The making of Sam & Max Hit The Road

Creator Steve Purcell discusses the characters' origins and the classic adventure game in this archive interview.

Retro Gamer is an award-winning monthly magazine dedicated to classic games, with in-depth features from across gaming history. You can subscribe in print or digital no matter where you are.

This was the first Retro Gamer guest article on PC Gamer, originally published in issue 22 of Retro Gamer all the way back in 2006.

Great double acts are commonplace in the world of film, television and comedy, but games have very few duos that stick out. As far as we’re concerned, one such pairing stands out above all others—and we don’t mean Firo & Klawd. Whether they were gracing the pages of a comic book, the television screen or a PC monitor, Sam & Max is the strangest of teams.

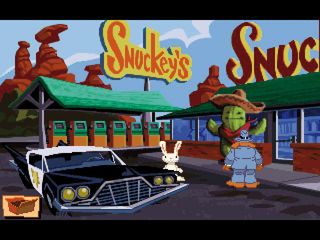

With his trademark suit and dry wit Sam is a typical gumshoe, except, of course, he's a floppy eared dog. His sidekick Max, meanwhile, is a completely naked bunny rabbit with a set of teeth that would put Jaws to shame. The pair starred in LucasArts' Sam & Max Hit the Road, a hilarious adventure game in which the two 'hit the road' in search of a missing Yeti. Along the way they found themselves visiting some bizarre tourist hotspots like the world’s biggest ball of twine and an alligator-infested crazy golf course. The game was both a showcase for the madcap title characters as well as a parody of America’s weird and wonderful tourist sights.

The 1987 comic “Monkeys Violating the Heavenly Temple” was the first appearance of Sam & Max, courtesy of creator Steve Purcell. “My brother made up a pair of characters called Sam & Max when he was a kid,” recalls Steve. “My version grew out of my own cruel parodies of his comic books. At some point he lost interest and I continued drawing them. Over the years, The Blues Brothers and Penn and Teller have also had an influence on Sam & Max and one of our family cars was a dead ringer for Sam & Max’s 60’s patrol car.”

The comic soon gained a strong cult following and eventually grabbed the attention of a few employees at LucasArts. “Ken Macklin, an artist at what was then called LucasFilm Games recommended me (based on my first Sam & Max comic) to the Art Director Gary Winnick. I started on a role-playing game that was cancelled shortly after I was hired and found myself without a job. Fortunately, they hired me back to paint the Zak McKraken box cover. After that I animated on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Working at a game company on Skywalker Ranch was like going away to Geek Summer Camp. It was great.”

It was only a matter of time until Sam & Max were transported from the comic page to the computer screen. LucasArts had been turning around more and more funny adventure games (most notably The Secret of Monkey Island) and Purcell’s wisecracking duo were perfect for the relaxed pace of the genre. “The way Sam & Max work best is that you need to spend time with them as characters. You get used to the way they interact with each other the way you do with a friend when you come to speaking a common language of references and shorthand.”

In 1992, then, LucasArts set about creating a Sam & Max adventure. With only seven-and-a-half months until release, Purcell and the team needed to get a story in place quickly. “We employed storyboarding for the first time at LucasArts, mostly because we needed to plan ahead to keep everyone busy.” says Purcell, who came up with the story by adapting the comics and incorporating events from his own life. “I love the book Roadside America, which is a hilarious travelogue of America’s goofiest tourist stops. My childhood road trips across the US with my family also helped inspire my second comic as well as Hit the Road.”

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The Sam & Max comics were pretty adult in tone and there was always the possibility that LucasArts would want to cut back some of the edgier material for the game, but Purcell was very pleased with how much they allowed him to stick to his original vision. “I think the game is really close to the spirit of the comics. There’s violence, mild cursing and a commendable lack of respect for authority, not to mention circus freaks and yetis. There’s less gunplay in the game simply because a gun is a terrible object to give someone to use in an adventure game unless you carefully guide the player to use it in a more interesting way. I don’t remember anything getting cut by management. Much to their credit, I think they trusted our judgement.”

With the story in place, and relatively un-meddled with, the team carved the narrative into an enjoyable adventure. With the aid of fellow game designers Sean Clark, Michael Stemmle and Collette Michaud, who had all previously worked on Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, Purcell was charged with the difficult task of creating a game that got the balance between story and puzzling just right. “You try to be aware of the amount of time you have players sitting and watching as opposed to interacting. Fortunately a lot of the humour came out of the way that the characters would respond to the player’s actions. Even observing something in the room could produce a funny response, in which case the interactivity is doing the work of the story.”

The Sam & Max team also decided that the SCUMM engine, which had powered all of Lucasarts’ adventure games since Maniac Mansion in 1987, was due for a spring clean. A single mouse pointer, the function of which could be cycled through by clicking the right mouse button, replaced the traditional method of selecting a verb from the bottom of the screen then clicking on an item and/or location. This freed up screen space for more expansive backgrounds, and also made interaction quicker and less laborious than in previous games. In Purcell’s opinion as a writer there were other advantages to the loss of verb lists and dialogue trees. “It may have been Mike Stemmle who first proposed the icon-based interface. I think it’s great for a game that’s driven by a lot of verbal gags. Nothing would kill a joke worse than reading it before you hear it.”

Purcell had another twist he wanted to bring to Hit the Road. LucasArts was aware that difficulty peaks in puzzles meant that adventure games could often “bottleneck”, leaving players with nothing to do if they were stuck. To alleviate the traditionally slow pace of the genre, Purcell added several minigames to Hit the Road, such as Car Bomb, a suitably dark version of Battleships. “They were meant so that when you were tired of trying to solve obscure puzzles you could take a break and play something short and silly,” explains Purcell. “I liked having a grab bag of content so you could jump from thing one to another and try something different.”

As well as the floppy disk version, Sam & Max Hit the Road was due to be released on CD-ROM and, as such, was to be one of the first adventures to feature voice acting. For Purcell, this was a dream opportunity to hear his creations talk for the first time. “I always thought of Donald Sutherland as Sam. He sounds big and intelligent but with a bit of a lisp that gives him sincerity. Although Bill Farmer sounds nothing like Donald Sutherland, I liked his demo tape because it was very dry. He wasn’t trying too hard to sell the lines and he made me laugh. I call his Sam Johnny Carson crossed with Jack Webb, two people that a lot of your audience have probably never heard of.”

At its release in early 1993, Sam & Max was particularly praised for its starring duo, interface, tone and dialogue. LucasArts’ latest classic was incredibly popular with adventure fans and, perhaps partly due to Purcell’s characters, had some crossover success with those who wouldn’t normally buy a point ‘n’ click game. “I’m probably still not allowed to reveal sales figures but over the years it’s sold much better than any of the marketing projections. I remember a lot of people seemed to appreciate the weirdness of it when it came out but others were confused, thinking it was meant to be a cutesy kid’s game. Hit the Road won some awards that year and was on Entertainment Weekly’s Top Ten list for best software.”

Purcell has his own thoughts on why Hit the Road stood out from its LucasArts stablemates: “I think it has the impression of being edgier and meaner, because of the language and aggressiveness of the characters, but as with the characters themselves it’s mostly bluster. Most of the violence and aggression is hearsay, not really played out.”

The game’s popularity has remained strong for the last thirteen years. Re-releases have kept Hit the Road on the shelves and ScummVM (the best emulator ever made?) has opened up virtually every platform to the charms of Sam & Max. Purcell couldn’t be happier that his game is still being enjoyed, despite advancements in technology. “I’m always amazed that people are still playing Sam & Max after all these years. I know that it’s been fan-ported to PSP as well and I’m told the old graphics look great on that little screen. I meet grown people who first played Sam & Max when they were little kids and still take time to revisit it or share it with their friends. Sort of makes it all worthwhile.”

Most Popular