Prison Architect: how Introversion avoided jail by embracing their hardest project yet

This article originally appeared in PC Gamer UK issue 256 .

Prison Architect has sold 124,691 copies and made a gross revenue of £2,679,730 ($4,031,925). If you're one of the remaining major videogame publishers, that's pocket change, but if you're Introversion it's more money in ten months of alpha sales than your previous four games made in over 12 years. If you're Chris Delay, the game's lead designer and programmer, it's the opportunity to start a family. And if you're the three founders - Chris, plus college friends Mark Morris and Tom Arundel - it's the difference between being comfortably wealthy and living in fear of spending time in a real prison.

“Tom was convinced that we were going to go to jail,” says Chris. “He was convinced that we were going to go to jail because he thought that for most of 2010 we'd been trading insolvently, which means trading knowing that there's no chance you're going to survive.”

Prison Architect is the game that saved Introversion, one of gaming's most interesting and longest-serving indie developers, but if you're a gamer then it also represents a bunch of other, similarly excellent things.

It's intensely British, like all of Introversion's games. This time, it's a continuation of what Peter Molyneux and Bullfrog were doing in the '90s, crafting darkly funny management games like Dungeon Keeper and Theme Hospital.

It's proof that alpha funding can work, benefitting everyone involved by giving Introversion the money they need to make the game, and letting players be a part of that process from an early stage.

And it's another example of how videogames are at their most exciting when they put control in the player's hands. Prison Architect will have a story-driven campaign mode, but at its heart is a rich, Dwarf Fortressinspired simulation of tiny digital men, their needs, their grisly crimes, and even their families.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

In its alpha state, that campaign mode hasn't been added yet. Play the game today and you'll begin instead with an open field and a ticking clock counting down to the arrival of your first batch of prisoners. Before they arrive, it would be prudent if you had built them a holding cell, using the few starting materials and handful of workers provided.

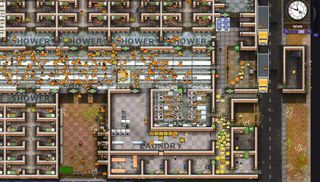

Once they arrive, your next steps present themselves naturally. People need go to the toilet and shower, forexample, so you'd better place those things. You'd better place a water pump too and lay the pipes for that. Also, people need to eat, don't they? So you'd better build a cafeteria and stock it with benches and tables, and create a kitchen stocked with ovens and chefs.

And since some of the people in your prison are murderers, you should hurry to place some locked doors on that kitchen, and hire guards to patrol the cafeteria to stop your captives from fashioning shivs out of sporks (shorks). And also, wait, they need to sleep, so some beds are needed, and probably cells for privacy, and solitary confinement for punishment.

And suddenly it's four hours later, and the 150 prisoners now trapped within the walls of your failing prison are rioting, and escaping, and you're broke, and you can't quite remember how it all went so wrong. So you start again, and vow this time to do it all better.

Or instead, maybe you open Steam Workshop and download one of the hundreds of prisons built by other resourceful players, to see how it's done. You install huge, sprawling mega-prisons, and prisons in the shape of the FTL spaceship, a space invader, and the Tower of London. There's a vast amount of content here, and even with the game incomplete, a tremendously dedicated community.

“When people buy into an alpha now, it's questionable as to whether they're even buying the game itself or whether they're buying into a process: to see a game be developed and be a part of that,” says Chris.

“For me, with DayZ, I was there in the beginning. Back in those days, it was updating every week, and it was extremely exciting because there was all this new stuff going in all the time, really big game-changing stuff. I wanted it to be like that for Prison Architect: that every update would add something big and meaty that would make you reconsider the game again, like 'I'm going to build a whole new prison as a result of this because the whole game has changed again.'”

Steam Workshop support came in alpha version 8, released March 20, alongside a new planning mode. Alpha 9, released April 24, brought the ability to put your prisoners to work in your laundry, kitchen or workshop. May 30's Alpha 10 added riots and riot guards, and June 28's Alpha 11 added hearses, allowed prisoners' sentences to end - which I'm sure they appreciate - and introduced native support for generating timelapse videos.

Looking at these monthly updates stretched out behind and in front of the game, you quickly get a sense of how big a project Prison Architect is. As Chris and I talk about the issues that surround the game - from its simulation and its politics - I also quickly get a sense of how difficult the project is. It's an example of an indie developer tackling a huge, unexplored mountain, of the sort mainstream development might find too risky to scale.

The monthly update schedule means that by the time you read this, Alpha 12 will have been released. Chris isn't shy about talking about Prison Architect's future.

“I'm working on contraband and stealing contraband from around the prison,” he starts. “Gary's working on dogs and dog handlers. The idea is, because there's going to be a lot more contraband floating around the prison, dogs are going to be there, primarily detecting narcotics and booze and poisons and anything that can't be detected by a metal detector.”

A lot of the game's development works this way: every system is interdependent, so long-requested features sometimes take a backseat until the groundwork has been set.

“We actually have escape tunnels working right now,” says Chris. “A few prisoners can dig escape tunnels. They intelligently dig around buildings, and if two prisoners are digging, they join up and form one master tunnel digging out, Great Escape-style. But we've never put it in the game because there was no way for the player to deal with it.”

Dogs are the way to deal with escape tunnels, too. “Dogs on patrol around the edge of the prison will bark and scratch at the floor when they walk over an escape tunnel.”

Most Popular