The legacy of Quake

Looking back on one of the most influential games in PC history and the true arrival of 3D.

Quake was released by id Software in 1996. You’ve probably heard of it. What’s less known is that Quake was an idea that had been gestating since id’s early days, back in the era when it was best known for the side-scrolling Commander Keen series. The first Keen promised that The Fight For Justice was coming soon, an epic RPG starring a character called Quake—“the strongest, most dangerous person on the continent,” who would explore an epic RPG world armed with a hammer in what id was already calling “The finest PC game yet.” Instead, it ended up being half a decade before Quake’s adventure came out, almost breaking id Software when it did.

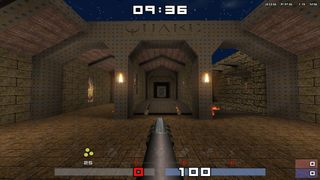

When Quake arrived, it was a true 3D action game—everything built in polygons. Until then, most games had just faked it. Wolfenstein 3D took place on entirely flat maps. Doom offered different heights, but everything was still drawn in 2D. It wasn’t possible to have rooms under rooms and the like. Duke Nukem 3D and other Build engine games, particularly Shadow Warrior, used advanced cheats to fake the effect. When you jumped into water for instance, you were actually invisibly teleported into another zone elsewhere on the map. Quake was truly 3D, doing things like spiral staircases and lava pits for real, and being as twisty and turny as it liked.

There had been full 3D games of course, like Descent, or the Freescape games that powered the likes of Castle Master even as far back as the ZX Spectrum. To do this, though, they typically had to choose between simple and slow. Quake didn’t. It was a technical showpiece and on a decent PC it moved like a greased-up ferret. No excuses. No compromises.

Or at least, no technical compromises. Of Quake’s three great achievements, the singleplayer is easily the weakest. It’s not a terrible game or anything, but where Doom still stands up as a great campaign full of detail and wonderful design despite its simplicity, Quake is a largely bland and joyless experience whose memorable moments were almost entirely restricted to the first shareware episode. They were pretty cool, though. A main menu in the form of a 3D level, with each chapter’s area themed around the aesthetic to follow, forcing you to jump a lava pit to select hard mode and seek out the Nightmare mode in the small level beyond. Big baddie Chthon, hurling fire in his lava lair. The first time having your face eaten off by a Fiend. The low-gravity physics of the secret level, Ziggurat Vertigo. They’re effective, as was the experience of being in a fast-paced 3D world full of action.

Players hoping for a constant stream of such innovation were disappointed. Despite the Lovecraftian influences, there was little to fear or any sense of anything great going on. There were no more giant, dramatic bosses, with the final one, Shub-Niggurath, just being a static blob defeated with a cheap telefrag rather than a weapon. There was little sense of place. The levels were murky shooting galleries, where even Doom had tried to make its locations feel like real locations—to whatever degree of ‘real’ you can get from starbases slowly being taken over by biotechnology. Certainly players coming in from Duke Nukem 3D and its real-world settings and constant variety couldn’t help but be disappointed, even if Quake has honestly aged much better. It’s still dull, but at least unlike Duke it’s not writing cheques its engine long stopped being able to cash, and much easier to take as a simple shooter rather than a bigger Experience.

The main problem was that after years of promises and expectation, to have a game that was basically Doom again—only set in a castle—was something of a letdown both internally and externally. All the RPG features, most planned new gameplay concepts, even the idea of a main character wielding a hammer, had been sucked out, mostly to get the thing out of the door. This led to a major schism within id. John Romero packed his bags to go start Ion Storm and create the more narrative/detail driven game that he wanted to make. (In a case of history repeating, his co-founder Tom Hall had done much the same over the original Doom, which he’d also envisioned as being much more of a story-driven experience than the shooter it ended up being.)

Luckily, multiplayer was a whole other matter. Here, the stripped down simplicity and full 3D allowed for fantastic arena design in genuinely atmospheric levels full of cubby-holes to camp and launch assaults from, and even the occasional gimmick, like hitting a button to slide back a level’s floor and drop unwary players into a pool of lava. It felt great. The weapons had real kick. Gibbing other players was a pleasure.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Outside the game, it helped that by 1996 online play was finally becoming viable for PC gamers across the world. While Doom had spawned a huge scene in its day, getting online in 1993 was a pipe dream for most players outside of universities. At home, gamers were lucky to have a null-modem cable to connect two PCs together, never mind enjoy the fun of epic LAN parties. Of course those who could got to enjoy a truly wonderful experience.

The raw sense of place and weight that 3D offered soon made the fakery of 2.5D untenable.

And so, people played Quake, and saw that Quake was good. The rocket jump alone took Quake to a whole new level. This wasn’t an id invention, but a discovery by fans, so of course the maps hadn’t been designed to handle it. The result? One of the net’s first famous speed-runs—Quake Done Quick, in which the whole game was obliterated in under 20 minutes with tricks like bunny-hopping to raise incredible speed, and rockets to hop through what were meant to be tantalising doors only intended to be accessed after collecting a key or going all around the houses.

Playing fairly or not, the raw sense of place and weight that 3D offered soon made the fakery of 2.5D untenable. It became impossible to ignore that sprites were just two-dimensional, and that when killed, their collapse was a totally canned animation rather than a reaction to physics (though it wouldn’t be until Half-Life that games took the next step and made it standard to give characters skeletons instead of keyframed animation, ushering in the still ongoing ragdoll comedy era).

What all of Quake’s technology really empowered though was its community. It was the first game-as-platform, made possible by not just by the 3D engine, but Carmack including an interpreted language called QuakeC that allowed modders to do more than simply create their own levels and make the monsters look like Bart Simpson. They could completely bend the engine to their wishes.

And the modding community ran with it. When you bought Quake, you were buying into a whole universe of content online. Initially this was limited to simple-but-cool additions, like giving the player a grappling hook to scale and swing around levels in ways that had been impossible with previous 2D engines. Experiments gave way to full ‘total conversions’ like AirQuake, which swapped the players for vehicles and turned deathmatch into a 3D vehicle combat game. Others proved that the sky wasn’t close to being the limit. A little game called Team Fortress, for example, began as a Quake mod, launching with the Scout, Sniper, Soldier, Demoman and Medic classes and building from there.

The ability to create stages, have polygonal characters, and have multiple people control them in ‘scenes’ also spawned machinima filmmaking. Quake’s early examples of machinima may be the Fred Ott’s Sneeze of the genre by modern standards, with celebrated stuff like Blahbalicious and Apartment Huntin’ now looking somewhat… yeah... in the era of Red vs. Blue and Source Filmmaker and whatever the hell people are doing to the Overwatch girls today. At the time though, they were often very impressive, especially when run live in-engine, and did pave the way for something new.

Since Carmack open sourced Quake’s code in 1999, coders have been able to completely overhaul the old engine and bring it much more in line with modern standards. Darkplaces offers real-time rendering of light and shadow, and likely Quake as you remember it looking if you haven’t played it for a while, while others, like QuakeSpasm focus more on accuracy.

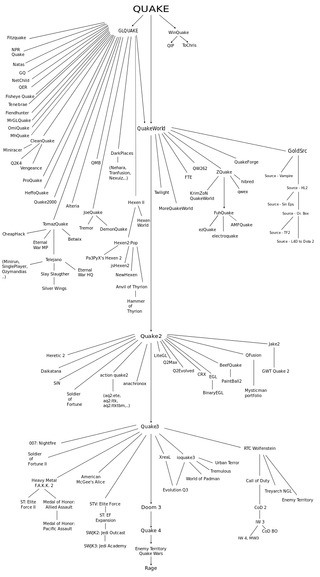

One of many flowcharts mapping the history of Carmack's code, via Wikipedia. Click for full size.

No game since has managed to replicate Quake’s spectacular level of success as a canvas for modding. Others have impressive modding communities, for sure, but not the same scale. With Quake, anything seemed possible—as long as it didn’t take too many polygons. Games like Second Life tried to replicate the phenomenon online, and of course, now would-be programmers can get their hands on the likes of Source and Unity and Game Maker for free or almost free, rendering modding less important—at least for making total conversions or a wholly new game out of the bones of the old.

However long it lasted, the Quake era was important—kickstarting many an industry career, as well as providing the kind of playtime that most games can only dream of supplying. Some mods even got a commercial release, though not necessarily fondly remembered ones. X-Men: The Ravages of Apocalypse, anybody? The answer, in case you’re wondering, is ‘hell no’.

Finally, the Quake story became… weird. After two official expansions (Scourge of Armagon, aka “The One Without The Dragon In It”, and Dissolution of Eternity, aka “The One WITH The Dragon In It”), id disappeared for a while and released Quake 2 as a singleplayer focused sci-fi shooter in which you played a space marine fighting the unfortunately named Strogg. It was not very good. At all. Its main contribution to the world was, along with Unreal, teaming up with 3D accelerators to splash coloured lightning around the world whether it liked it or not. Then Quake 3 ditched all of that for a futuristic arena shooter starring characters like a giant cyborg eye… before Raven’s Quake 4 went back to the Strogg nonsense for another singleplayer focused game.

With Quake Champions, it seems clear a new Quake game is no guarantee of a particular story or style, but rather a way for id to make use of owning the name. Despite that, close your eyes and picture ‘Quake’. What comes to mind isn’t just another game to be ticked off as completed, nor a technical achievement to be respected, but that rare game that blew past its limits. Quake lives on to some extent in just about every shooter that followed it, and made gaming a better, more advanced, and endlessly more exciting place for its existence.

Most Popular