System Shock 2: How an underfunded and inexperienced team birthed a PC classic

"We were given an enormous amount of responsibility, and for not very good reasons."

For me, System Shock 2 is one of the all-time greats. Tying together sharp storytelling, taut gunplay and RPG character development, all set on a claustrophobic spaceship that drips with horror-inflected tension, it was the gateway to the immersive sim classics to come, such as BioShock, Dishonored, and Prey. For its makers, though, System Shock 2 was a test.

It was the first project by a new studio called Irrational Games, a chance to prove it could deliver a game that matched the calibre of Looking Glass, the developer of the original System Shock, Thief, and other PC classics. "It was probably the most pressure I’ve felt in my life," says Jonathan Chey, one of its three lead developers. "My strongest motivation was not wanting to look like a fool, because we’d never done anything like this before in our lives."

Now, over 20 years later, Chey can say the gamble worked. System Shock 2’s sci-fi horror adventure made Irrational Games’ name, laying the foundation for a future in which it would make the likes of SWAT 4, Freedom Force and, of course, BioShock, and lately, Chey has found himself returning to it for inspiration. At the time, though, it didn’t quite light up the charts. Sure, it was critically lauded, but for Chey and his fellow founders, Ken Levine and Rob Fermier, it was simply enough.

These three developers, two programmers and a writer, met after joining Looking Glass, where Fermier had worked on the first System Shock. Ken Levine had contributed to Thief: The Dark Project’s initial story and design, while Chey programmed for Thief and Flight Unlimited 2. They were young and not terribly experienced, and they wanted to found their own company. But they had already learned something important from Looking Glass.

"They weren’t a company that did small, highly polished products," says Chey. "They were a company that did vast, sprawling, ambitious things that always overreached. That’s one of the things we really loved about their games, and we inherited that kind of ambition and way of working, which was to do things that were probably—well, definitely—well beyond what was realistically achievable with the budget and time and personnel that were available. That’s how we were taught to make games, and the only way we knew to make games."

They decided on a name (rejecting Chocolate Milk Productions and Underwater Horse) and scored a deal with French publisher Cyro to create a singleplayer campaign for an isometric action game called FireTeam. But they were left hanging when Cyro decided to make the game multiplayer-only. Fortunately, they’d stayed friends with their former employers, who rescued them with a huge opportunity: a sequel to System Shock, the already celebrated first-person sci-fi RPG which Looking Glass had released in 1994. "We were given an enormous amount of responsibility, and for not very good reasons," says Chey.

The team took a couple of rooms in Looking Glass’ office, some staff, the Dark engine, which was still under development for Thief, and a meagre budget of $700,000. "The whole development process was us pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps, not a very big budget, and trying to put together a team and run a project and do things we’d never done before," says Chey. "So most of the time we were just trying to stay afloat, and to come up with good ideas. We certainly didn’t have expectations about producing something that people would really enjoy, though of course you’re always hoping for the best."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Character-building

But the team worked well together, dividing up responsibilities so that Chey managed the project, Levine was in charge of design and story, and Fermier was in charge of technology. And they all agreed on a very clear vision for what they wanted to make: a worthy follow-up to the original System Shock but with a stronger story and a greater focus on character building and mechanical progression. "System Shock was maybe trying to be a bit cleverer than we were," says Chey. "It was trying to innovate on almost every front, whereas we kept a lot of the core principles, and then layered more conventional RPG systems on top."

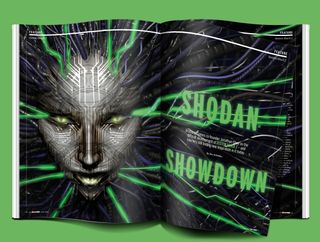

System Shock, after all, had transposed Ultima Underworld’s pioneering fully 3D first-person roleplaying to a sci-fi setting only a year after Doom’s release. Trapped on a space station which had been taken over by SHODAN, its now-homicidal AI, your task was to explore its tightly wound decks, fight cyborgs, solve puzzles, and envelop yourself in cyberspace, in order to stop it firing a mining laser on Earth. There was a lot going on in System Shock. You could even play little games of Pong and Missile Command in its UI windows if you wanted.

But though it had evolved from an RPG, System Shock focused on action and gave little opportunity to develop your character. A door was left wide open for Irrational to build on it. "I guess we figured out a little earlier than some other people that it was very easy to add RPG mechanics to all kinds of existing game types, and that in doing so you made the game much richer," says Chey. And so in System Shock 2 you level up your various skills—hacking, energy weapons, psionic powers—and attributes with the Cybernetic Modules you’re rewarded with and find scattered around the decks of its setting, the science ship Von Braun. You find nanites, which are a currency for buying items from Replicators and paying for hacking into terminals and locked crates. You can also choose between some powerful O/S Upgrades.

These systems let you create with a good degree of freedom your own character build as you run through the Von Braun: do you want to be psi-powered adept, or a soldier? A hacker and repair expert? The multiple ways of facing the storyline’s challenges prefigured the similar focus on stats and skills that came in Deus Ex in the following year.

Although they were a big part of System Shock 2’s appeal to players, for Chey its RPG features were simply a product of the budget he had to work with. Having seen Half-Life release during development, he knew that they didn’t have a chance of building a game with anything like the sophistication of its AI or its scripted in-engine narrative sequences. "We had to do things that were relatively cheap to implement," he says. "RPG mechanics are quite cheap to build and they’re very satisfying."

Levine’s story, meanwhile, would have to be told through emails and voice recordings, just as they were in the first System Shock. It’s decidedly functional, but the way it’s delivered within the fiction of the world gives immediacy to a tale in which SHODAN is now on your side—or so it appears—as you both battle a worse threat. As she snipes and chastises you for not performing her tasks fast enough, System Shock 2 sets up a theme about player agency which Levine would go on to play with in the excellent BioShock.

But for all System Shock 2’s achievements and legacy, it was a stepping stone. Chey feels its sales potential was hampered by its budget, and the studio’s fortunes were hampered by a deal they’d struck with Looking Glass which meant that even if it was a hit, Irrational wouldn’t have made much money out of it. "God knows what our royalty percentage was," says Chey. "I’m sure it was tiny. We had no expectations of becoming rich. Our strategy was, let’s make a really great game to set us up as a developer that people would want to work with in the future and so we could cut a better deal for our next product."

I don’t regard BioShock as dumbed-down. I regard it as a much more accessible version and, in fact, much smarter about a lot of things.

Jonathan Chey

Sure enough, the studio’s next game—Freedom Force, which Chey directed—got a much bigger budget. "We were able to spend a bit more time and we weren’t quite so much against the wall." And eventually, after Tribes: Vengeance and SWAT 4, they commanded enough money to make BioShock, which added big-budget presentation and sanded down some of System Shock 2’s rougher edges (inventory system, interface, weapon degradation).

"Some people, I’m sure, would think it was dumbing down the product, but I don’t regard BioShock as dumbed-down. I regard it as a much more accessible version and, in fact, much smarter about a lot of things. There was a lot to learn from System Shock 2. We’d thrown a lot of things together very quickly and some of them worked really well, and some of them didn’t." BioShock was the studio’s first true hit.

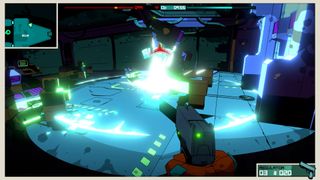

Chey left Irrational in 2009 and founded a new company called Blue Manchu. Its first game was something completely different, the excellent collectible card-cum-turn- based strategy game Card Hunter. But as he began to plan its second, Chey replayed System Shock. He found himself enjoying its combat and the way monsters roam the ship, but didn’t like the way that there’s little point in revisiting cleared areas of the ship. So at the core of Void Bastards, the rogue-like first-person shooter his studio released in 2019, Chey was exploring System Shock 2’s combat more deeply, translating many of its simulation-based features, such as the way monsters respond to audio, lockable doors, and a wide toolset of weapons and traps, into endless procedurally built levels.

"A lot of it felt very similar to make," he says. "I ended up writing some of the same code I wrote nearly 20 years before." And he’s been revisiting System Shock 2 in another way, too. One of his favourite games of the past decade is The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, in which he can see echoes of the System Shock series in the way its systems interact, such as rolling physics balls down hills and using the Rune abilities. "I felt that the designers must have played some of the games we worked on, or the games that influenced us, and because I loved that game so much, that was a wonderful feeling. One of the [most] satisfying things about being a creative developer is feeling you’re part of the ever-growing state of the art."

Most Popular