These players loved their WoW servers so much, they bought the old hardware

Blizzard auctioned off retired hardware, and some players are still trying to obtain their own special piece of WoW.

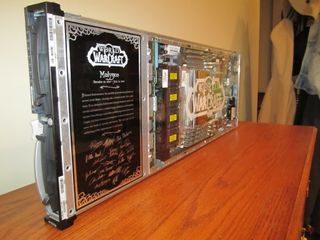

The server blades are delivered to your door in a clear glass coffin. There’s nothing surprising about how they look—streaks of electric-green circuit board, blocks of RAM, a sturdy power filter that worked tirelessly through nights and weekends to project Azeroth to thousands of PCs across the country. A silent, ivory World of Warcraft logo is embossed across the top, and silver signatures of the game’s founding fathers run across an epitaph along the side. Above them you’ll see the server name—which are all appropriated from crucial characters in Warcraft lore—and a short elegy penned by the Blizzard braintrust.

“To us, this server blade is more than just hardware: within the circuits and hard drive, a world of magic, adventure, and friendship thrived. From fishing in quiet lakes to defeating Arthas in Icecrown Citadel, this blade was home to thousands of immersive experiences,” it reads. “We thank you for the safekeeping of this important part of our history.”

Electronic realms

World of Warcraft is comprised of hundreds of different servers (or “realms,” as designated by the in-game flavor text.) Each of them hosts a small subdivision of the game’s 10 million players. Effectively, they serve as World of Warcraft’s neighborhoods—every realm has a unique economy and emotional tenor, and players embrace them like a University student embraces their school colors. In 2012, eight years after Warcraft’s 2004 release date, some of the server tech was getting pretty old. It’s the predictable challenge of hosting an extremely popular MMO—retrofitting and modernization is necessary once your video game enters its middle-school years—and Blizzard found themselves sitting on a stockpile of decommissioned server blades.

But instead of ingloriously disposing of them at a tech recycling service, the company decided to auction them off for the benefit of St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital. Blizzard smartly realized that despite their unglamorous appearance, those blades touched a soft spot in the Warcraft community. In total, about 300 blades were encased in those tombs and made available to the public.

Knowing that I am holding a very important part of what made that type of experience possible for many thousands of people does have some sort of gravity.

Since then, the prodigal server blades have become a white whale for World of Warcraft collectors. The secondary market is scarce and brutal, with prices routinely crossing the four-figure mark. That’s where Chris, 31, turned after coming up short during the initial auction.

“I was bidding on four at the same time for a couple of different realms but I was at work around the time it was ending. I couldn't just sit there refreshing the pages non-stop,” he says. After that failure, Chris would occasionally punch a request into eBay, hoping to track down a specimen that wasn’t “ridiculously expensive.” Eventually he found a decent bargain after propositioning someone who posted pictures of their blade (from the U.S. server Blackhand) on the World of Warcraft subreddit. They agreed on a price, and finally Chris was delivered his pièce de résistance.

Homecoming

He mounted that blade in the prime position of the “WoW Shrine” in his office. It sits adjacent to the prowling Illidan sculpture, behind the foreboding Arthas statue, and above a glass cabinet housing the Collector’s Editions of every World of Warcraft expansion. (He’s still missing a Collector’s Edition of the original game, which are notoriously rare.)

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Compared to the rest of his collection, the blade can look a little quaint. It is, after all, just a bulky piece of exposed tech, identical to the thousands of hard drives whirring away in Blizzard server bays across the globe. Its eyes do not glow green like Illidan's, it doesn’t come with the opulent panache and custom mousepad of the $99 Legion box. But that’s the point. Chris has spent the last 12 years of his life exploring World of Warcraft, and there’s something about the server blade that feels more real and more crucial than every other piece of memorabilia Blizzard has put up for sale.

“Some of my most memorable moments in my life was playing World of Warcraft with my friends. From discovering the game at the start to downing bosses and getting our server firsts and feeling that rush of excitement. I have built life-long real life friends that started out as virtual relationships through this game,” says Chris. “Knowing that I am holding a very important part of what made that type of experience possible for many thousands of people does have some sort of gravity.“

I just wanted to own a part of World of Warcraft.

It was the same itch for Alex, a 23-year-old in the U.K. who told me he was too young and too broke to afford a server blade when they first hit auction. He’s been active in World of Warcraft all throughout his teenage years, into college, and beyond. He still plays today, but with a full-time job he can’t double-down on those endless juvenile weekend nights like he could back in grade school. That’s fine (and probably for the best), but whenever Alex and Warcraft take some time apart, he always finds himself coming back in search of that same sense of wonder. It’s something he never expects to disappear completely.

“I think I am the person I am today because of that game,” he says. “I spent so much time playing [Warcraft.] It’s helped my personal and social growth. You do feel like it’s part of your life in another world, instead of like any other game where you just finish it and that’s the end.”

He got a good deal on a blade from the European Grim Batol realm, which is now displayed proudly in his living room. Out of all the other pieces of Warcraft swag that populates his place, the blade is the one thing he can translate to his friends who have never trekked through Azeroth. “The other stuff is just nonsense to them, but having something that actually runs the game? [They think] that’s cool,” says Alex. “I put it up on Instagram, which is something I don’t do with other game stuff.”

“I just wanted to own a part of World of Warcraft,” he continues. “Because the game has been such a big part of my life for such a long time, it just makes me feel like I’m a part of something.”

Priceless

A modern, high-end server blade will run you about $15,000.

A modern, high-end server blade will run you about $15,000. Right now, on eBay, you can bid on a replica of Frostmourne (the runeblade carried by the infamous Lich King) for $1,200. Both of those things have an inherent utilitarian purpose or an aesthetic value—the server will let you power a video game, the sword is imbued with the sort of limited-run nerdy elegance that divorces thousands of super-fans from their money at Comic-Cons every year. But Chris tells me the financial worth of a retired Warcraft server blade is extremely personal, and more than anything else, it depends on the buyer’s relationship with the realm in question.

“It's kind of like anything in the world of collectors: It's worth exactly what someone is willing to pay for it,” he says. “It's very likely that someone out there who might still play WoW on Blackhand to this day happens to be very successful in their line of work would be willing to pay thousands of dollars for [my] server.”

Chris isn’t immune to that instinct. He’s had characters on Blackhand, but he doesn’t consider it his ancestral server. The four other blades he bid on during the initial auction tug at his heartstrings more. If someday one of those blades enters the market, he’s says he’d be willing to “spend a pretty penny.” There is a beauty in looking at a circuit board and seeing yourself in the reflection.

Personal history

That’s the thing about World of Warcraft: deep down, it’s a melancholy game. You and 20 friends are toppling the thrones of the greatest villains in the canon. That camaraderie is irreplaceable. You are the heroes you think you are. But then things start to change. A friend has a kid and can’t free up weeknight raiding hours, your guild leader gets burned out and quits for his own sanity. The faces and names that helped you fall in love with Azeroth slowly go missing, and you can’t find the fire to log on anymore.

Suddenly you feel kinda silly that some of your most cherished memories were spent on the pinnacle of Blackwing Lair, and you don’t fully understand why you’re missing it so much.

But that mournfulness can also be extremely relatable. It’s something Blizzard understands very deeply. Every server blade they sold comes with an inscription spelling out its birth and death date. “Grim Batol, May 8th 2005—August 4th, 2010.” The company treats their multiplayer tech as a living, breathing thing, because it was occupied by living, breathing people. Anyone who’s spent any significant time in World of Warcraft understands that same loss, and those bonds can be just as strong as anything you forged in-game.

Hopefully I can find my own realm someday.

Alex, like Chris, keeps an eye out for other server blades that are closer to his personal life. His white whale? Defias Brotherhood, the same realm where he started his journey. Alex adores his Grim Batol blade, but he’s also extremely aware that he’s holding onto something that’s priceless to the right person. If he ever meets them, he might be willing to give it up.

“I wanna have a server blade, but I can understand if Grim Batol meant a lot to someone—just being the fan of the game that I am, it would be wrong of me to hold onto it if they really wanted it,” he says. “It means a lot to me, but it’ll mean more to them. Hopefully I can find my own realm someday.”

Perhaps that’s the true brotherhood between gamers. Most people can’t understand the emotional attachment to an outdated server blade, but if you were in the trenches, it makes all the sense in the world.

Chris and Alex are ritualizing one of the best parts of their lives. They’ve brought World of Warcraft into reality and framed it on their wall. They’re ordaining their virtual adventures, right alongside their wedding photos. It’s an empty piece of technology, and it’s also proof that it wasn’t just a dream.

Luke Winkie is a freelance journalist and contributor to many publications, including PC Gamer, The New York Times, Gawker, Slate, and Mel Magazine. In between bouts of writing about Hearthstone, World of Warcraft and Twitch culture here on PC Gamer, Luke also publishes the newsletter On Posting. As a self-described "chronic poster," Luke has "spent hours deep-scrolling through surreptitious Likes tabs to uncover the root of intra-publication beef and broken down quote-tweet animosity like it’s Super Bowl tape." When he graduated from journalism school, he had no idea how bad it was going to get.

Most Popular