How Strange Horticulture's devs went from Flash to one of the best games of the year

The tragically lost world of Flash games made a fine training ground for indie developers.

Strange Horticulture sets you up to think it's another cozy game about running a shop—a puzzle game where you flick through your book of plants, examine the fungus and ferns and find the right medicinal herb or decorative flower for each customer. Slowly, as it goes on, Strange Horticulture trowels a layer of creeping dread over this wholesome setup. A narrative grows out of it, a story of mystery and ritual murder that plays out through the customers, no less strange than the horticulture, who keep returning to your shop.

Though Strange Horticulture didn't come completely out of nowhere, having a demo at Steam Next Fest in 2021 that made everyone's list of favorites, it was still a surprise just how good the finished game turned out to be. Chris Livingston gave it a score of 90 and called it "the best detective game I've played in years".

Development studio Bad Viking is two brothers, Rob and John Donkin, who actually have over a decade of development history behind them. Nobody noticed because almost all of it happened in the world of Flash games.

On an ancient internet without social media, with prohibitive download limits and legions of students with nothing better to do, websites like Newgrounds, Miniclip, Armor Games, and Kongregate were the places to go for free games. You didn't need a lightning-fast connection speed to play Line Rider or The Last Stand. And you didn't need to be an expert programmer to make one of your own. Rob Donkin was still a university student when he made Pondskater, a game about eating flies and dodging bees, collecting power-ups like a mounted machine gun to shoot bees with. In the cartoon games that dominated Flash, that kind of thing was pretty common.

"I had fun making it," Rob says, "and it was fun to be able to just release it and people would actually play it straight away, which you kind of can't do anymore. But that was the good old Flash days—you just chuck stuff online and people start playing it and tell you how silly it is."

His follow-up, Panda Tactical Sniper, was equally silly. "You were a sniper and the panda would tell you stuff to shoot. It was pretty weird, but people loved it. That was quite a successful game, and that got me a sponsorship. I suddenly realized, 'OK, you can earn money from this,' and went straight into doing that full-time out of uni."

Sponsorships meant adding a given web portal's branding to your game, usually a pre-loading logo and a "play more games" link that led to their site. For several years Flash sponsorships were a decent way to earn a living as a bedroom coder. When Rob's brother John lost his job in the film industry, Rob invited him to try his hand at game design too.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Their first joint release was The Adventures of Red, an adventure game where you solved puzzles on a quest for a chocolate muffin. It racked up a decent player count and suggested they made a good team. "We just sort of stuck with it and started making more Flash games and then set up our company together," John says. "We're still here 10 years later, which is remarkable really."

...we didn't really know how to put a game on mobile and have it grow organically

Rob Donkin

"In those days it was so much easier," Rob says. "Now, if you want to make money from games, starting out, I don't know how you do it because there isn't that model of 'make stuff in a couple of months, put something out there'."

Pondskater took only weeks to make, and even the more advanced games the two made together were completed and released quickly enough they could pay for themselves in a short amount of time. "There's nothing comparable really to that now," Rob goes on. "I guess you can look at the mobile market and, yes, you can churn stuff out quickly there, but to actually compete with anyone…"

Trowel and error

Bad Viking's first "big success" was Bad Eggs Online, a multiplayer game about eggs at war, "an artillery game based on Worms, essentially," John says. They followed it with a sequel for mobile, Bad Eggs Online 2, and despite Rob's comment about the difficulty of competing in the mobile market, John notes that people "are still people playing it to this day."

They were motivated to look at other platforms when, as Rob puts it, "the Flash game market started drying up." Adobe and Microsoft stopped supporting it at the end of 2020, and Chrome stopped supporting it at the start of 2021. Though the brothers could have continued making mobile games, they attribute the success of Bad Eggs Online 2 on phones to the fact the first game found an audience on Flash. "We brought them over to mobile and then it grew from that," Rob says,"but we didn't really know how to put a game on mobile and have it grow organically, or market it or anything like that."

What they knew was PC gaming, which also seemed like a perfect place to attempt something a little more ambitious. "I guess we wanted to do something a bit bigger as well," Rob says. "We wanted to try to handle a PC game for the Steam market, because we hadn't released anything on Steam." Their first attempt was another artillery game, this time with a straightforward military theme, called Broken Ground. "It was basically like Bad Eggs, but a bit more grown up."

It launched in April of 2018, and exactly five months later they announced they were shutting down the servers. Broken Ground was their first real failure. "We took what we'd learned from Bad Eggs and we tried to apply it to a Steam market," John says, "and the backlash there was huge. They don't like microtransactions." A free-to-play game, it featured weapon packs for sale, which made players accuse it of being 'pay-to-win'. "We tried to just make it variety-based, rather than 'you can buy overpowered weapons'. It wasn't like that, but people didn't see it that way."

The experience turned them off making another game in the same vein. "After Broken Ground we were very jaded with multiplayer in general," John says. "It's a lot of work. You don't get much positivity in the community. It's very toxic, is multiplayer."

"Especially competitive multiplayer," Rob adds. And so they made a singleplayer game instead. While Flash had been forgiving, with its low cost and short development times, now they were facing the dilemma common to indie developers: finding a project that would be creatively satisfying and sell enough to make it worthwhile. "If you look at the Venn diagram," Rob says, "you've got: what you would like to make; what you're capable of making; what your skill set says that you can make; and then what is gonna be commercially viable. The overlap of those is this tiny little dot in the middle."

Thyme for a change

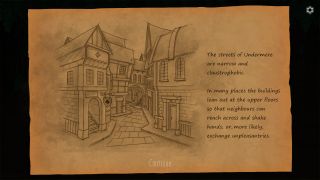

When I was playing Strange Horticulture, at first I thought it was taking place in a pseudo-Edwardian fantasy world. Some of the plants had magical properties, and the place names on the map, which you use to find new plants, seemed impossibly whimsical. I didn't realize it was a real part of England until an hour or so in. Turns out, Scafell Pike and Bootle are perfectly real locations in the Lake District—though Undermere is called Windermere in the real world.

I couldn't name half the flowers, well, 90% of the flowers in my garden

John Donkin

The area had personal significance for the brothers, being "a place which held a huge nostalgic appeal because that's where we went on holidays as kids," John says. "It's a beautifully romantic, rainy, green, lush, mountainous, strange and uplifting place. But also spooky, dark and mysterious at the same time, with the potential for fairies and goblins and all sorts."

"It's quite a magical place," Rob says. "In hindsight, it's obvious that people from other countries aren't gonna know the Lake District."

While they chose a setting they knew intimately, they paired it with a subject they didn't. "I couldn't name half the flowers, well, 90% of the flowers in my garden without looking them up on the internet," John admits. He struggles even to remember to water his houseplants. "They don't like to stay alive do they?" adds Rob, who doesn't have a green thumb either. "I need houseplants that need very minimal attention," his brother replies.

They were actually inspired by a book. Breverton's Complete Herbal: A Book of Remarkable Plants and Their Uses, which modernized the work of 17th century botanist Nicholas Culpeper. Both of the brothers have copies near at hand. "We just found this in a library one day and were like, gosh, how good is this?" says John. "It's got all these cool plants and they've all got these amazing weird properties and uses. Some for I guess witchy things, others more as medicinal things. It's just so inspiring. We just thought, well, let's do that, but make them a bit more magical."

Strange Horticulture's plants are fictional, though names like Bishop's Parasol, Farmer's Worry, and Gilded Dendra evoke real herbs. "The main reason we didn't do real plants is that we needed more control over exactly what they looked like," Rob explains. Inventing plants meant they could ensure each puzzle only has one solution—even if sometimes plants are deliberately similar enough to make you think twice.

Say aloe to my little friend

Strange Horticulture's story has a structure anyone who has played a tabletop RPG will probably find familiar. It's oddly common in RPGs for players to fixate on the act of shopping, and if an NPC shopkeeper interests them they'll return to their shop time and again. (Entire episodes of Critical Role have ended up being devoted to shopping trips because the store-owners had personality quirks the players enjoyed.) Strange Horticulture reminded me specifically of Call of Cthulhu, an RPG where paranormal investigators uncover cults and foil rituals. Only while the investigators are off having their adventure, we see it through the eyes of a shopkeeper they keep visiting to ask about a specific poison or the mystical properties of whatever herb they found at a crime scene.

"People are coming from this grander story happening all around you and you're just sitting in your cozy shop with your cat," John sums it up. "You're sort of interfering with the story and can nudge it in certain directions, but ultimately, yeah, you're that NPC."

Hellebore, the aforementioned cat in your cozy shop, seems like a vital and obvious element, but was only added late in development. The two were discussing what a particular character could do that would suggest they were a bad person. "We had this idea of them doing something to a cat," John says, before Rob interrupts. "Hang on, I'm staying out of this. You had this idea."

"We were just discussing ideas!" his brother replies. "Anyway, that's the first time we mentioned a cat and almost immediately we decided, 'Well, of course this shop has a cat. Yeah, the cat owns the shop almost.' It made absolute sense, and it was like the gel that brought everything together."

The kooky shop with a resident animal is definitely a thing. I used to live not far from a bookstore whose cat had a permanent home in the window display, and now I'm near a second-hand clothes shop where customers have to step over two dogs who sleep in the aisles. "It's kind of a witchy game as well," says Rob, "so it seems pretty obvious that it was going to be a black cat."

With Hellebore and other final touches, Strange Horticulture was released in January, 2022. The early feedback was so positive that Rob describes it as "uplifting". His brother points out, "The difference between releasing a multiplayer game, all the emails of people just moaning about stuff, and the almost overwhelming positivity that Strange Horticulture has gotten—for motivation, for mental wellbeing, for everything, it's just so much nicer to be on that side of it."

We certainly didn't expect it to have done as well as it has

John Donkin

"Which is not to say that 'oh, yeah, singleplayer games are all happy and rosy, everyone gets nice feedback,'" Rob says. "Like, we know that's not the case. We're very lucky to be in this position."

Strange Horticulture's varied puzzles and hint system may have benefited from the brothers' background making Flash adventures, but it's such a step up from Bad Viking's previous releases you wouldn't know their history was in Flash if I hadn't told you. With its desk full of books, notes, and informative letters to keep track of, Strange Horticulture feels more like part of the tradition of UI games like Papers, Please, or the kind of brain-bending board game that comes in a box full of booklets and maps like Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective. It was a territory far away from anything Bad Viking had released before.

"We honestly had no idea how strange Horticulture was gonna be received when we launched it," says John. "We certainly didn't expect it to have done as well as it has. When it got to I think 120 reviews on Steam without a negative one, we were just like, 'This doesn't happen to us. Is the game that good? We like it and everything, but can't believe this many other people like the game.'"

"Our mum liked it," says Rob.

"That was it. My wife liked it, Mum liked it, that's the feedback we'd had."

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.

Most Popular