The best game design programs, ranked by the Princeton Review 2023

Homework - Directing players: Effective guidance

Summary

From Assassin’s Creed to Spider-Man to Horizon Zero Dawn, open world games give players huge playgrounds to get lost in. However, that presents a challenge for designers—how to prevent your players from getting tired of being lost. There’s a moment in every one of these games where you open up on a scenic panorama or sprawling metropolis and have to pause for a moment and just take it all in, but if designers aren’t careful, it can feel overwhelming. How do you design your game to allow for players to explore, but still have an indication of where the story will take them?

Example

Elden Ring was PC Gamer’s Game of the Year in 2022, and for good reason. It took the Soulsborne formula of bleak, labyrinthine dungeons and challenging bosses and blended it seamlessly into a massive open world experience. It eschewed the usual guidance you find in an open world game—there are very few map icons, no quest logs, and no chatty sidekicks to give you direction. Instead, it relied on a few carefully doled out lines of cryptic dialogue and some vague golden light to guide your way. It also made elaborate use of visual storytelling to clue players in to what was important. When you finish Stormveil Castle, you crawl out of the bowels of the dungeon to find yourself overlooking an incredible vista. Centered directly in the player’s line of sight, framed on either side by massive cliffs and a foul swamp, rises the shape of Raya Lucaria. You know right away that this is important.

Homework

Imagine you are designing an open world game. How would you use the elements of user interface, narrative design, and visual storytelling to guide your players toward your content?

Using narrative design to tell meaningful stories

The stories in videogames have come a long way from ‘some big spiky turtle guy stole your girlfriend, go find her!’ Nowadays, we see complex narratives that not only result in compelling gameplay experiences, but that get converted into HBO shows that can bring you to tears on a Sunday night. Videogames are not just playable movies, though—and treating them as such misses a big part of what makes them special. A narrative designer is a person who shepherds the game’s story through the development process, blending it with systems, writing, and lore.

It might be helpful to talk a little bit about what we mean by story in the first place. After all, the story of a game can refer to many different things. It can be the tale of how Cloud Strife and his band of heroes save the world from Sephiroth (and his mommy issues), but it can also be the way you crafted a huge wolf pen in Valheim and became an animal trainer, or how your guild dropped Algalon the first time in World of Warcraft. Games are, at their core, about experiences, and a narrative designer helps their team blend the plot and writing with the mechanics and art to give players the best possible experience.

An example of this kind of blending comes from the OG boomer shooter itself, Doom. There are many ways for a game to communicate to its players how much health they have left: Bars, numbers, orbs, gauges, red flashing screens, all manners of uncomfortable grunting. In Doom, there was a bar on the HUD at the bottom that displayed the percentage of health you had left, but it also had a portrait of your intrepid marine that got more bloody and battered as your health dropped. By doing this, the design team blended the story of the game with the mechanics in a way that made the game world feel more alive and lived in, and let you connect with the otherwise silent protagonist in a deeper way.

Sometimes gameplay elements can lead to breakthroughs in narrative, and vice versa. In the development of Deus Ex, the design team had a system where the character installed cybernetic augmentations in various body slots, boosting their aim, speed, or strength. By pondering where these augments came from, the team took a mechanical element of the game and were inspired to write more backstory about these black market augs and their origins, even leading to the thought that some of them might have drawbacks coming from chop shop cyber docs.

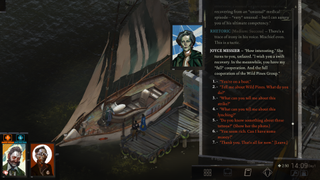

Stories in games don’t necessarily go in straight lines, either. Take Disco Elysium, for example. In this brilliant game about an amnesiac, alcoholic detective, you have a ton of freedom in how to go about solving the murder at the core of the game’s story. The decisions you make, the people you talk to, and the order that you do those things matter a lot, and can fundamentally change the outcome of what happens to our dear Harry DuBois and the other characters. A narrative designer might be in charge of keeping track of all those branching paths, and working with the rest of the team to ensure they all make sense.

As the stories in games have become more complex, so too has the process of creating them. People who work in narrative design tend to wear many hats, taking an active hand in everything from script writing to systems design to directing voice talent. If you’re interested in this element of design, be prepared to work closely with other members of your team, bringing the vision of a game’s story to every element of the production.

Pay close attention to the next game you play and ask yourself what elements of the gameplay help tell the story, and vice versa. What’s working, and what could be better? How would you improve it? What is it doing that’s great, making you feel immersed and committed to what’s going on, and where are the pain points pulling you out? By doing this, you’ll start taking your first steps on a journey toward thinking like a narrative designer.

Current page: Homework - Directing players: Effective guidance

Prev Page UNDERGRADUATE RANKINGS Next Page GRADUATE RANKINGSThe biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.