Our Verdict

Oddworld: Soulstorm's charm, characters, and sincere narrative are imprisoned within buggy, erratic software.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A 2D stealth puzzle game, and a reimagining of 1998's Oddworld: Abe's Exoddus.

Expect to pay: $50/£40

Developer: Oddworld Inhabitants

Publisher: Oddworld Inhabitants

Reviewed on: Windows 10, GeForce GTX 1070, Intel Core i7-9700 CPU, 16GB RAM

Multiplayer? No

Link: Epic Games Store

It's easy to root for Abe. The Mudokons, a mystic race of amphibian-like pacifists, have been enslaved for centuries by the cruel industrial cartels of the Glukkons. The cartels' greed is insidious, and it poisons everything on Oddworld. Mudokons are worked to the bone, institutionally drugged, and punished for any perceived insubordination. It's up to one Mudokon to spark an insurrection and free his people from chains. That's the plot of the 1998 Playstation cult classic Oddworld: Abe's Exoddus, and many of the same core story beats are preserved in this 2021 "reimagining." Lorne Lanning, patriarch of the Oddworld cosmology, has only grown more pointed in his depiction of capitalism's rot, and as usual, he uses a strange, off-kilter drama composed of nasal-throated aliens to get his point across.

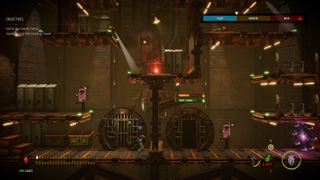

Veterans of Exoddus will recognize Soulstorm's basic rhythms from the jump. This remains a 2D stealth puzzle game in the traditions of Gunpoint, Mark of the Ninja, and the many other games that took initial influence from Oddworld all those years ago. Abe is a wimp; he can't really fight, nor can he absorb more than a quarter-clip of gunfire to his chest. Glukkon cronies crawl around the rickety, rust-stained scaffolding that make up most of Soulstorm's geometry, and Abe's best option is usually to sneak past the police unnoticed, or MacGyver together a few meager weapons. Perhaps you lay down a stun mine and make a beeline for the exit, or chuck an explosive can of soda at the feet of a thug before binding them up with a spindle of scotch tape.

That's the marquee new mechanic with Soulstorm. Like every other new game on the market in the 2020s, Oddworld possesses a crafting apparatus now. Abe skulks through dirty lockers, flickering vending machines, and rotting trash cans in order to accumulate a small trove of grubby, dystopian ephemera (empty bottles, sticks of bubblegum) that the player can hastily stitch together into deployable ammunition.

This makes every encounter a lot more modular than was possible on the PlayStation. A herd of ravenous guard dogs in the way? Just pull up the inventory menu and produce a few makeshift grenades. Soulstorm's forge system doesn't deviate far from the bare essentials—you're only looking at 11 recipes here—but players will spend a good amount of time opening their inventory to fire up the revolution.

Maybe Soulstorm is an ideal tribute to the PlayStation era, considering how much period-specific jank is in the code.

It's a good idea. Aesthetically, Oddworld always bridged the gap between facile, Saturday Morning Cartoon cheese and perturbing ultraviolence, and the idea of arming Abe with flaring molotov cocktails to clear the path towards deliverance is very much in theme. Unfortunately, Soulstorm's inventiveness is overshadowed by some jarring technical issues. I consistently ran into bugs that made the game far more frustrating than it should be.

In an early level, for example, Abe is tasked with evading an armada of snipers camped out on a distant ridge. Halfway through I needed to make a jump to a ladder, and found that I was immediately shot dead every single time I hurtled through the air. After trying and failing in dozens of different permutations (am I supposed to sprint? roll?), I eventually took to the internet to find that several other players were experiencing the same problem. The only remedy available was to restart the level entirely. Sure enough, that worked.

Maybe Soulstorm is an ideal tribute to the PlayStation era, considering how much period-specific jank is in the code. There were multiple times where the game's checkpointing system put me in the middle of an active firefight. I would die and respawn with hail of bullets inches away from Abe's tender, vulnerable head. Those mines I talked about earlier? Sometimes I'd throw them out only to watch them harmlessly levitate in mid-air. The collision detection on the monkey bars is maddeningly erratic; I've clipped straight through them on more than one occasion.

Those incidents are emblematic of a larger problem with Soulstorm's controls, which are slippery, floaty, and unreliable, all while simultaneously demanding razor sharp precision. Soulstorm retains Exoddus' difficulty, but there were many times that I didn't feel like I was truly equipped with the tools to succeed. It brought to mind other early console stealth games—those initial Splinter Cell titles in particular—where progression often arrived due to a happenstance subversion of the AI, rather than any of the player's personal ingenuity.

This problem worsens after Soulstorm kicks into high gear, and Abe is tasked with rescuing a legion of imprisoned Mudokons during his journey. You call out to them and they follow you in lockstep like lemmings. Ideally, Abe is supposed to bring them to one of the portals found in certain choke points on the map, but with no direct control other than a "Follow" and "Wait" action, I found that my rescue efforts were regularly doomed. There are times in this game where you're asked to herd a troop of Mudokons through tight corridors breached by whirring razorblades. One false step and they're all dead. In an early moment, as a Mudokon was following me, I jumped over a mine that was in the way. My squire did not mirror my actions; instead, he piled directly into the trap and died instantly. I am not some weathered Oddworld veteran, and maybe I don't understand the finer points of Mudokon corralling, but it didn't take long for me to write off these humanitarian efforts as a lost cause, and instead enjoy the viscera.

Oddworld has rarely looked more Oddworld.

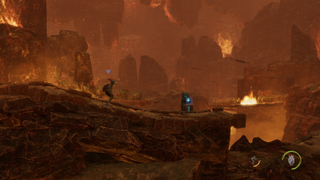

That's a shame, because the presentation of Soulstorm's story and characters is top notch. Oddworld has long been one of the great settings in videogames, and the Glukkons' bleak reign is extraordinarily vivid on modern machinery. The desolate strands of desert and steel, the horizon dotted with towering refineries belching inky blackness into the sky above—it's all perfect. Oddworld has rarely looked more Oddworld.

The same goes for the narrative, which takes a couple notable risks in how it alters some of Exoddus' motifs. In some ways, Soulstorm is a videogame about addiction, substance dependency, and the euphoria of what comes afterwards, which is territory rarely explored on PCs. All of this will likely strike a chord with Oddworld lifers, who may be willing to look past Soulstorm's more eccentric quirks. But as a casual appreciator of this universe, I spent a lot of my time with this game thinking about Lorne Lanning's long-gestating desire to make an Oddworld film. It's an attractive prospect: A new work from the talented Oddworld Inhabitants team, but without the bad collision detection.

Oddworld: Soulstorm's charm, characters, and sincere narrative are imprisoned within buggy, erratic software.

Luke Winkie is a freelance journalist and contributor to many publications, including PC Gamer, The New York Times, Gawker, Slate, and Mel Magazine. In between bouts of writing about Hearthstone, World of Warcraft and Twitch culture here on PC Gamer, Luke also publishes the newsletter On Posting. As a self-described "chronic poster," Luke has "spent hours deep-scrolling through surreptitious Likes tabs to uncover the root of intra-publication beef and broken down quote-tweet animosity like it’s Super Bowl tape." When he graduated from journalism school, he had no idea how bad it was going to get.