in everything from item descriptions to conversations to menu options, Johnson didn't want to throw roadblocks in the path of players who were bent on discovering every last bit of humor. Combat, therefore, which some reviewers criticized as being too easy, was easy by design.

As Johnson put it during his talk: "A joke is better than a good thing that's harder to make than a joke." You may have to read that a few times before it makes sense, but Johnson cited two of the gambling minigames in West of Loathing as example. The first game, poker, was something he agonized over and kept putting off during Loathing's development.

"It was a bunch of work," he said, "it resulted in this thing that was not particularly interesting, nobody talks about it." The poker game wasn't bad, in other words, it just wasn't funny.

"If there's a puzzle that requires a needle as its solution, we don't want the player to live in a world where there is only one needle"

The other game, found in the town of Breadwood, was called Pharaoh, and it was a game in which players simply lie about how many Egyptian pharaohs they could name. "That works, right?" Johnson said. "That is actually kind of funny."

The poker game took 268 lines of scripting, and was "not funny at all," admits Johnson. "The Pharoah game was 89 lines of script." That brings us back to Johnson's statement, that a joke is better than something good that is harder to make than a joke.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Puzzles, too, were designed to not be so challenging that they'd slow a player down for long, and while there are a few pretty complex puzzles in the game, they're off the beaten path and not required to make progress.

"If there's a puzzle that requires a needle as its solution," Johnson said, "we don't want the player to live in a world where there is only one needle, and if you didn't find it you can't get past the puzzle. So we just decided to put the needle in every haystack."

Johnson also spoke about the value of the narrator of West of Loathing.

"The narrator as sort of an honest character and honest reflection as who we are as writers also lets us be a little self-deprecating about stuff," he said, "which is a fantastic way to cover up fundamental flaws with your game, act like they're on purpose. 'We meant to do that, because isn't that funny?'"

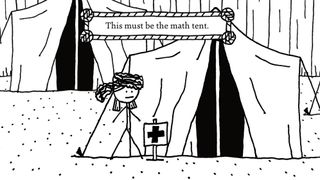

Does this room have a Couple of Pointless Gags?

Zack Johnson

Breaking the fourth wall, as the narrator does from time to time, is also more than just a gag: it's a way to simply and plainly give important information to the player. When players reached the final cutscene in West of Loathing, said Johnson, "It just tells you, this is not gonna change anything about your character or the state of the world, you can just watch this cutscene and then you can leave and do something else and then you can come back and do it again.

"I wish [more] games sort of had the confidence to let you know stuff like that," he continued, "because there's nothing more annoying to me than getting 40 hours into some RPG and then not knowing that I'm about to do something that means I should have saved, or have to revert to an hour ago."

Johnson also revealed a spreadsheet used during development of the game to track the status of dialogue, interactions, items, and monsters in each of the game's locations. One column of the spreadsheet was labeled CPG.

"CPG was my metric for whether this was a Loathing game," Johnson explained. "Does this room have a Couple of Pointless Gags?"

He referred to an area of the game where the player could explain to another character how mining equipment worked, despite not knowing how mining equipment worked, thus earning a perk called 'Minesplaining.'

"That stuff," Johnson said, "I think that is where a lot of the kind of memorable soul of the game lives."

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.

Most Popular