Our Verdict

Witty interactive storytelling thats best with a group and weakens significantly after a few brief playthroughs.

PC Gamer's got your back

She drank for six weeks straight. That is, except for the week she inexplicably spent fighting crime in the slums. That was weird. But any other time you'd have found her in the tavern, throwing back pints and spilling conversation all over the place.

He spent a quieter six weeks: studying magic, mixing potions, mediating in the gardens to hone his mind. She stumbled into a dart tournament, broke up a brawl, and shooed away a tone deaf bard. He fought a rogue goo monster, witnessed a miracle, and turned a frog into a prince.

On the seventh week, the world ended. And that's one playthrough of The Yawhg , excluding the epilogue: 10 or so minutes of decision making with two to four characters (controlled locally, and best with other players). It's a text-based interactive short story about flawed characters coping with disaster, meant to be played again and again, but differently.

The static art complements the text well, cute but not saccharine and with enough sadness to pair well with the often tragic stories The Yawhg generates. Ryan Roth and Halina Heron's superb acoustic soundtrack best expresses the tone: foreboding and melancholic, but laced with optimism and levity. The Yawhg really is a sad game, but sad in the sort of way you have to laugh along with.

The end is nigh

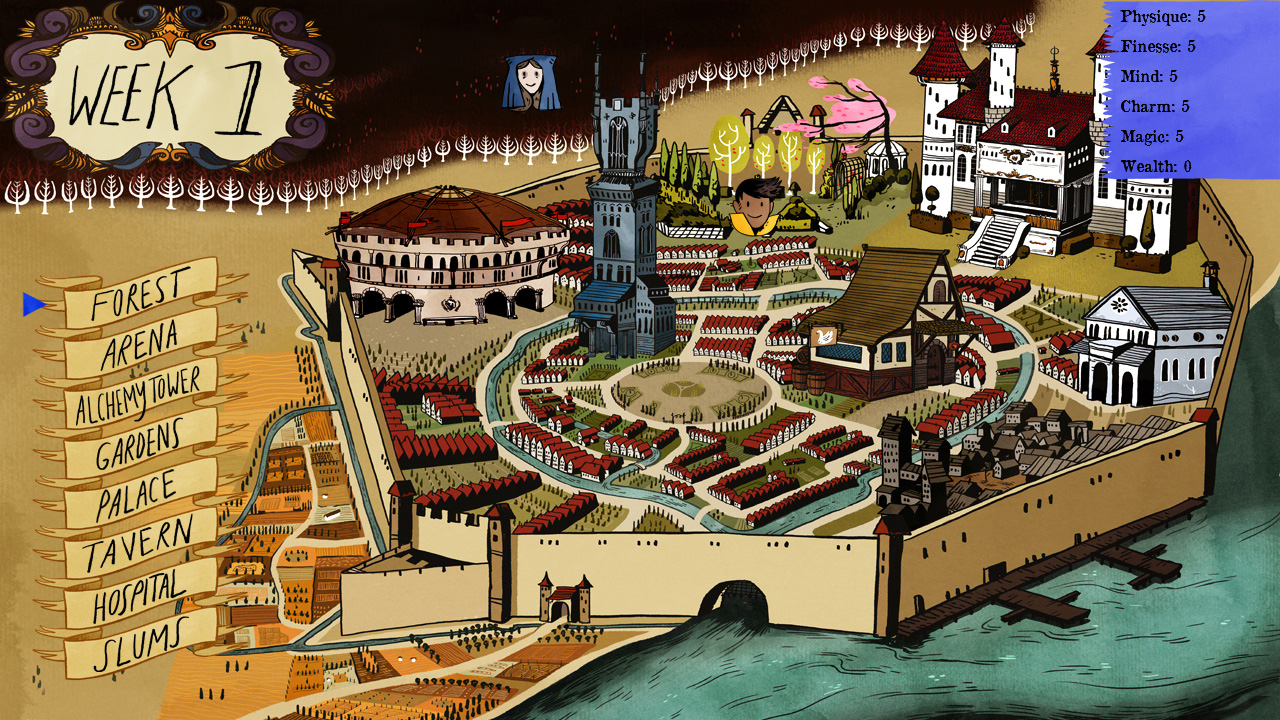

One game spans six weeks, which translates into six turns for each character. Each turn begins with deciding what to spend the week doing. Clean up the hospital? Attend a ball at the palace? Go hunting in the woods? Drink? Each activity increases one or more character traits—drinking at the tavern, for example, boosts Charm and Physique.

After choosing an activity, a randomized event with a binary decision elaborates on the story and offers the opportunity for another stat boost—or loss, if the character fails. While drinking, for instance, a brawl might break out. With enough Charm, I can settle the patrons back into their seats, or I can jump into the fray to test my Physique.

The events are often intentional fantasy clichés—a slime monster, a dark ritual in the woods—but with a modern sensibility and humor. In one storyline, I ran into an ex-lover with her new boyfriend and chose to be filled with terrible jealousy, decreasing my Charm but increasing my Physique as I consumed my aggression with exercise. Other events can destroy parts of the town, making them inaccessible to all players, and some can lead to follow-up events: I later ran into my ex's new man again and punched him in the face.

Whatever happens in that six weeks, it always ends with The Yawhg—a vicious storm that destroys the town. Everything is lost, but hope remains: each player now assigns her character a role in the rebuilding. My drunk was full of charisma, so I chose her to lead, while my conjurer would summon supplies for the builders. Their stats determine their success, and the story machine spins up to generate an epilogue for the town and players.

It's possible to earn a bright future for the town, but in this case, we were defeated. My drunk, after witnessing The Yawhg's horrors (including a pack of schoolchildren eating the corpse of their teacher), lost herself again at the bottom of a bottle. The conjurer fared only slightly better. He obsessively mediated until he crossed into the astral plane, which is the same as our world only everyone's eyes are a little smaller—and there is no return.

Time is a flat circle

Designer Emily Carroll's writing is funny, succinct, and confident. Her voice is amusingly dispassionate, putting it on the players to feel empathy or not when their characters reach their often horrific fates. There are over 50 possible epilogues, and many that I've seen are as cruel as an Edward Gorey poem (“K is for Kate who was struck with an axe") and narrated with the same matter-of-fact detachment.

And if the endings aren't tragic, many are at least melancholy, twisting a seemingly positive story into an unhappy life: a famous wizard who can conjure everything but a love potion, a successful bar owner who homogenizes the industry through franchising. There are happy endings, but I prefer the tragedy that comes from unbalanced playthroughs. When multiple players have projected their personalities onto their characters, there's a lot of fun in stepping through the epilogues line by line, anticipating each one as we discover if anyone gets a happy ending or if we're all left mugged and bleeding on a pile of rubble.

For that reason, The Yawhg is a great way to have a few morose laughs with my girlfriend, or with a small game night group. Very quickly, though, it starts repeating itself. With no imagination of its own, The Yawhg can't offer outcomes or choices Carroll didn't write. There are plenty of possible epilogues, but after two to three playthroughs the randomized events become familiar. After around five times through, I was experimenting with intentional combinations of actions to get a look at alternate endings—rushing through to see my tragic fate. I was tinkering with the story machine instead of playing along, and The Yawhg lost its suspension of disbelief and a lot of its value.

It's like a casual tabletop roleplaying game with a dungeon master who isn't prepared for more than a few rounds. I imagine The Yawhg that way, as a game box tucked into my bookshelf. I might take it out for friends who haven't played it yet, and we'll laugh as someone rolls a perfect round of drunk darts or deals with an unstable potion by throwing it into the town water supply. And after a few rounds we'll shelve it, happy to have played, but noting that there's no point in going on if we keep dealing the same events.

In a couple months the alluring box art might be noticed by a new group, and we'll play another few rounds so I can enjoy their discovery and a few surprises I missed or forgot about. And we'll quickly shelve it again with the same conversation. The Yawhg is a salvo of imagination that depletes its ammunition quickly, best enjoyed in brief sessions, weeks apart, with new friends and a little forgetfulness.

Witty interactive storytelling thats best with a group and weakens significantly after a few brief playthroughs.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.