How comic-book noir game Framed makes great chases and escapes

The noir comic book puzzles of the Framed games made it to PC as the Framed Collection.

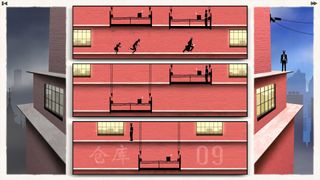

Framed is more than the sum of its obvious parts. It's an interactive comic book spy chase, but also a meditation on design, game clichés, and ambient storytelling. A subtle exploration of evasion and escape emerges from a simple premise: you control the order and sometimes orientation of comic book panels and the characters make independent decisions as they run through them. Do they sneak or incapacitate an enemy? Where will the red door, or blue corridor, lead to next?

I asked game designer Joshua Boggs if he'd considered a different theme. "We played around with the idea of superheroes fighting," he says, "or trying to perform an action, or feat. We also had an investigative prototype, with the main character working through clues in a murder scene, but that proved too slow. The 'chase'' theme worked best for game mechanics and narrative, as it drove the action forward and made for hectic/fun situations to escape from."

One of the nameless protagonists, the Sunglasses Guy, 'borrows' a bike in an early level of Framed 2. He's being chased by a dog who runs faster than he does and, although the bike will obviously help, he needs a moment to climb on. A solution requires being able to visualize how many panels it will take the dog to catch him. In the next level, he needs to land a jump on the bike and, given you can't direct him to ride faster, you need to see how the panels might be arranged to create momentum. Other clues, like skid marks, show how he might take corners.

There were a couple of really fiendish levels we had to cut, like Plank Hell, which saw you having to navigate two characters between collapsing panels

Ollie Browne

When I ask the developers' favorite levels, game designer Stu Lloyd cites, "The one we call Dog, Cat and Cops, in which the cat can create a range of distractions, some of which aren't actually helpful. Usually, the reusable panel levels (where players must progress through a panel more than once) are the ones providing the most challenge. The Dog, Cat and Cops level is simple, yet misleading. We encourage experimenting, to discover that what you think may happen may not, then to work backwards to solve it."

Framed challenges your expectations of how characters will behave. They don't always do what you’d have them do, but controlling context instead is intriguing. Unpredictability underscores the stressfulness of chase scenes too, with characters perhaps choosing a different door to escape out of depending which angle they've approached the panel from.

Characters, cops, and objects like drainpipes can behave in several, completely different ways In a single panel depending on how its ordered. How do the designers account for all of the potential combinations? Boggs says, "We test concepts in silly, paper prototypes (literally stick-people, drawn on paper). If this works, we look at refining it and including it as a scene. We try to be inventive and consider the different possible ways there are to change the context of the action and space in which the character can move."

Artist Ollie Browne adds, "There were a couple of really fiendish levels we had to cut, like Plank Hell, which saw you having to navigate two characters between collapsing panels, through tall buildings. The paper prototype was fun, but we realized there were literally hundreds of animations needed and it would've taken us months." The animations are important, sometimes adding humor to a chase, like when a factory arm removes the box that was hiding the Sunglasses Guy, and imparting information, like suggesting one character is heavier or stronger than another.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Replaying these, I noticed how coherent and evocative the backdrops are, too. In the Dogs, Cats and Cops level, there's a clock tower in the distance, which is visited later. Sometimes clouds or buildings will line up to provide a clue or mislead you as to the alignment of panels, like how artworks in Gorogoa could fold in on themselves, matching elements together in various ways.

The setting supports the theme, Browne says, "From a narrative perspective, where are the characters and why? Given it's a noir game, cool, moody backdrops suit it well, too. Possibly the most important aspect was that there isn't a lot of screen space for each panel of content. We had to be careful that the backdrops were simple enough to read, but also detailed enough that they could set the scene and be alluring to the player. So, simple things like giant moons, distant rooftops and neon are all iconic noir imagery that are easy for the eye to read."

The silhouetted characters and the intentional lack of text dialogue also allows the player to bring their own imagination and perspective to the story.

Joshua Boggs

It's exciting to escape through rickety building sites, or to scale crumbling walls. At one point, my characters became the pursuers themselves, which was a neat touch. Given how much of Framed 2 relates to timing, with cooldowns on reusable panels and the action unfolding at varying speeds, setting the climactic scenes in a clock tower seemed especially appropriate.

"This is a game that transcends a lot of the language barriers you would find in more traditional narratives," Boggs says. "Because the world, the characters and their gestures form the narrative, it can be interpreted by anyone. The silhouetted characters and the intentional lack of text dialogue also allows the player to bring their own imagination and perspective to the story." At one point, the Flower-Hat Lady stares at the camera and her face is a black oval. It was a reminder that she was never actually 'me' or 'mine', an inscrutable character who I couldn't trust to take the right exit from a network of vents.

Another unusual consequence of indirect character control is that sound effects don't need to provide time-sensitive information to players. So, when officers fire guns, it's as if the drummer improvises additional hits. I love the idea that an accompanying jazz combo is engaging with the action, like in a play.

A particularly elegant feature of the music's implementation occurs when additional textural layers are faded in on pressing play. If your planning phase was drums and saxophone, they might be joined by synth countermelodies as the character starts to move through the level. Musical embellishments, like a countermelody in bells on a level where the girl rings a giant bell, are everywhere.

"Certainly, the biggest challenge was to integrate the two games into one collection," Boggs says, "so we needed UI love and specific level select menus for each of the games. Our main PC programmer, Tristan Lewis, spent a lot of time perfecting and polishing, ensuring the game could be satisfying when played with a mouse, keyboard or controller. We also worked with The Machine QA to make sure that the whole experience delivered on the high-quality players have come to expect from these games."

You worry about how people will receive a project you put a lot of yourself into. It's even scarier to bring a game from mobile to PC.

Joshua Boggs

Although the Framed Collection isn't incredibly challenging (and I probably cracked the games in two hours, total), Framed 2 is not the kind of game I could play on the train—at least, not while also expecting to get off at the correct station. Problem solving in multiple, visual steps is best done with an office chair and a coffee, in my opinion (on PC). Usually, when I'm stumped by a puzzle game, a little break helps immensely. With Framed, even a momentary diversion puts me back to square one, particularly for the levels with reusable panels.

I also tend to notice design more when I'm playing on PC, and this is surely a game for game designers. I ask Boggs how he feels about bringing Framed to a new (although always intended) audience. "It is scary, always," he says. "You worry about how people will receive a project you put a lot of yourself into. It's even scarier to bring a game from mobile to PC. But we wanted to bring it to PC and to try to make it as accessible to as many people as possible. Our players frequently asked us to bring the game to more platforms."

As an exploration of escape/chase scenes and context-driven game design, Framed is a revelation. I read comics when I was a kid. But why didn't I consider rearranging them, chopping them up and giving them to people as puzzles? It seems like such an obvious thing to do. Often, the most interesting games are the ones that you would never have thought to devise yourself, but innately understand when you play them. It makes sense the Sunglasses Guy is going to break the plank if he hits it from a great height—I just need to figure out how to ensure his path to the plank takes him lower.

Most Popular