How Gwent became a competitive card game with singleplayer campaigns

“Don’t forget, we’re CD Projekt Red”

Gwent wasn’t even part of the plan. Originally created by a pair of designers at CD Projekt Red in their spare time, Gwent eventually found its way into The Witcher 3 and became a small phenomenon: the mini-game that was so good, it just had to find life beyond The Witcher 3. A few months after The Witcher 3 was released, CD Projekt was still being flooded with emails about the card game. Lead designer Damien Monnier, one of Gwent’s co-creators, took those emails to the leadership. They asked if it was possible to make a standalone game. A multiplayer game. Of course he said yes.

But how would they do it? The easy path, and the path I expected them to take, was a simple rebalancing of the cards in The Witcher 3, aimed at turning the single-player progression into a decent competitive game. I figured it would hit PC and smartphones as free-to-play game. But that was just a starting point for Monnier.

“Okay, but what if you don’t want to play online?” he said. “Many people don’t want to play online, but still want to enjoy Gwent again. Let’s create a single player campaign. Let’s get the lead writer from Witcher, let’s get the lead quest designer from Witcher, let’s do a proper thing. And then they came on and said, ‘well what about if you explore this map and you’re able to interact with things around the world, and the way you interact will have consequences?’ And it just snowballed into this huge thing. We’re looking at, like, ten hours, but ten hours for [just] one campaign.”

Gwent’s singleplayer campaigns look to essentially be card battle RPGs—imagine Puzzle Quest, but with gorgeously illustrated 2D cutscenes and stories and quests written by The Witcher 3’s leads. The E3 presentation I saw had Geralt on a quest to protect a young princess. The characters in the campaign (Geralt, the princess’s guardian, and his retinue of men) actually make up your deck. The 2D top-down world map you walk around to discover events and progress the campaign looks storybook-esque, and it’s going to prompt some familiar Witcher 3 choices—to save someone or not, to investigate a mystery or leave well enough alone—that will affect the outcome of the story.

We’re looking at, like, ten hours, but ten hours for [just] one campaign.

Damien Monnier, Lead designer

In other words, it sounds a whole lot like The Witcher 3, minus the 3D engine. And with card combat instead of swords.

“There’s set choices and consequences, cards that you can receive from them, and that's the whole point,” Monnier said. “You start with a base deck and as you progress through the campaign, it gets bigger and bigger.

“I mean there’s loads of stuff that’s happening. You have these cool comic-like panels that appear where you [make a choice], as you choose you get to see a preview of what could happen....It’s just a little thing, but [our focus on quality] reflects in these little things when someone says, ‘wouldn't it be cool if?’ And we say, ‘well actually yeah, you’re right, it would be. How long would it take to do it?’ There’s a lot of people working extra time because they want to. We work super hard. I’ve been making games for over a decade now, and I’ve never been surrounded by such hard-working, crazy people.”

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

CD Projekt isn’t talking about how many of those campaigns it will make for Gwent or how much they’ll cost, but they’re the part I’m truly excited about. 10 hours gives a campaign enough meat to offer a sense of progression—starting with weaker cards, collecting heroes and rares along the way to bolster your deck—that I found addicting in The Witcher 3. And I expect battles against the AI to benefit from the complete rework Gwent has seen to be a viable multiplayer game, which is free to play in the vein of Hearthstone.

“Every step that we took we questioned how the standard for free-to-play was the right way for us, because unfortunately F2P has this bad image,” Monnier said. “Marcin Iwiński, [CD Projekt’s] co-founder once said to us: ‘guys, don’t forget, we’re CD Projekt Red.’ So that meant a lot.”

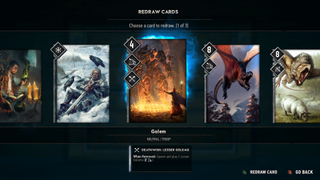

Monnier gave me an example of what being CD Projekt Red means when developing a free-to-play game. When you buy a pack of cards, either with real money or in-game currency, you’re guaranteed to see three cards that are rare or above (rare, epic, or legendary). You pick one, and get four more random cards. "We say okay, if you want to spend money, that’s fine, but we want to do more than just here’s five random cards. We want to say here’s four random and here’s one you can pick.”

“At the same time, we don’t want these guys necessarily get an advantage over people that don’t want to spend money, and also we don’t want people to grind to be able to get card packs,” Monnier said. “And that’s something I’m not going to tell you about yet because we want to see people’s reaction, but we’ve worked on this system that we think has cracked it, where you can still totally be competitive without having to spend money, and the goal for us is that if you feel that you want to spend some money, go ahead, but at no point will the game tell you this is it, you hit a wall, you must spend money.”

I only got to play a single game of the new Gwent, and I mostly liked what I saw. The card and board art have been completely revamped, and while I think the cards are gorgeous, the table is almost too visually busy, covered with numbers and symbols. They’re all functional, but I wouldn’t mind a cleaner interface with smaller (or fewer) icons. I think that after a few minutes of play, most people will be able to remember what kinds of cards go where.

The new types of cards I encountered were interesting—there are now units that get buffed by weather effects instead of debuffed, and are actually cleared off the board (or automatically summoned) when you play a weather card. I haven’t played nearly enough to know how balanced Gwent will be as a competitive game, but according to Monnier, designing a smart free-to-play system was harder than designing for balance.

At no point will the game tell you this is it, you hit a wall, you must spend money.

Damien Monnier, Lead designer

“What we would deem superior decks don’t necessarily win a game,” he said. “It’s often based on the player’s skills...personally, I’m really happy with it. The first step for us with this alpha is introducing the player and the human element. It’s important that you feel it when someone is across the world and you’re playing against them. So right now you can see what the opponent is looking at, you can see if he or she is looking at his hand, looking at maybe when you place a card, you can see his highlight bring the card up…[you] can see when the player is looking into your graveyard, you can see when they’re looking into their graveyard. Why are they doing that? Is it because they’re going to play a gravedigger they can steal from your graveyard? Maybe it’s in your best interest to grab your stuff from there [first]?”

Gwent will be available in a closed beta starting in September, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see some big changes by the time it goes into wide release. “The players who asked for this will be the judge of it, and they will tell us if we managed to pull it off,” Monnier said. “Personally I’d say yes, I still have a blast playing the game, but it’s a game for the fans and the fans will tell us.”

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).

Most Popular