"I call myself an accidental entrepreneur," says Larry Holland. That's Holland's casual way of saying he never really planned on designing some of the most popular PC games of the '80s and '90s, or aspired to meet Steven Spielberg and learn the director was a fan. His childhood dream, starting around fifth grade, was to become an archaeologist.

"I wanted to explore the world and find lost civilizations and make sure they weren't lost to time," he says. Through high school and college, Holland studied Latin, Greek, human evolution, prehistoric archaeology, anthropology. After graduating, he spent a year working and saving up for a trip around the globe. He toured Kenya and Tanzania and visited ancient sites such as the Olduvai Gorge—"sort of like the cradle of man."

None of that seemed like an obvious path toward making TIE Fighter, a groundbreaking flight sim that would have a dramatic impact on the Star Wars universe, and certainly one of the greatest Star Wars games of all time. But it's funny how these things work out.

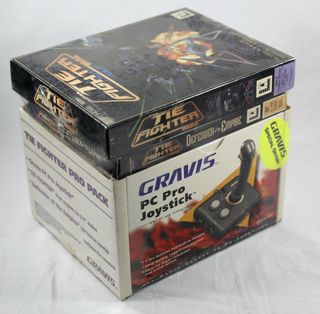

The DOS version of TIE Fighter hit stores in July of 1994, about 17 months after X-Wing, the first game in the series. It was immediately noteworthy for being the first-ever video game to let players assume the role of a rank-and-file TIE pilot in the Imperial Starfleet. For the first time, a Star Wars game let you be the bad guy. "It actually made you feel proud to fly a ship for the Empire," Darth Maul voice actor Sam Witwer told G4 back in 2012. "You actually have that twisted point of view, which is really fun."

Critics thought so, too. PC Gamer magazine's writers named it the year's best action game, and it probably only lost out on the overall game of the year award for one reason: id Software's Doom. But the mag did declare TIE Fighter "the best space-combat simulation ever created," and more than 25 years later, few Star Wars fans would argue otherwise.

Here's the story of how it came to be.

A time machine

In 1981, Larry Holland wound up in the Bay Area, hoping to pursue a doctorate at UC Berkeley while working a job on the side. "At the time, I was in kind of an old-style rooming house in San Francisco, and one of my roommates there actually had an Atari 800. That's when I got very accidentally exposed to the current state of computers and computer software and computer games." Holland had dabbled in programming in high school in the mid-seventies, but the tech world had already entered a new age. Curious, he went out and bought a Commodore 64 and began teaching himself the assembly language.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

What really intrigued me was doing simulation games, or games that had some recreation of the real world

Larry Holland

Inspired by the golden age of the arcades, he started programming games of his own and eventually found work "in the early cartridge-based C64 and VIC-20 industry." The pivot from archaeology and anthropology to suddenly making computer games seemed like a total right turn, he admits. But in hindsight he understands the connection.

"What really intrigued me was doing simulation games, or games that had some recreation of the real world," Holland says. "My first game along those lines was called Project: Space Station, which I did in 1985. That was about the shuttle program of that era, and the early imaginings of the International Space Station that, years later, actually happened. But the game was about the construction, and doing some simulation of the experiments on board." Once Project: Space Station was out the door, Holland found himself working in a small skunkworks lab made up of about 10 employees and contractors. He'd been brought in as an independent contractor to write the Apple II port of a war sim called PHM Pegasus. The team developing Pegasus for the Commodore 64 was called Lucasfilm Games, and its office was located inside Marin County's Skywalker Ranch, the famous Victorian-style house owned by Star Wars creator George Lucas. That was his first step on the road to TIE Fighter.

"When I started working with Lucasfilm Games, I knew them, of course, because of George Lucas," Holland says, "but I didn't join them because they were the Star Wars company. I wanted to work with them because they were doing some cutting-edge game technology; the mission for Lucasfilm Games was that they weren't even supposed to think about making Star Wars games." Various outside entities, like Atari and Broderbund, had held the license for video games set in the galaxy far, far away since '82.

By March of 1988, Holland had completed work on a second Lucas game called Strike Fleet. He'd also developed a fascination with military history—and a bold new vision of his own.

"I did some technology research about how to pull off some more realistic-looking, but not yet 3D-oriented, graphics, and I pitched them a game called Air Wing," he says. "That was a one-page pitch, typed out on a real typewriter, with, I think, an accompanying schedule and a milestone budget attached. What was different about this was it was going to be for the PC. Our previous games had been on the Commodore 64 or the Apple II, and this was right in the era where the PC market became something. People were caring about it."

The Air Wing pitch resulted in not one but three projects, spanning from '88 to '92: Battlehawks 1942, Their Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain, and Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe. With Holland now acting as project leader, Battlehawks was the birth of both the technology and design philosophy that eventually shaped his work in the Star Wars universe. He wanted to do in games what his archaeology background had taught him: Unearth whatever pieces remain of the past, examine them from every angle, and try to "recreate what life was like." He came to realize that every pilot who'd ever fought or died for their country was, in a grand mythological sense, a hero among their own people, having donned a uniform and pledged to fight in defense of a cause.

"When I was making these World War II sims, really what I was trying to do is create a time machine," Holland says. "I always called it an air-combat game as opposed to a simulation, meaning that it wasn't about recreating all of the aerodynamics and the gadgetry or gauges of a particular plane, but more to create the environment of air combat, and the feel and the emotion and the action."

To achieve this, he devoured countless books, diagrams, documents, films, and even gun-camera footage captured by World War II fighter pilots—the very same footage George Lucas famously used to devise the dogfighting sequences in 1977's Star Wars. Holland also interviewed veterans, including Richard H. Best, a US Navy dive-bomber pilot who fought at the Battle of Midway. (Best later wrote a preface to the manual for Battlehawks 1942.)

"Star Wars was not in the conversation, really, until the middle of my World War II series—1990 and '91," Holland remembers. "Steve Arnold, who was head of the games division, got the rights to do Star Wars games back from the licensing group, and so Broderbund no longer had it." Brian Moriarty (famous for the 1990 graphic adventure Loom), with whom Holland shared an office, issued him a challenge: "If you don't make an X-wing game, I will."

That was, he says, "the first time where I understood that it was a possibility."

Starfighters

I had built up enough trust that I didn't have to do a big dog-and-pony show, a big pitch, to convince them that I could actually build an X-Wing game

Larry Holland

In 1991, Holland earned a reputation for being "this crazy programmer who haunted the halls of what was called Z Building, the complex right across the parking lot from ILM." By then Lucasfilm Games had become LucasArts and outgrown its home at the ranch. His ambitious next game, Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe, had taken on a kitchen-sink quality.

You could play as the US Air Force or the German Luftwaffe. It had a campaign and a custom mission builder. For the last six months of the project, Holland rarely bothered making the drive home. He simply lived and slept in his office at LucasArts, where he was still a third-party contractor, as much as possible. Some nights the security guard would shine a flashlight into his room, waking him at four a.m. on the office couch.

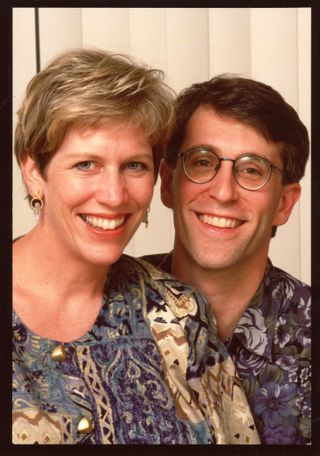

After Luftwaffe hit shelves, Holland began developing a series of expansion disks that added additional planes. Robin Parker, a new product marketing manager for LucasArts, was assigned to help Larry's team package and sell the add-ons. This was Parker's first foray into the games industry, but she'd come from the chaotic world of ad agencies, selling boutique mountain bikes. The transition was an easy one.

"I went over to Lucas knowing that the companies were quite similar, in that they were niche products for male audiences," she says. "But the people who worked at Lucas were a really different breed... They were way more interested in Dungeons & Dragons; they were gamers. There were some business people in there, but there were just some really passionate game-oriented creatives." Before long, she and Larry hit it off and began dating.

"We got married, actually, right after X-Wing," Larry says. "Then she was part of building the legit company during TIE Fighter after we got married. And we had kids; kids started coming right after TIE Fighter, so there's a lot going on in my life that changed from the World War II series, ultimately, to X-Wing and to TIE Fighter."

A few months into their relationship, in late '91, Larry's team started making X-Wing. Robin, meanwhile, was tasked with marketing the point-and-click adventure game Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. Given the immense machine that controls the Star Wars license today, it's amazing how easily Holland got the green light.

"I think that I had built up enough trust and legitimacy that I didn't have to do a big dog-and-pony show, a big pitch, or a big design document ahead of time to convince them that Star Wars was going to be in safe hands—that I could actually build an X-wing game," Larry reflects. "I think there was a very short design doc. It might've been a couple of pages, which would've taken some of the formula of my previous games and applied it to Star Wars."

X-Wing was an innovative, first-person space-combat sim in which players took on the role of Keyan Farlander, a pilot for the Rebel Alliance. While it lacked the branching story structure of the similar Wing Commander series, it found depth and complexity in both its puzzle-like mission design and clever energy-management system. As Computer Gaming World put it in their June 1993 review, "Each ship is somewhat like a flying battery that supplies power at a slow but steady rate. This power can be directed to the engines, the lasers, or to the shields. Diverting power to one area reduces the amount available to the others."

To master X-Wing is to master this system. The game boasted LucasArts' patented iMUSE audio system, which could smoothly change music tracks to match the action, and 3D polygonal graphics—rudimentary today but impressive for the time. X-Wing's manual highly recommended an extra 512 kilobytes of expanded memory, which tells you something about the tech it was running on. Most importantly, though, it delivered a particular fantasy: Flying an X-wing into battle against the Empire's planet-killing superweapon, the Death Star.

"Every game that I had done since Battlehawks was evolving the engine without totally throwing it out and doing something new," Larry says. "There was always a foundation to build on. The graphics engine was rebuilt or replaced, and went from only bitmaps to bitmaps hybridized with 3D to X-Wing, which became 3D. Whole other sets of systems were already fleshed out and evolved, so that really reduced the risk."

There were some really creative people there. There were people who loved making costumes and dressing up as animals—furries. There were people playing games of all kinds all the time

Robin Holland

In addition to Holland, X-Wing and TIE Fighter had only two other programmers: Peter Lincroft, who wrote the 3D "flight engine," and Ed Kilham, who was responsible for the cinematic engine that carried much of the narrative. Larry handled the AI programming for the games' mission builder.

Right away, based on the hard lessons he'd learned on Luftwaffe, Larry made a decision that shaped the entire X-Wing series: the first game would include only the Rebel Alliance's perspective. "I knew early on that I wanted to use the same dual perspective for the Star Wars material. But I didn't want to put it all in one game. That was crazy," he says. "This was going to be a game that had a lot more story in it, and more role-playing of an individual character—a Luke Skywalker type—as opposed to previous games that were more laboratories of history."

You can see Holland's "realistic" approach to making a Star Wars game even in X-Wing's manual, which is written as though you're a real rookie pilot joining the Rebellion. It describes one mode, called Historical Combat, as "recreations of actual encounters with Imperial Forces."

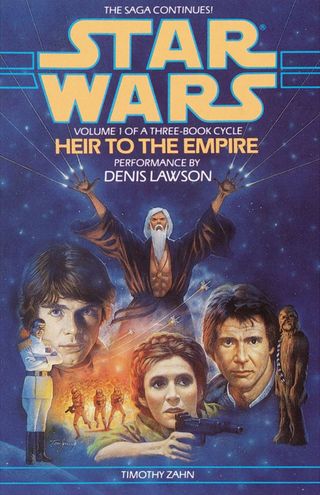

The late '80s and early '90s are often referred to by Star Wars fans as the "dark times." The made-for-TV Ewoks movies had come and gone, and Lucas's special-edition re-releases and prequel films were still a few years off. Timothy Zahn's "Thrawn trilogy," beginning with the 1991 novel Heir to the Empire, sparked a massive resurgence of interest in Star Wars—as did Dark Empire, the comic-book sequel from Dark Horse. X-Wing launched a few months ahead of Zahn's third Thrawn novel, The Last Command, and had the good fortune of being the first-ever Star Wars game published in-house by LucasArts. Previous Star Wars games—with the notable exception of the 1983 arcade game—were mostly mediocre movie tie-ins for the Atari 2600, Game Boy, NES, and other consoles.

X-Wing and especially TIE Fighter, which made heavy use of Zahn's Grand Admiral Thrawn character, arrived at an opportune time.

As Larry's team continued to grow, and testers from LucasArts began helping with the project, he moved the operation to a rental house on Redwood Road in Fairfax, California, a "yippie sixties throwback" of a town in Marin County, north of San Francisco. The neighborhood's narrow streets were soon overrun with cars belonging to X-Wing developers, and Larry realized it was a short-term solution, a stepping stone toward the business that would ultimately become, in 1995, Totally Games.

Robin describes a photograph taken of Larry's office at the Fairfax house: Him seated at his desk, three CRT monitors glowing simultaneously before him, pizza boxes and soda cans and potato-chip bags scattered around him. Here was a man who'd once lived and slept at LucasArts for half a year; Robin saw an opportunity, going into the TIE Fighter era, to bring a bit of work-life balance to the makeshift studio. She left her job at LucasArts in March of '93. "It was actually really fun. When I first started working with Larry, he's like, 'You know, you don't have to work. You could just go do whatever you want to do.' And I'm like, 'What, are you kidding me? I wouldn't ever see you.'"

"Totally Games was part of organizing into a formal company and actually hiring employees and profit sharing and naming the company and deciding on a logo and mission and all that sort of stuff. That really came about in and around TIE Fighter," Larry says. "It was part of this process of growing as games got more complex and richer. One of the things that was happening was the transition from floppy to CD."

3D computer graphics were improving by leaps and bounds in the '90s, which also meant an increase in costs and personnel. Battlehawks had cost Lucasfilm about $62,000, whereas X-Wing's budget was in the ballpark of half a million.

X-Wing arrived in February of 1993 and became a huge hit, selling 100,000 copies at launch. "While I occasionally cursed the game when replaying a tough mission for the umpteenth time, still, I must say that I enjoyed the experience tremendously," Computer Gaming World wrote at the time. "I wait with mind-clouding impatience for the forthcoming add-on disks and sequel." By December, the game had sold roughly half a million copies.

For Star Wars games, at least, the dark times were over.

A key part of the dynamic at Peregrine Software, as Holland's company was known prior to the incorporation of Totally Games in '95, was that, unlike most of his employees, Larry wasn't a Star Wars fan in the usual sense. He'd grown up reading science-fiction novels by Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Heinlein; his cultural touchstones were the Vietnam-era counterculture, Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the Apollo 11 moon landing. He was in college, doing an archaeological dig in southwest France, by the time Lucas's original Star Wars hit theaters.

"It gave me a little bit of a detached perspective that I think helped," he says, "because I had fanatics all around me."

"There were some really creative people there," Robin says. "There were people who loved making costumes and dressing up as animals—furries. There were people playing games of all kinds all the time. These people were really into games. And into Star Wars. We had Star Wars models everywhere; we had posters. We had an enormous and deep library of any kind of book you would need about space, about flight, about Star Wars. Certainly, we had all the Joseph Campbell stuff. It was just a fun workplace with a bunch of guys doing stuff that they were passionate about—hardly any women. I was one of the few."

While Robin acted as the fledgling studio's CFO, building the business from scratch and hiring on new talent when necessary—on top of managing the ongoing relationship with LucasArts—Larry had to ensure that TIE Fighter was more than just an X-Wing rehash from the enemy's viewpoint.

"You couldn't just stay the same, and you couldn't just give the other side of the story," Robin says. "That wasn't ever what it was about. It was about: How can we advance this experience? Whichever side we're working on, whatever story we're telling, how can we make this even more immersive? That's why we called the company Totally Games."

"X-Wing's sort of like the expected and obvious, and I think we executed it, for the time, pretty damn well," Larry says. "But by the time of TIE Fighter, we had a more robust system. Because, when it comes down to it, X-Wing was a really hard game. It was complex. It was a good story, with good motivation, but what you actually had to do in the missions—it was kind of hard to figure out. TIE Fighter had a lot more nuance and layers, and supported you as a player by giving you better tracking information about how you were doing, with the instrumentation and so forth."

Then he adds the crucial bit. "Of course, we just had a cooler story to tell."

Floppy disks and tin cans

In the '70s, George Lucas and his early collaborators at Industrial Light & Magic took the visual logic of World War II naval combat and moved it to outer space as they developed Star Wars' battle scenes. Similarly, Larry wanted to use real-world history to bring to life the worldview of an expendable pilot under the banner of the Galactic Empire.

Expanding on the successes of X-Wing, the sequel was novel for its Imperial viewpoint and because it dared to tell a rich story well outside the parameters of a typical movie tie-in. Like Zahn's novels, here was a game that introduced all-new characters, new starfighter designs, and explored the time period between The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. It had never been done! And, especially exciting for Star Wars diehards, TIE Fighter told yet another tale of the villainous Grand Admiral Thrawn, who had quickly become a fan favorite.

Holland describes his first time playing the game as though a TIE Fighter were an artifact you might find out in the world, restore, and take flight in

Where X-Wing more or less felt like an adaptation of the original Star Wars, TIE Fighter was a story all its own.

"TIE Fighter was our chance to do everything that we thought of but didn't get to do with X-Wing, from a function and an experience standpoint," Robin says. "Because I was so close to Larry, particularly, and the team—and new to the whole realm—what was really fascinating for me was to witness the creative process. And I know TIE Fighter was a real coup, because we were always playing with the good guys, and now we could take the point of view: Who was the good guy, really? That comes from Larry's background in anthropology, and wanting to see the different sides of things. I think it was an interesting move; it put something new into the Star Wars universe."

Another way TIE Fighter differs from X-Wing is in its branching, nonlinear structure. Along with a pair of mission designers, David Wessman and David Maxwell ("The two Daves," naturally), Larry arranged an overall narrative arc, a cast of characters, and the plot beats that needed to occur in each of the game's charming animated cinematics. Set in the aftermath of the Battle of Hoth, TIE Fighter shows the rebels scattering in search of a new base. Thrawn, meanwhile, hunts for an Admiral Zaarin, traitor to the Empire (one of the team's original characters), with appearances by the iconic Darth Vader and Emperor Palpatine at key moments throughout.

Scenes are rendered with a mix of altered stills from the Star Wars films, new digital art and animation, and in-engine 3D events. In a video interview shot just a few weeks before TIE Fighter was finished, Holland said one of the big challenges with the game was fitting it onto floppies, rather than a CD. "The quantity of interactive, animated cutscenes we'd like to add had to be limited. The amount of digitized voice, sound effects had to be scaled back so we could shoehorn it onto five disks."

"I would coordinate what the artists would do with the missions to make sure they all hooked together," Larry remembers. "The project leader basically did everything that wasn't straight development. As teams grew, then you had directors and producers and multiple levels of producers, but back then there was one guy who kept all the wheels turning together."

To fill the void left by Robin at LucasArts, the publisher's marketing director, Mary Bihr, recruited Barbara Gleason to handle the marketing for TIE Fighter. "Mary hired me on because she was planning a vacation the next day," Gleason recalls. "She was friends with my previous boss, and she sort of stole me away. I think she just wanted a warm body that kind of knew about video games."

During Gleason's first week on the job, Bihr made time to drop by and take her to lunch. The pair went to eat at Skywalker Ranch. "And I just about fainted going in there, because there was George, having lunch with John Singleton, the director of Boyz n the Hood. It was magical."

Gleason found TIE Fighter an exciting but daunting challenge. A year earlier, her boss had spent tens of thousands of dollars on X-Wing ads in magazines like Computer Gaming World and PC Gamer, and that first Star Wars dogfighting sim "shot to the top of the charts." But because of the sequel's unconventional viewpoint, Gleason felt she needed to get creative.

She wrote all the Imperial faux-propaganda copy for the back of the box. "Serve the Emperor!" she implored. "Pirates raid interstellar traders. Terrorists threaten the galaxy. Through their treachery on Yavin, the alliance of rebels and other criminals has threatened the very foundation of the Empire."

Gleason collaborated directly with the in-house art department to rework the box art—sometimes breaking from the established way of doing things. But people at Lucas were often thrilled to go beyond their normal responsibilities and help make something great. (The company could afford the best artists in the business, yet had a reputation for underpaying them because they were all so psyched to be working on Star Wars.)

"I think what really helped the game is that we were approached by Dodge, the car company," Gleason says. "I wasn't in much of a bargaining position; I didn't have a whole lot to give in return, other than they get to use Star Wars in their advertising. For the Dodge Neon, which was nothing like a sci-fi or futuristic car. It was from Michigan. There was nothing sexy about it; it looked like a family car. But it was a big win, because we couldn't afford to distribute 400,000 demos on our own, or do a TV commercial."

With an unlikely marketing companion in Dodge, Gleason got a TIE Fighter demo onto the PCs of thousands of gamers. In early 1994, Computer Gaming World magazine released a single-mission demo of the game on a pair of 3.5-inch floppy disks. After clicking their way through an ad for the then-brand-new Neon compact, players were rewarded with an early, rough build of the game.

The full release of Star Wars: TIE Fighter launched in July of 1994 to almost universal acclaim. It won a number of industry awards, and, in May '97, PC Gamer named the "Collector's Edition" CD-ROM version of TIE Fighter, which had the more advanced graphics and sound Holland had wanted back in 1994, the greatest game ever made.

"A lot of people grew a lot working on these products; they learned a ton," says Robin Holland. "I'm really proud of our company. We have people telling us, still, that that was the best work experience they ever had. I think they got a really sweet amount of healthy mentoring. I know I brought something to the party because I wasn't just a gamer; I brought formality. Some people might have wished it didn't come, but if you're going to have a team work well together, you have to do that. You have to bring some formality and some ways that we're going to work together. Larry's really good at giving people a voice, and allowing them to express their ideas."

As the story goes, George Lucas was shown the packaging for TIE Fighter in a board meeting shortly after the game had come out and had started performing well financially and earning acclaim. Lucas picked up the box, examined the cover, and then turned it over to read the copy on the back. "'Imperial Navy'?" he said. "There's no navy in Star Wars." A moment later: "Well, I guess it doesn't matter."

"What we were doing mostly didn't affect the greater universe," Larry says. "I think people really enjoyed it, and a lot of people played it."

That success continued with sequels like the multiplayer-focused X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter and X-Wing Alliance, which further tied into the movies and new Star Wars Expanded Universe. But the real legacy is in how TIE Fighter explored the Empire for the first time, bringing a depth to Lucas's galaxy that wasn't there before. Without TIE Fighter, it's hard to imagine later games that pushed the boundaries of Star Wars, like Knights of the Old Republic 2, would have ever been made.

Holland seems pleased when I tell him that Disney's recent animated show Star Wars Rebels, which prominently features Thrawn in its second half, draws on ideas from TIE Fighter, like the TIE Defender program. Larry's especially proud of the game's elite secondary faction, the Secret Order of the Emperor, and how it managed to serve as an organic extension of what would have otherwise been simple bonus objectives. "I liked that element, and how we weaved it together. We had the cutscenes to support it, we had medals," he says. "It caught the interesting relationship with the Emperor and this idea that these are a special group of pilots who get these special tattoos. That's a real highlight for me."

He describes his first time playing the game as though a TIE Fighter were an artifact you might find out in the world, restore, and take flight in.

"This thing, this tin can," he says, "had a whole different feeling. So many of the other games had all these fighters, whether it was X-wings or P-47s, which could handle a lot of abuse. Here, it really felt like we captured the fear factor of being in something that could blow up with only a few shots. I liked that take on things—that emotion that was surrounding you at all times."

Feeling nostalgic? Take a tour through all the classics with our complete history of Star Wars on PC.

Most Popular