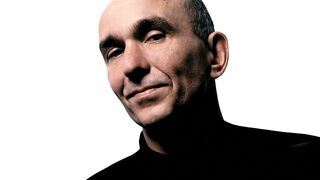

Peter Molyneux on press exile, No Man's Sky and kickstarting his career

The controversial developer is back with The Trail: Frontier Challenge.

Despite his '90s and early 2000s acclaim at Bullfrog and Lionhead Studios, industry mainstay Peter Molyneux has more recently acquired a reputation for overpromising. This reached fever pitch two and a half years ago when he came under immense press scrutiny over his much-maligned god game Godus.

The Trail marks his latest venture which, after finding success as a free-to-play mobile game, has since come to PC bringing with a number of nips, tucks and adjustments.

I caught up with Molyneux over Skype to chat about what his latest game does differently on desktop, how he's spent the last couple of years in exile from the press, and what the future holds for the divisive developer.

Peter Molyneux is a long-serving game developer best known his work at Bullfrog Productions on Theme Park, Theme Hospital, Populous and Dungeon Keeper, and Lionhead Studios on Fable. He now works at 22 Cans, the studio he founded in 2012, and has recently launched The Trail: Frontier Challenge—a PC port of a mobile game of the same name.

PC Gamer: What are the main differences between The Trail's free-to-play mobile version and its premium PC version?

Peter Molyneux: The main differences between the two are that in the PC version you have the option to unlock hundreds of different unique skills for your character, so that you can buff and improve certain elements of you character. Every single campsite that you go through as you progress present a whole variety of different challenges that you face. Some of those can be while competing against other people.

We've also completely rebalanced the game and have implemented new features for when you get to a town and cooperate together as townsfolk. That is has been completely reordered. The only thing that's really been kept is the backpack management and the ability to trade with other players. Everything else we've reimplemented, or recrafted or have implemented from fresh.

Tell me more about The Trail's backpack management.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

We did quite a lot of work on designing the backpack feature, it's a physical thing that you have to squish things in. There's a real skill in trying to get as much stuff into your backpack as possible. Going forward to the PC version, there's the realisation that people love to be challenged. As you progress, you're challenged at every campsite you go through and that enables you to unlock different skills and lets you specialise in being a hunter or being a lumberjack or being a tailor.

All of this is in service of when you finally reach places that you can settle down and call home. When you do that, you join a community of other people, other explorers that have been going out and collecting stuff and becoming different hunters and different classes. Then once you're part of a town, you and the other town members cooperate with one another to try and make your town the best town. There are certain rewards in making your town the best town. All of that was inspired by the original Oregon Trail. So that's the very fractured two minute pitch.

Unlike Godus, where Curiosity was in essence a marketing pitch for the eventual game, the Trail came to iOS with almost no fanfare. Why did you approach it in this way?

The thing is, Joe, it's a very brave person now that pre-hypes a game. I'm not saying it can't be done, I'm sure there are far more skillful people than me that can do that but in today's world I think all types of people—consumers, not just gamers—they want you to talk about something that they can get their hands on, that they can try out for themselves. That's the world we live in now. I think there was an interesting argument in saying: If I'm someone who is fascinated in the process of making a game, maybe there's some way that I can discover that. But the traditional approach of the 1990s and 2000s of hyping your game up and going out and showing incredible trailers and doing lots of interviews and then launching the game—I just don't think the world works like that anymore. I think it just annoys people.

I think they interpret words like 'exciting' and 'great' in reference to story etc. as being promises that are there to be broken. This time round, I think it made an awful lot more sense to work on the game. I must admit Joe, I do really miss talking to the press and talking to consumers while the game's being developed because you get feedback about certain concepts within the game. Working on the game and then releasing it made more sense.

No Man's Sky seems to fit that description in modern context. I understand you visited Sean Murray shortly after NMS was released?

Yeah. I mean, it was an incredibly harrowing time for him and it had been an incredibly harrowing time for me to suddenly realise that the world has flipped and changed from one state to another. Quite obviously with No Man's Sky and some of my games in the past. People get very, very frustrated that the game isn't as they imagined or as it had been portrayed to them as they imagined. You can completely understand that in today's world, you can absolutely understand that. And of course when people get frustrated in today's world, they can be incredibly vocal about it which creates a tide of what people think.

For us, for me and Sean and whoever, we, hand on heart, we make these games because we love making games. We make these games because we want people to love making the games that we make. I can assure you that me and Sean and lot of other people I know aren't in this to steal people's money away, we're not in this to be evil; we're in this to try and make things that entertain people that we can be proud of.

I understand that in taking a step back from the press you've refocused your attention on coding, is that correct?

Yeah, that's right. When all of this happened, it was incredibly… I mean, I won't go into any detail, but it had an incredible impact on me, on my confidence, on my health, a lot of things. I thought: what am I going to do about this? I could sit in a corner and sulk and hide away, I could run out and become angrier than anybody else, or I could do that I think is the best thing to do. That is to relearn the art of coding, which I'd stopped doing on Black and White and hadn't done any since then. It took me quite a few months to get back into the swing of coding again and that's exactly what I'm doing—this is the first project that I've coded on since Black and White.

I've got a load of code on the screen at this very moment, it's a project codenamed Legacy and I obviously won't tell you anything about it because of everything I've just said but I'm finding that unbelievably exciting and exhilarating and really empowering. There are many times where it's one or two in the morning and I'm just giggling with excitement but I can have an idea and instantly get that idea into the game. I'm finding that super exciting.

A couple of years ago, you said you'd sworn off talking to the press following an interview with another publication. What's changed?

When I had that interview with Rock, Paper, Shotgun, I said that explosive thing. It was a slightly childish thing to say and it was in the heat of the moment. Looking at it now and what is sensible, it'd just be silly and stupid and childish for me to refuse to talk to people like yourself. Ultimately, this game has just been released so a lot of the press will want to talk to the principal designer on the game. We should do that, we should have that chat, but what I shouldn't do and continue not doing is to pre-hype games before they're out. My rule is simple: I'll talk about a game if it's released, if it's out, and players can get their hands on it. The thing that I'm fascinated to talk about is the background—where a design came from, where an idea came from and how it evolved.

Do you think you've been guilty of over-hyping in the past?

When it comes to work I'm such an obsessive, to the point where it becomes the only thing in my life. When you're working with people, part of your role is to find the exciting elements of the game. It's very hard to filter that out and think: oh gosh, I mustn't say that because that may not come to fore. I've been very guilty in the past of being just too excited about the thing that I'm working on at the time. People may or may not believe it, but I'm never doing this thinking: oh, this is going to sell 10,000 more units if I tell this lie. To me, it all really started back in the Fable days when I said to the press, we're going to make the greatest role-playing game of all time. That was the first time that that line was really taken and interested.

But, as I said, when you're standing up to a team, you don't go up to a team and say: Right, we're going to make quite a good role-playing game, not the best one, though. You've got to get a team excited and it's only the excitement and enthusiasm that actually makes any note. But, as I said, those things if they're written in the wrong way and are read in the wrong way, they can be taken as promises. If you say to me, okay, the next Spider-man film is going to be the greatest film of all time, my anticipation is going to be up. I think in today's world you've got to be very skillful with the message when you're talking to consumers, especially about something that doesn't exist. If that thing does exist, then I think you should comment on it and discuss why you took this approach or that approach.

Speaking to The Trail, you've spent quite a while now working in the mobile spectrum—how does that compare to that of PC?

The thing that fascinates me about mobile is that it contains a lot of people who have never really played games before. A lot of those people don't really realise what games are capable of, they don't realise that they can play a game with thousands of other people together. They can feel that sense of community. In The Trail's case, this might be in joining a town. They can get their sense of accomplishment by working together and that might be the first time they've ever experienced that in a game, and I find that fascinating. I find that fascinating as a designer to present things that we in the game world have been doing for many years to consumers who have never done this before. Before that, they've maybe thought that games aren't for them. Giving players something new and different is fascinating.

I also think that there's this unbelievably exciting thought when you're designing for mobile is that mobile devices are with people all the time. Instead of scheduling their time in front of consoles or PCs, mobile players can reach into their pockets any moment of the day and engage with the thing that you've made.

When did you decide to port The Trail to PC?

Late last year we considered what it would take to make The Trail that could be played by people who enjoyed PC games. This was made in Unity so it's a case of pressing a button and it's available on PC, it's that simple, but we also thought: what would it take? There was huge debate about whether or not we should allow you to explore the world, whether or not we should open the world up more than it currently is, whether you should be allowed to go forwards and backwards on the trail, whether or not you should be allowed to go into the bushes, whether we should continue to focus on collecting and backpack management.

We decided that we wouldn't do that. We then said to ourselves: is it right for this to be free-to-play or would it be better to be a more traditional experience where you pay once at the start. We decided that it would be a better game for the PC audience if it was pay once, and if you're going to do that then that starts to introduce this idea of skills, unlocking skills, becoming the person in the game that you want to be. We tapped into this idea that you have hundreds of challenges to take on in the world—some against other players, some against the game itself. What we ended up doing was keeping the core of what the game is—travelling along the trail, collecting stuff, trading with other players, finding a place to settle—and reauthored a lot of the motivational mechanics.

The mobile version of The Trail seems to have evolved considerably since launch—are you aiming for something similar with the PC?

Sure, we'll have to see. The interesting thing about today's world with releasing stuff is that you never know when you're going to be finished. The only thing that defines whether or not you're going to be finished is whether there are enough people interested in it to cover the costs of continuing to maintain and update it. If that is the case then we would love to continue to evolve The Trail, and there are people working on evolutions of The Trail as I look over at the team at the moment.

It's a very tricky thing these days, though, Joe because you never know when to plan to move forward. There are so many different formats, there are so many different things to update, there are so many different opportunities. It's a real… not a headache, but it's a real interesting problem to keep yourself right. We've got ten people who could do X, Y, or Z, but we would love to continue to evolve The Trail—especially around all the community and clan stuff around towns. There's some real crazy plans that we'd love to implement for that but it really depends on how fascinated the audience is.

There's a big following on mobile at the moment.

Yes, very much so. That's a global audience too—there's The Trail in the west, and there's going to be The Trail in China, there's going to be all sorts of evolutions of The Trail going forward, and then there's the thought of: should we continue to evolve or should we think about The Trail 2 or should we think about taking a section of The Trail and amplifying that up—it's head spinning the amount of opportunities that are there.

On that point is cross-play something you'd consider down the line?

Yeah, I'd love to do that although there are some tedious snags in doing that. There's some rules that Steam has and there's some rules that the App Store has and Google Play has that makes that somewhat challenging—to be able to buy content on one device and use it on another device. The actual mechanics of doing it is really simple. The Trail has a server, and this server keeps track of everyone in the world, millions of people in the world, and what they're doing, where they are and it's about matchmaking them together.

That gives you some real opportunities for doing cross-play. I think it would be very hard to balance a premium of The Trail against a free-to-play version, but that's not to say it isn't possible. An interesting opportunity going forward is working out whether or not you could compete, could you create a competition between free-to-play players and premium players—and I'm making this up now [laughs]. Here we are, I'm falling back into the old trap of designing the game while talking to the press! Let's not go any further with that.

In light your recent work, do you see yourself more as a mobile developer nowadays?

What I'm obsessing over today is more far more PC centred. I do love the attention to detail that you can give in a PC game. The bigger screen space is a lovely luxury, I can assure you. And of course the mouse is the greatest gaming device in my opinion. I'll always love the PC.

Most Popular