The joys of creation and destruction in SimCity 2000

Destroy something beautiful.

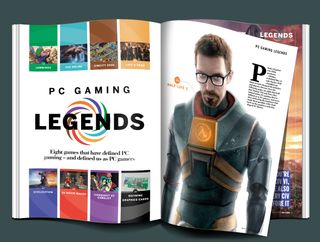

This article first appeared in issue 354 of PC Gamer magazine, in our PC Gaming Legends feature. Every month we run exclusive features exploring the world of PC gaming—from behind-the-scenes previews, to incredible community stories, to fascinating interviews, and more.

I don't think city-building games, despite the perspective of looking down on all the tiny people and making decisions that can bring them happiness or ruin their lives, really make me feel like a god. I usually feel more like a Peeping Tom mixed with an exasperated parent. I delight in just spying on my citizens to see what they're up to, and getting annoyed when they need something from me. "Fine, I'll build you a hospital! Now stop bloody complaining all of the time so I can get back to blissfully squinting at all the little cars driving around."

SimCity 2000 was a revelation to me. I'd played the original SimCity, but SimCity 2000 swapped from the top-down view and 2D graphics to an isometric perspective, which made my little cities feel absolutely alive and real. There was so much detail packed into its pixels, giving every tiny house and park and skyscraper its own personality. In a few days I'd know my virtual city's neighbourhoods and roads better than the one I actually lived in. After building an airport, I could happily watch the teensy, tiny aeroplanes inching across the screen for hours. I always rushed to build seaports just so a little boat would appear in the waterways. It was like a live feed from a webcam pointed at a real metropolis, long before live webcams were even a thing. SimCity 2000 was one of the first PC games to really sink its hooks into me, and I'd often eat dinner in front of the screen, not even playing but just observing.

And when I wasn't just staring at my city, there was so much to fiddle with. Taxes to increase when I ran into money troubles, underground views for laying down utility pipes and subway lines, and graphs showing various attributes of my city that... well, I probably never really understood all the graphs. But at least they were there if I wanted to look at them.

And there was just something so mesmerising about peering down at the little world I was building, seeing the cars on the roads I built obeying the little traffic lights, experimenting with city ordinances, watching the city slowly grow until it was so incredibly big I'd just about run out of room. And then I'd start a new one.

Smash the system

It was also extremely rare at the time: a game that had a beginning but no real ending, with no genuine win-state, or even a way to let you know if you should give up and start over or keep working on the city you had before you. It was open-ended, and you could build and manage your city indefinitely. Once I even left my game running overnight while I slept, just to see if it could sustain itself. I'm pretty sure it was in bad shape the next morning.

There was also the satisfaction that comes along with building something beautiful—knocking it down so I could try to rebuild it again. Disasters could occur, with anything from earthquakes to plane crashes to alien attacks, but I could launch them myself, too, if I wanted a little extra challenge or if my city was humming along so nicely I'd just gotten a bit bored. That's the danger of including a disaster menu at the top of the screen. It's impossible not to click on it once in a while. Boom. There's a flood or tornado or a nuclear accident. Hmm, maybe city builder games do make me feel like some sort of god after all, and not a very nice one at that.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.

Most Popular