Two hours with Thimbleweed Park, the new adventure game from the creator of Monkey Island

A brutal murder brings two FBI agents to Thimbleweed Park, a strange town filled with secrets.

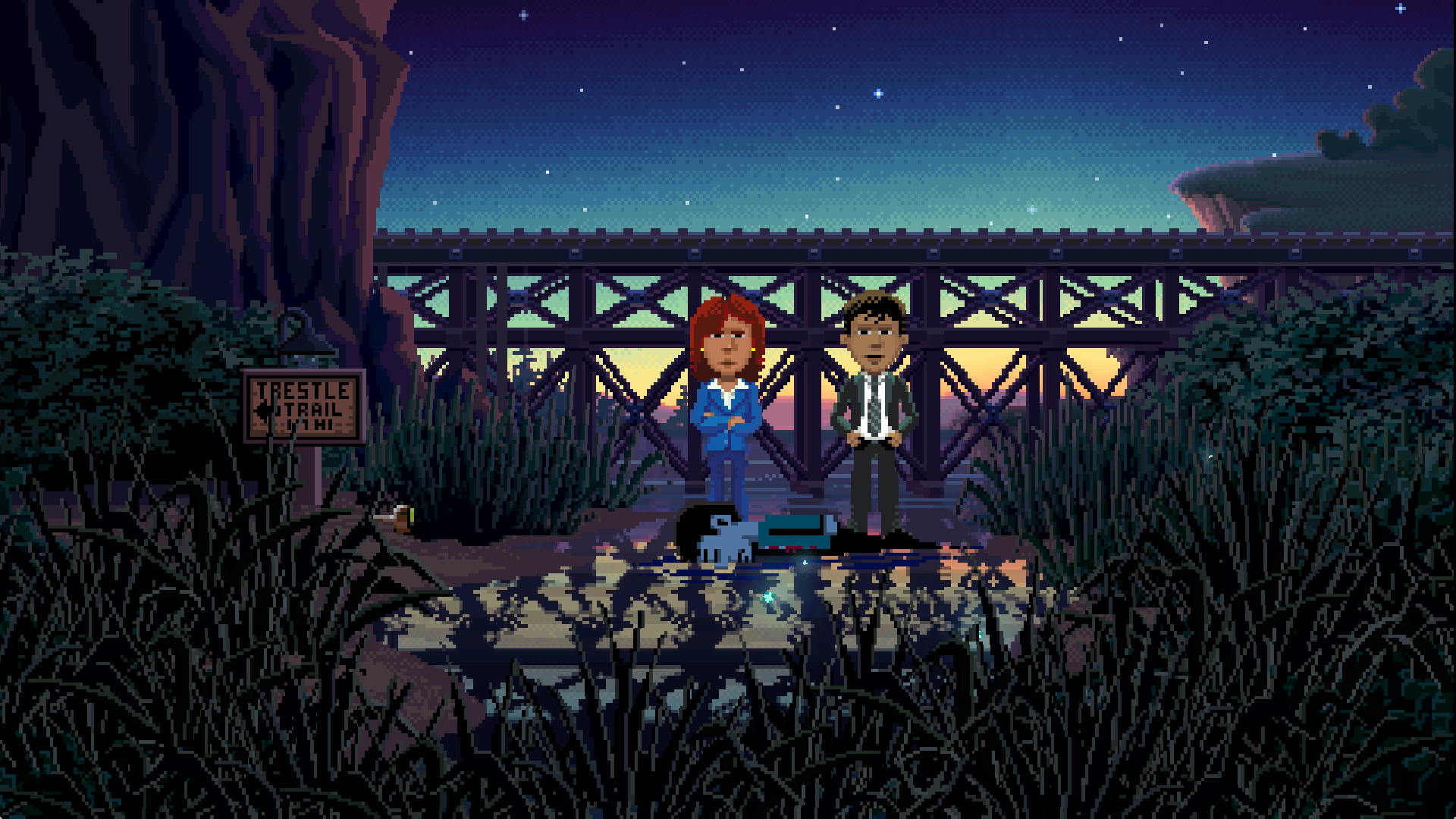

It starts, as these things often do, with a body. A man is lying face-down in the mud under a bridge, and FBI agents Angela Ray and Antonio Reyes are investigating. At the bottom of the screen is a classic nine-verb interface—the kind used in games like Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle—and I use it to examine the body. Ray notes that it’s already starting to pixelate; an example of the game’s dry self-referential humour. He’s approximately 40 years old, has been in the water for 24 hours, and I find a keycard for a hotel room in his pocket, but no ID. There’s also a small hole in the back of his head.

It isn’t much to go on, but my next step is walking to the nearby town of Thimbleweed Park to see if anyone knows anything about the victim or how he ended up dead under a railway trestle. I can switch freely between the two agents at any time and swap inventory items, which factors into some cleverly designed puzzles down the line. Ray is a sharp, sarcastic veteran agent who wishes she was anywhere else, and Reyes is her more easygoing counterpart. But subtle clues in their dialogue and journals suggest they’re hiding something—both from the player and each other. Just minutes in, the game’s already filled with intriguing mysteries I’m eager to solve.

I walk along the highway towards the town. On the way I meet two sisters dressed as pigeons, babbling about how “the signals are strong tonight.” Creeped out, Ray wonders if she should save the game, but the sisters reassure her that there’s no death or dead-ends in Thimbleweed Park, and that fail states like these actually make adventure games less enjoyable. See what I mean about it being self-referential? It takes a sledgehammer to the fourth wall at every opportunity, and it’s genuinely funny. “If this was a Sierra On-Line graphic adventure I’d probably be dead by now.” Reyes says later.

Thimbleweed Park might have been nice once, but now the streets are lined with abandoned buildings. It’s a grim, dilapidated place, and as I pass the boarded-up remains of a LaserDisc store I get the feeling that time has left it behind. Like all good adventure games, there’s an enormous amount of dialogue, and I spend at least an hour walking around the town inspecting and using verbs on everything I can. I visit the diner, eat a hot dog, and vomit in the alley outside. I meet the pigeon sisters again, who are actually plumbers and trying desperately to repair a broken fire hydrant (yes, it's a puzzle). And I walk to the top of a hill and see a sweeping view of the county the town is in, which will be explorable in the finished game, but is sadly locked off in my demo build.

I’m impressed by how atmospheric the game is, particularly how neon signs, crackling fires, and street lamps cast appropriately coloured light over the pixelated characters. Foreground objects and parallax scrolling combine to give the world a nice sense of depth, and I love how the artists have used reflections, animated scenery, and the aforementioned lighting system to give the retro visuals a modern sparkle. It’s clearly an homage to the golden era of LucasArts adventures, but it doesn’t feel like a cynical throwback or lazy nostalgia grab. These are some very fine pixels indeed, and the use of light, shadow, and perspective in the backgrounds is beautifully done.

Ray and Reyes meet with the local sheriff, who has a peculiar habit of adding “a-reno” to the end of almost every word. Informing him that we’re here to solve a murder (or “murder-a-reno”), he introduces us to three supercomputers that will help us solve the case. This is the first big multi-part puzzle the game throws at you, but I won’t say any more for the sake of spoilers. Yet according to co-creator Ron Gilbert, the murder isn’t the most important thing in the game. “Thimbleweed Park (for better or worse) is a big game,” he wrote on the game’s development blog last year. “And it’s not only big, but it's a complex story that weaves around, pretending to be one thing, then veers off in an unexpected direction just when you think you've figured it out.”

So it seems like the dead body is really just a catalyst for a number of different stories, and I wouldn’t be surprised if its importance faded into the background as the story develops. Especially when you consider that the agents are only two of five very different playable characters, each with their own unique motivations and personalities. Among these is Ransome, a mean-spirited, foul-mouthed clown who’s cursed never to leave his circus or remove his make-up. Delores, a talented computer programmer who dreams of working for MmucasFlem (see what they did there?) as an adventure game designer. And Franklin, the ghost of a pillow salesman. It’s a curious ensemble, and I’m looking forward to seeing how their stories meet up.

There’s a lot more I could say about Thimbleweed Park, but I’m wary of spoiling too much before its release ("soon" says Gilbert). From what I’ve played so far, it’s a funny, charming, well-written, and well-designed point-and-click adventure with heaps of personality. The art is gorgeous, the characters are interesting, and the mysteries are compelling. If it can keep this level of quality up for the duration of the game, however long it is, it could be something very special indeed. And as an adventure game fan, the very fact that Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick are making another one is worth celebrating. I don’t know what secrets I’ll uncover in Thimbleweed Park, but as the game’s sinister tagline states, in a town like this, a dead body is the least of your problems.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

If it’s set in space, Andy will probably write about it. He loves sci-fi, adventure games, taking screenshots, Twin Peaks, weird sims, Alien: Isolation, and anything with a good story.

Most Popular