Roblox faces new allegations of being unsafe for children

The second part of an investigation into the popular sandbox gaming platform highlights a potentially dangerous lack of moderation.

PC Gamer described Roblox earlier this year as a "gaming megaplatform making its own rules." Unfortunately, some of these rules seem clearly designed to protect Roblox from legal liability, rather than to keep its young-skewing community from harm. YouTube channel People Make Games dug deeper into the matter in August with a video alleging exploitative practices at Roblox, and it has now followed up with a second video focusing on Roblox's collectibles and black market.

The new video begins with a breakdown of Roblox itself, which at its core is a development platform rather than a game, but one aimed primarily at kids. Over the years, some of the creations on Roblox have become quite popular, which had the knock-on effect of encouraging ambitious kids to join development teams in pursuit of the next big hit. And big money, too: One Roblox studio, Toya, raised $4 million in funding after Miraculous RP: Quests of Ladybug & Cat Noir—released in May—became a big hit. But because many of those teams are organized and operated on other platforms like Discord, they're outside of Roblox's rules and effectively unregulated.

It sounds like a microcosm of capitalism, which would be fine (insofar as capitalism is fine, at least) except that, as mentioned, Roblox is geared toward kids, who are generally not known as good decision-makers or money managers. To illustrate the point, the video features interviews with individual developers, including Jack, who managed to produce a Roblox hit when he was only 13 years old.

His game earned roughly 200,000 Robux, Roblox's in-game currency, which works out to roughly $700—a good chunk of change for a 13-year-old. But instead of cashing out, he blew most of it on a handful of very expensive in-game items. And because Roblox requires a minimum balance of 100,000 Robux to cash out—a seemingly arbitrary amount, possibly intended to ensure Roblox isn't swamped with requests to convert small amounts of money—once his balance was below that amount, he was stuck.

But this wasn't the end of it. A few months after acquiring those items, Jack lost them when another Roblox developer shared a purported asset that turned out to be a trojan. His presumed friend took the assets and quickly sold them at a discount, and Roblox support refused to assist because he appeared to have sold the items himself. Even worse, Jack was unable to continue earning Robux from his game because it was removed for using assets taken from another game. But those assets were provided through official Roblox channels: They were uploaded to Roblox's toolbox by another user and then made available to its community at large.

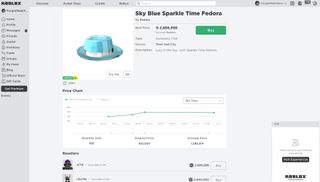

Roblox's official collectible market falls under particular scrutiny in the video because of the way it incentivizes users to buy and sell items. They're vanity items—the more exclusive, the better—but they're also presented as a way to make money: Item pages include a prominent "price chart," the sort of thing you see on stock market pages, that emphasize their monetary value. Some of the items are astronomically expensive: The Sky Blue Sparkle Time Fedora, for instance, is a unique, limited edition hat released in 2016 that originally cost 100,000 Robux—no small amount of change for a little lid that doesn't actually exist. But its "value" has soared since the beginning of 2021, and now sits at an astounding 2.9 million Robux, more than $10,000 in real money.

Roblox takes a 30% cut of all transactions conducted through its marketplace, but it also tolerates unofficial markets because, according to the video, they enable everyone to buy and sell digital items for real money, including developers who have been suspended from the official store for breaking Roblox rules. Unofficial markets also enable players and creators to buy and sell directly, at lower costs, and while Roblox doesn't earn any money off those sales, it does encourage creators to continue using the platform. Officially, Roblox has policies forbidding the use of black markets and will ban the accounts of anyone caught using them, but according to the People Make Games video that off-the-books activity has become so enmeshed in the broader Roblox economy that the company turns a blind eye to much of it.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Markets for cosmetic items in videogames, official and otherwise, are nothing new—CS:GO has been doing it for years—but what makes the Roblox situation so egregious is that the system targets kids first and foremost. The company said in a 2020 SEC filing that as of September 30, 2020, 54% of its users were under the age of 13. Unofficial digital marketplaces are fraught enough for adults, who (hopefully) have some grasp of the risks involved in handing out credit card numbers to unknown online entities; it's unreasonable to expect a 12-year-old to even think about such risk, much less navigate them effectively.

Roblox has been around since 2006, and its popularity continues to grow, as does its value: Ahead of its public listing earlier this year, Roblox was valued at more than $29 billion. Given that, you can understand why the company would be reluctant to mess with the formula too much. But increasing public scrutiny, not just of its exploitative developer practices but also straight-up safety issues such as allegations of grooming and far-right recruitment, may force the issue. At the very least, it seems inevitable that more attention will be paid to what's happening on the platform—and, hopefully, how it handles and protects its young community.

Andy has been gaming on PCs from the very beginning, starting as a youngster with text adventures and primitive action games on a cassette-based TRS80. From there he graduated to the glory days of Sierra Online adventures and Microprose sims, ran a local BBS, learned how to build PCs, and developed a longstanding love of RPGs, immersive sims, and shooters. He began writing videogame news in 2007 for The Escapist and somehow managed to avoid getting fired until 2014, when he joined the storied ranks of PC Gamer. He covers all aspects of the industry, from new game announcements and patch notes to legal disputes, Twitch beefs, esports, and Henry Cavill. Lots of Henry Cavill.

Most Popular