Time Extend: The Stanley Parable

What it means to play a game about games.

This article was originally published in issue 306 of Edge. You can subscribe in print or digital by clicking here.

This is the story of a man named Stanley. It’s also the story of a player named you, and two game developers named Davey Wreden and William Pugh. It’s at once a meditation on choice, freedom and authority, on what videogames are, and on the relationship between developer and player. And it’s extremely funny. In fact, The Stanley Parable is one of the funniest videogames you can play, bearing the weight of its themes with absurdist lightness.

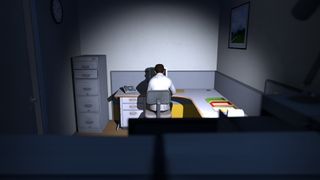

Stanley has started another day at work, pushing buttons on his keyboard as he always does—only today is different. No one is in the office. So he goes to the meeting room to see if his colleagues are there; they are not. He goes up to his boss’ office and it’s empty, too. But he manages to open a hidden door, which leads to him discovering the terrible secret behind his workplace. Stanley knows his purpose now, and destroys the facility that’s been governing his life, allowing him to escape into the real world.

If you do what you’re told in The Stanley Parable, you experience a story that you’ve played hundreds of times before: you’re on a hero’s journey, the nobody who becomes the somebody, the star of a world generated just for you. On a planet of 7.5 billion other people, you get a fleeting sense of feeling special. But in The Stanley Parable, the credits don’t roll when victory comes. The view returns to Stanley’s dingy office and the Narrator, in his perfectly modulated, BBC-announcer voice, once again says, “All of his co-workers were gone. What could it mean?”

So starts an eternal loop, a Garden Of Forking Paths, where you’ll choose your own path through Stanley’s winding office. Choose this corridor or that door; submit to or disobey directions; make this choice or that one, taking wildly different plotlines, each resulting in one of 19 possible endings. Whichever way you go, you’ll always be accompanied by the Narrator.

Eventually he starts to fantasise that you, the player, has died and will be replaced by someone else.

Voiced by Kevan Brighting, the Narrator is the focal point of The Stanley Parable, a constant throughout the surreal, surprising, disturbing and confusing events that you’ll set into action. Though Stanley’s office feels distinctly American, the Narrator is resolutely British, commenting on all you do with the authoritative tone of a documentary voiceover. He lends gravitas to Stanley’s mundane situation, a presence that you’re initially inclined to obey, or at least to take seriously. But as you begin to defy him, he starts to become a character, turning from talking about Stanley in the thirdperson to addressing him directly, becoming by turns prideful, injured, sneering, domineering, wheedling, chummy, recriminating, angry, callous.

The Narrator is, after all, not only the antagonist of The Stanley Parable but also the architect of its nightmarish maze of choices. The different stories you follow are all his, and your decision to follow them or not will delight or enrage him. The Narrator and Stanley are inextricably tied together, each unable to exist without the other. Take the Z ending, where the Narrator is trying to get you to remain in a room filled with a starfield and light patterns. “Don’t you see that it’s killing us, Stanley? I just... I want it to stop. I would—we would both be so much happier if we just… stopped,” he says. “If we just stay right here, right in this moment, with this place… Stanley, I think I feel… happy. I actually feel happy."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

But you can’t stay there. Well, you technically can, but you’re playing this game to be able to do something, and so you walk out, finding a series of stairs that lead up to a point you can throw yourself off. “Oh, no! Stay away from those stairs! If you hurt yourself, if you die, the game will reset! We’ll lose all of this!” the Narrator exclaims. You’ll survive the first fall, but presented with little else to do other than stand passively under the starfield, you’ll try it again. “My god, is this really how much you dislike my game?” he says. “I just wanted us to get along, but I guess that was too much to ask.” On the third attempt you finally die, and the game begins anew.

The Narrator is many things, from motivator to exposition-dealer, but most of all, he’s a representation of The Stanley Parable’s developers—or, at least, their relationship with players. His mood swings are an expression of the strain that lies between designers’ intentions and players’ free will, the way that narrative-driven games are designed around second-guessing the ways in which players will do the wrong thing or go the wrong way, whether intentionally or because they weren’t paying attention. He frets when the player breaks sequence and sees areas he hasn’t built, over plotting that doesn’t make dramatic sense, and over the game itself: would it be more popular if it was Minecraft or Portal 2?

Sometimes the Narrator conflates Stanley and you, the player, talking to both at once. Near Stanley’s office is a closed door with a sign reading ‘Broom Closet’. Almost every door is either closed or controlled by the game design, but if you should try it, this one will open. “Stanley stepped into the broom closet, but there was nothing here, so he turned around and got back on track,” says the Narrator. Stay in there, and he tries again: “There was nothing here. No choice to make, no path to follow, just an empty broom closet. No reason to still be here.” If you persist, the Narrator becomes increasingly frustrated and begins to mock the idea of you bragging to your friends about getting the “broom closet ending” and sneers at Stanley for only getting his job through family connections. Eventually he starts to fantasise that you, the player, has died and will be replaced by someone else who’s filled in on “the history of narrative tropes in videogaming”.

Having the game respond so richly to your action (or, here, inaction), feels greatly rewarding. If you reenter the cupboard on another playthrough, the Narrator will resolve not to react, knowing it’d only encourage you. And then, on the next playthrough, you’ll see the door is boarded up so you can no longer get inside. The Stanley Parable knows how some of the greatest rewards in videogames come from noticing details you weren’t pointed towards, like the scribblings on a whiteboard in a meeting room or the display on a monitor, and that there’s magic in having a game respond when you do something you think wasn’t expected. So when the Narrator spends some three minutes remarking on you standing in a cupboard you had the notion to enter, or reacts when you have the wild idea of trying to jump off a platform on to a gantry, it’s like a spark has jumped between you and the game, a reward beyond an XP bar going up for doing what you were told.

The Stanley Parable began life as a mod for Half-Life 2. Davey Wreden released it in 2011, three months after the debut of Portal 2, and both games share a thematic tension between the creator and player. The mod lacks the 2013 full release’s ‘office-real’ visual style, since it uses Half-Life 2 art assets, but it features the same structure and Kevan Brighting’s exemplary voice work, and it has six endings. After completing the commercial release of The Stanley Parable, which is also built in Source, Wreden went on to make the rather more affecting The Beginner’s Guide, which continues to explore the relationship between game creator, game and player. Pugh has also continued to make narrative games with his studio, Crows Crows Crows, pursuing a purer line in comedy.

It’s much quieter than the Narrator, but it’s the level design that’s making these moments really work, nudging your attention towards them while making them feel like secrets. Another dimension of The Stanley Parable’s grand joke about videogames is that under all of its subversion it’s very strictly controlled, funnelling you into rat runs that only let you move one way. Doors open and close at the level’s whim and most of the choices you’re presented with are binary, letting you go one way or the other and closing off the entrance after you go through. Its first moment of choice is a masterclass in spatial and narrative design. Beginning at Stanley’s desk, you make a few turns through the bland and deserted office and reach a room with two open doors opposite its entrance.

“When Stanley came to a set of two open doors, he entered the door on his left,” says the Narrator, and you immediately begin to appreciate what this game might be. Go left and the Narrator continues his story, leaving you wondering what would’ve happened had you gone right. Go right and he says, “This was not the correct way to the meeting room, and Stanley knew it perfectly well. Perhaps he wanted to stop by the employee lounge first, just to admire it.” And we’re complicit in the ruse, knowing the game’s primed to respond to every choice we make.

“The pacing of this opening section was important to get right—this corridor has been moved and altered to make sure the player reaches the two doors in a good time,” says a placard in a museum that lies down one of the game’s routes. This place is a literal record of the game’s development, exhibiting level plans, 3D assets and trailers in monumental white halls. It’s a moment in which the circle between game, developer and player is fully completed, and then, once we’ve toured all of its galleries, we’re left with no other option than to allow ourselves to be swept back into the office and let the cycle move on.

The Stanley Parable rests on this tension: of how narrative-based videogames can’t proceed without our input, and how they struggle to make this input meaningful. When you have too much choice, no decision has any particular value, and yet when your path is entirely preordained there’s no real consequence to your involvement. Playing games is so often a contradiction: in picking up the controller we want to submerge ourselves in the world of a game designer, and yet we constantly wish to break free of the decisions they make for us. Like that of the Narrator and Stanley, it can be an abusive relationship, but in it can also lie the reason we play—those sparks of connection where a game acknowledges our individual presence. “I’m not your enemy, really, I’m not,” says the Narrator. “I realise that investing your trust in someone else can be difficult. However, the fact is that the story has been about nothing but you all this time.”

Most Popular