Playing a game within a game in The Magic Circle

I’ve just reprogrammed a dog to attack mushrooms. I’m told I’m the second person ever to do this—the first being former PC Gamer writer Tom Francis, coincidentally. I created this scenario with a seething ‘some men just want to watch the world burn’ mentality.

The dog is actually something called a howler. I can reprogram any creature in this environment. I can customise how they move, who their enemies are and who they consider allies. I’ve started this demo with a dog attacking a mushroom, but I’ll end it by charging into battle controlling a miniarmy composed of a flying fireproof dog, a brave turtle who is constantly being killed and a fire-breathing helicopter robot that can possess other helicopter robots but can no longer fly.

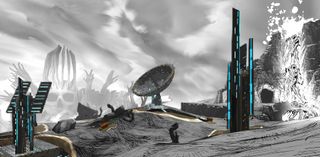

Created by ex-BioShock staff Jordan Thomas and Stephen Alexander, and Dishonored AI programmer Kain Shin, The Magic Circle is a game about reprogramming NPCs in a mini-sandbox, set within a game that’s stuck in development hell. I first sampled it back at GDC earlier this year, and since then it’s come on a long way in terms of how intuitive it is to play. The goal is to confront the Sky Bastard, essentially the creative director of the game-within-the-game (which is also called The Magic Circle). This context is introduced via a mainly noninteractive opening that takes the form of a generic black-and-white fantasy RPG revenge premise, which is being talked over by the game’s creative director and a dissenting member of staff. Things aren’t going well on the project, and it’s about to get even worse.

Once the fantasy fluff ends, your character literally walks through the title screen of The Magic Circle into the back-end of the game, as it were. Here, an entity from a previous version of a game made by this team urges the player to help him wreak vengeance on the Sky Bastard. This leads you through an evocatively System Shocklike retro sci-fi environment and you’re taught how to reprogram AI, which is the core conceit of The Magic Circle. You’re then dropped into a mostly black-and-white open world. From here on, it’s down to you to explore this sizeable hub and solve puzzles to help you gather the skills to eventually take on the Sky Bastard.

The game’s title also refers to its key means of interaction. Before I can reprogram NPCs, I have to capture them in first-person by drawing a circle of light onto them—this freezes them so I can approach them and begin reprogramming. Let’s say I’m being attacked by a howler, the aforementioned standard enemy dog NPC. I draw around the howler and stop it in its tracks. I then walk up to it and open up the ‘inventory’ menu, where each behaviour for this enemy is listed on a late ’80s-style green-screen menu—as mentioned, this includes who their allies are, their enemies, the way they attack and even special attributes (I can make a character fireproof, for example). The more NPCs you try this on, the more values you collect and can later use to reprogram other characters. So, while at first all I can do is make the howler attack a mushroom with a melee attack, later, when I’ve used the circle on a character that breathes fire, I can change the howler’s attack patterns from melee to fire-breathing.

Once you’ve captured a creature, it’s yours to summon from the map screen at any time. You can set waypoints for creatures to help them do your bidding—what starts as having a battle pet soon turns into managing a squad of augmented creatures whose nature you have defiled, like those fucked up but benevolent toys in Sid’s room in Toy Story.

Eventually, once I’ve explored the environment in full, I turn my ordinary howler into a flying, fireproof beast who gets around with a little helicopter rotor on his back and vanquishes anything that isn’t my friend. It’s a satisfying arc, getting to that point, and I have a nice sense of ownership over the creatures I’ve mangled to my satisfaction. And that urge to experiment grows as you unlock more values to play around with. Every new enemy is an opportunity. When I first gain the ability to make any of my little guys fly, it feels like a real breakthrough moment. Let’s improve a turtle!

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Combat is one application of crafting a mini army, but progress actually relies more on lateral thinking and treating the environment like a puzzle—one seemingly simple example is a river of lava that you have to cross. Thomas would rather I didn’t give the solution away, but it’s neither obvious nor straightforward to pull off—nor is it the only solution. What these puzzles do is galvanise your enthusiasm for programming and reprogramming the characters, in a build up to your assault on the Sky Bastard, who’s represented by a glowing eye in the distance (reaching him was the final puzzle of the demo).

With such scope for self-expression, your experience may be entirely different from mine, but you won’t resolve these situations without a lot of chopping and changing in the inventory menus. My programming of the howler to attack a mushroom was evidently a rare decision. You can pick your own inanimate objects to devastate.

I haven’t gone too in-depth with the story here, and that’s because I want to leave some of it as a surprise—living in a game stuck in limbo is an original and compelling situation (not to mention one that’s quite tough to explain on paper), and wandering out of the existing black-andwhite world and into System Shock-like chunks of environment is a real treat. But even outside of this narrative, The Magic Circle is systems-driven in a way that’s very exciting for a player like me—the kind who likes to put a bit of himself into a game. I think the specific audience that finds this is going to love it.

Most Popular