How greedy microtransactions sparked EVE Online's disastrous Summer of Rage

This exclusive excerpt from Empires of EVE: Volume 2 recounts the 2011 in-game protests that brought CCP Games to its knees.

Conflict is etched into the very heart of EVE Online. On any given day, thousands of players war against one another as its player-run alliances clash over key star systems and resources. But one of EVE Online's most disastrous conflicts happened in 2011, when a series of bad development decisions led to in-game protests of an unprecedented scale that, to this day, remain a bitter memory for EVE Online's long-time pilots. Those few destructive months became known as EVE Online's Summer of Rage.

You can find out more information about Empires of EVE: Volume 2 on its official website.

Andrew Groen is an EVE Online historian who has turned its endless conflicts and bitter betrayals into a series of books that chart EVE Online's violent in-game history. The first book, Empires of EVE, explored EVE Online's earliest conflicts from its launch in 2003 through to the conclusion of The Great War, which cemented player-run alliances like Goonswarm has one of New Eden's foremost superpowers. In Empires of EVE: Volume 2, which released on May 25, Groen retells the biggest stories of EVE Online's modern era.

In this exclusive transcript taken from the middle of Volume 2, Groen recounts the giant missteps by CCP Games that led to widespread in-game protests in the summer of 2011, the ripples of which are still felt in EVE to this day.

The Summer of Rage

In 2011, EVE Online was reaching the peak of a quiet ascension. The number of players subscribed and involved in the community had been growing steadily since 2003, but that pace had quickened dramatically in 2005 and kept up at a brisk pace of growth through to 2010, when the persistent rise finally began to reach a high plateau. EVE Online made global news as its population grew past that of Iceland, its mother nation.

The main metric the community uses to gauge the health of the game is called "Average Concurrent Users" which is the average of how many accounts are logged-in to EVE Online at any given time throughout a month. In January 2011, EVE reached its highest ever ACU—roughly 60,000 people online in New Eden at any given time—and the company was in the midst of a celebration of its vision for EVE.

The main player hub in EVE for that massive concentration of players was the trading hub "Jita" or more specifically, the "Caldari Navy Assembly Plant" orbiting the fourth moon of Jita's fourth planet.

Whether its haters like it or not, under Jita's wrist is the pulse of New Eden.

Andrew Groen

Jita is the most famous system in EVE Online, and has been essentially since the game's founding. Jita is a place unlike any other in EVE. It was organically chosen by the players to become the market hub of EVE Online due entirely to its natural geography, home to a space station owned by one of the game's NPC factions where players can buy and sell goods.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Perhaps appropriately, Jita is also utterly reviled, even by EVE's own players. It's the center of New Eden's industry and commerce, and it's usually the most populous star system. Many—if not most—of New Eden's 7500 star systems are often nearly vacant, but Jita’s status as the player market hub means it is routinely filled with thousands of players. Precisely because of that, it's also absolutely rife with scammers and bots. All of that traffic, scheming, and harassment makes it into a place that is bustling, thriving, conniving, and singularly despised. In other words, no other place is quite so quintessentially EVE. Whether its haters like it or not, under Jita's wrist is the pulse of New Eden.

EVE Online was no longer the plucky Icelandic social experiment from 2003. Now it was one of the biggest products in the video game industry, with more than 500,000 subscribers bringing in millions of dollars per month for a growing online gaming company with global ambitions.

CCP Games' ambition to create a virtual space that survived for decades was starting to seem downright practical, and Jita was its capital. The company even began using the phrase "EVE Forever" as a tagline in advertisements, a nod to the mostly-serious idea that EVE could become the first virtual space to achieve actual permanence and never be shut down.

As EVE Online grew and grew, the player community was united in celebration with CCP. The relationship between CCP and the community had been badly damaged by the "T20 scandal" of 2007 in which a developer (who went by the name "T20") was found to be cheating. But as time rolled on and the game continued to grow, the two sides remembered that their fates were linked, and the players again began to see success for CCP as success for EVE.

However, as we will see in this chapter, business decisions made in Reykjavik, Iceland soon spurred mass protests in the Jita star system within EVE Online. It all began with a single phrase that launched a mass community rebellion:

"Greed is good?"

Ambition

As EVE’s player base expanded, so did the developers’ vision for the game.

Iceland—the home country of CCP Games—was, in the late 2000s, recovering from literally the worst banking crash in the history of economics. To make matters worse, in early 2010, the tiny island’s volcano Eyjafjallajokull (pron: eya-fyatla-yoktl) erupted, shouting 750 tons of magma per second into the sky, blanketing the country and half the continent of Europe in ash, and disrupting economies and air travel systems.

When CCP Games looked inside its servers it saw a virtual world that was somehow more financially stable, less volcanic, and if you could believe it, more populous than Iceland.

Not only was EVE Online becoming one of the most enviable products in the gaming industry, with the most unique player experiences; from the perspective of CCP, EVE looked like the future of humanity itself. Even as the world literally melted down around them, CCP Games presided over eight years of year-over-year growth for EVE.

The core of the company was a group of people whose most outlandish and optimistic idea of the late-90s (EVE Online) had not only succeeded but had become a roaring global success worth hundreds of millions of dollars. What do you dream of when you're already living in your dream world? As EVE’s player base expanded, so did the developers’ vision for the game.

In the late 2000s, CCP dreamed of building not only an entire suite of films and television shows based on the player stories you're reading in this book, but also an entire ecosystem of EVE-based games that linked together into a single virtual multiverse. One day, CCP hoped, players would be able to grab a joystick and fly as a fighter pilot in a first-person starship simulation (EVE: Valkyrie) in battles led by fleet commanders playing EVE Online, and then dock their ships in their newly conquered space station, meet each other at a bar as their avatars and then streak down from orbit to the surface of a planet to a first-person shooter battle happening on the ground (DUST 514) to fight for control of a defense platform which would actually affect another battle somewhere in EVE. CCP envisioned a future in which EVE organizations were sending strike forces into other video games to better control the ebb and flow of power in EVE Online.

It was a daring and expensive vision, and even with EVE Online bringing in tens of millions of dollars per year CCP needed to find opportunities to make more money by bringing new services to the players.

The other trend occurring at this time that heavily affects this story is the increasing prevalence of the sale of virtual goods in online games. Prior to ~2010, the vast majority of online video games used one of two business models: 1) the subscription model, which charged users a monthly fee for continued access to the game, and 2) the pay-up-front model which gave users free access to the servers once they'd paid the initial purchase price. EVE used both. However, around this time several popular games began to support themselves through the sale of virtual items like avatar clothing and consumable buffs.

Gaming communities—where vicious arguments over game balance are basically constant—worried that greedy corporations wanted to sell gameplay advantages to rich players. In the worst cases, it was obvious that certain companies had used gameplay design itself as a subtle psychological hook to keep players paying up.

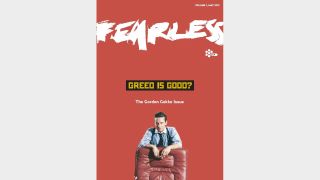

Inside CCP Games, a debate arose about how this new model might interact with EVE. Like a lot of large companies, CCP published a company-wide newsletter to help keep the company's employees on the same page. Called "Fearless," this newsletter was a platform for company debates and impassioned op-eds advocating for changes in strategy. In the May 2011 issue, Fearless featured a striking, deep red cover page adorned with nothing but the image of ultra-capitalist villain Gordan Gekko propped up against his signature 80's leather power chair. Above his head read the bolded words "Greed is Good?"

The theme of the issue was the monetization of virtual goods, and the Letter from the Editor kicked off the discussion:

"As EVE edges closer to being the grand dame of gaming, turning 8 years old this month, and our other titles continue their prodigious growth our development roadmap is shaping up stronger and better," reads the May 2011 issue of Fearless.

"However," the editorial continues, "as a subscription-based Golden Goose, EVE needs to incorporate the virtual goods sales model to allow for further revenue—revenue to fund our other titles, revenue for its developer: you."

What was being proposed was that EVE Online should become one of the only games in the world to use all three major online gaming business models at the same time. Not only did EVE Online cost money to download, it also cost a $15 monthly fee, and the company now wanted to introduce a new series of cosmetic character items that were gated behind a paywall.

All eyes focused on the impending release of the next EVE Online expansion which was the thesis statement for CCP's vision for the future of EVE: "Incarna," from the Latin for "flesh."

World of Darkness

The Incarna expansion was to be the fulfillment of a longstanding dream of CCP Games. Because EVE Online is famously difficult for new players to grasp, the company had long sought to make EVE Online more accessible and understandable to the average person. One of the big problems, they believed, was that average gamers don't want to play as a spaceship. CCP believed they wanted to play as an avatar who pilots a spaceship. It was a subtle semantic difference with enormous design and production implications.

Their solution and vision for the future of EVE Online was the "walking in stations" feature. Previously, EVE players' avatars were little more than a small picture in the corner of their user interface. With Incarna, CCP spoke of a dream for EVE in which players could dock their ships and walk around a personal space called their Captain's Quarters, or even "ambulate" around major stations like Jita 4-4 and encounter other players at shops, bars, and meeting places. In the most far-flung visions, it might even be possible for players and mercenaries to assassinate one another in these public spaces.

"Although EVE Online was CCP’s flagship product, the company was also in development of an avatar-based vampire MMO known as World of Darkness, as well as a ground-based first-person shooter known as DUST 514," wrote EVE journalist Matterall in a retrospective. "Rather than use an existing game engine, CCP began to develop its own proprietary graphics engine known as Carbon to power these avatar-based games. Carbon would also be the engine used to develop EVE’s planned expansion into avatar-based game play."

The development of Incarna takes place parallel to many of the events of this book, and had been unfolding for years already. It was first announced all the way back in 2007—four years prior—and had become just another promised feature on the development backlog.

Many EVE players saw this as an open backstab, given that EVE had always been a PC-only experience.

As the expansion edged closer to release, CCP Games journeyed to the Electronic Entertainment Expo—at the time the biggest event of the year in gaming—to reveal its multi-game vision for EVE, focusing on the first public information about its first-person shooter game DUST 514.

However, there was a perplexing detail in their presentation that caught the EVE community completely off-guard, and it would eventually cascade into a full-on public relations crisis that forced CCP Games to layoff one in five employees:

CCP announced that DUST 514 would be a console exclusive. Available only on Sony's Playstation 3 platform.

Play B3yond

Many EVE players saw this as an open backstab, given that EVE had always been a PC-only experience. They saw a nakedly ambitious move by CCP to try to draw millions of "console gamers" into EVE Online. Many in the EVE community were perplexed and enraged to find that the game intended to expand their community's experience was in fact not playable by a large portion of them who didn't own the console.

Thousands of EVE players voiced their discontent on the forums and early social media...all at once. It happened so quickly that at first CCP didn't fully understand what it was dealing with: the opening stages of a full-on community revolt. CCP thought these were run-of-the-mill forum controversies that would run out of gas in a couple of days.

If you look at the Average Concurrent Users for EVE Online there is almost always a boost in player activity after a new expansion debuts as players reactivate their accounts to experience all the new stuff with their friends. But after Incarna there was a net decrease as disappointment gripped the community instantly.

The expansion which had consumed years of EVE Online development time was a massive disappointment. Promised features were missing, and the ones that were included often came with ironic catches. When players docked their ships in a station they would now appear inside the station as an avatar. Except the space you could move around in was a static room of only about 10x15 feet, and was skinned as a rusty Minmatar (one of the game's lore races) station no matter where you were in space. It also lagged badly, caused equipment failures in some players' machines, and inherently removed many EVE players' favorite pastime: looking at their ships in their hangar. Now, instead of looking at their beautiful ships they were cursed to the inside of a bland, lonely, rusty metal prison cell populated only by an avatar they had never seen before and thus had no emotional connection to.

When players did the math they realized that the going rate for the eyepiece when translated to USD was an astounding $70.

Andrew Groen

The other feature that had launched in the first wave of Incarna was the Noble Exchange or "NeX Store" which was essentially a digital shop for players to augment their new player avatar with vanity cosmetic items like jackets, boots, sunglasses, and a curious little item that ended up making enormous waves: a metal monocle.

The cybernetic monocle could be purchased with a new in-game currency called "Aurum," but when players did the math they realized that the going rate for the eyepiece when translated to USD was an astounding $70. In modern times we know these are textbook conditions for an internet community revolt, but CCP was ahead of its time, and did not yet have the benefit of history. The stage was set for what would become "Monoclegate."

"It didn't take long for people to realise that something was fundamentally wrong with the prices on the Noble Exchange," wrote Brendon Drain for Massively.com, a publication that covers online role-playing games. "At around $40 for a basic shirt, $25 for boots, and $70 or more for the fabled monocle, items in the Noble Exchange were priced higher than their-real life counterparts."

"Given the fact that player avatars could ambulate no farther than the Captain’s Quarters, these overpriced items looked like a cash grab by the company," wrote Matterall in a retrospective. "Overall, Incarna was a colossal disappointment after years of hype and mismanaged player expectations. The mood of the playerbase shifted rapidly from frustration to outright disgust."

The following day the controversy within the community reached an even more fevered pitch. On June 22, amid all the community furor, somebody inside CCP Games leaked the May 2011 issue of Fearless on the backchannel forum Kugutsumen.com.

"The Day EVE Online Died"

The hardcore fan community exploded with fear and skepticism about the future of EVE Online, with many leaping to the conclusion that this was a death knell for EVE as CCP would inevitably slip into the same shady business practices that had been seen in many other contemporary games.

For the first time, the wider community was able to read along with CCP discussions, and gain an understanding of how the company viewed and discussed issues internally.

The players had little context for the purpose of the corporate newsletter. CCPers say that its purpose was mainly to foster discussion within the company about key issues and at times play devil's advocate to explore controversial points of view, the kind of thing Icelanders take pride in. However, the popular perception abroad was that this was a glimpse into CCP's secret psyche, a greed wart that it had hidden from the players for years and allowed to fester.

Developers tried to soothe fears, but ended up only contributing to the utter disaster that was unfolding. Senior Producer "CCP Zulu" wrote a developer blog to address player complaints.

"This week has seen quite a controversy unfold," Zulu wrote. "In almost the same instant as we deployed Incarna—which by the way is one of our more smooth and successful expansions, not to mention absolutely gorgeous—an internal newsletter with rather controversial topics addressed leaked out. To further compound the confusion there was a clear and rather large gap in virtual goods pricing expectation and reality with a large segment of the community."

"While it‘s perfectly fine to disagree and attack CCP over policies or actions we take," Zulu continued, "we think it‘s not cool how individuals that work here have been called out and dragged through the mud due to something they wrote in the internal company newsletter. Seriously, these people were doing their jobs and do not deserve the hate and shitstorm being pointed at them."

Unfortunately, CCP Zulu's impassioned plea to spare the average employee of CCP Games fell on deaf ears as some players instead focused on comments he made in the blog which exacerbated the situation. In particular, the community was ruffled because CCP Zulu compared the $70 digital monocle to a pair of $1000 vanity jeans from a Japanese boutique.

The blog closed with a defiant statement that it was likely CCP would later introduce a variety of items for sale that were both more affordable and more expensive than what was currently available.

To make matters much, much worse a defiant all-company email from CCP Games CEO Hilmar Veigar Pétursson was then leaked online in which he urged employees to ignore the outcry.

"sent by hilmar to ccp global list

We live in interesting times; in fact CCP is the kind of company that if things get repetitive we instinctively crank it up a notch. That, we certainly have done this week. First off we have Incarna, an amazing technological and artistic achievement. A vision from years ago realized to a point that no one could have [imagined] but a few months ago. It rolls out without a hitch, is in some cases faster than what we had before, this is the pinnacle of professional achievement.

For all the noise in the channel we should all stand proud, years from now this is what people will remember.

But we have done more, not only have we redefined the production quality one can apply to virtual worlds with the beautiful Incarna but we have also defined what it really means to make virtual reality more meaningful than real life when it comes to launching our new virtual goods currency, Aurum.

Naturally, we have caught the attention of the world. Only a few weeks ago we revealed more information about DUST 514 and now we have done it again by committing to our core purpose as a company by redefining assumptions. After 40 hours we have already sold 52 monocles, generating more revenue than any of the other items in the store. [...]

Currently we are seeing _very predictable feedback_ on what we are doing. Having the perspective of having done this for a decade, I can tell you that this is one of the moments where we look at what our players do and less of what they say. Innovation takes time to set in and the predictable reaction is always to resist change. [...]

All that said, I couldn’t be prouder of what we have accomplished as a company, changing the world is hard and we are doing it as so many times before! Stay the course, we have done this many times before."

— Hilmar Veigar Pétursson, CEO, CCP

June 23, 2011

Thousands of players deactivated their alternate accounts in a show of protest.

Like the straw that broke the camel's back, the EVE community collapsed into what felt like open revolt. Within hours pilots began organizing outside the Caldari Navy Assembly Plant in Jita 4-4. Soon after, they got the idea to orbit the famous Jita Memorial statue nearby to better attract attention.

What followed was perhaps the greatest achievement in the history of the oldest of online gaming traditions: the spontaneous conga line. The protestors' massive conga stretched around the years-old statue like a great wheel. The spokes of that wheel were the lasers and missiles they fired at the statue—erected to honor the winners of a riddle contest years earlier. Though it was an aggressive display, the monument itself wasn't a destructible object so the only effect was a beautiful cacophony of colors and particle effects lighting up the skies of Jita. The ordinarily sturdy Jita supercomputer server hardware lagged under the strain as thousands of players undocked to join the great conga line orbiting the stationary 3D model of a robed old man gesturing to the stars.

But players weren't just protesting with their virtual lasers, they were also using their cash. Thousands of players deactivated their alternate accounts in a show of protest. While ordinarily a new expansion should entice thousands more players, instead onlookers were scared off from trying EVE at all as this increasingly looked like a virtual world on the brink of collapse. Yet no one could look away, because once again something was happening in EVE Online that nobody had ever seen before. Protests had happened in many online worlds by now, but never on this scale, and never with such splendid screenshots.

"The Council of Stellar Management is being flown to Iceland to discuss the issue in an emergency meeting, and I seriously hope that something good comes out of it," wrote EVE reporter Brendan Drain in an article on June 26, 2011. "I don't want to look back on this weekend in years to come and say to people, 'This was the day that EVE Online died.'"

Stellar Management

To attempt to quell the controversy, CCP called a special meeting of the player-elected Council of Stellar Management to hear the voices of the players and begin to understand how things had gone so very wrong.

For two days from June 30-July 1, the CSM was in the CCP Reykjavik offices involved in intense negotiations. Previous CSMs served mostly at the pleasure of CCP Games, but this time the council knew it had real leverage to not only enforce changes to the game but also to advance the station of the CSM itself and make it a more indispensable institution. The CSM this year was a Who's Who of nullsec leadership featuring not only The Mittani as its Chairman, but also Elise Randolph of Pandemic Legion, Death, Draco Liasa of RAZOR Alliance, and Goonswarm diplomat Vile Rat. At the end of the all-night session both parties agreed that the negotiations had been intense and fraught yet fruitful.

Even as protesters continued to swarm the monument in Jita 4-4 CCP Zulu appeared in a joint video statement with the Chairman of the CSM (The Mittani) to address the community and hopefully quell the unrest. Taken in context, the resulting video is one of the more fascinating artifacts of EVE Online's history. Two members of the EVE community—one who worked his way up through CCP Games, and another who gained power through the virtual environment—sit opposed to one another. Miraculously, the one with power derived entirely from the virtual realm is the one in a commanding position of authority. While The Mittani lounges in his fabric chair in front of the camera—spiky gelled black hair, and a chin capped by a goatee—Zulu sits tensely and leans as far away from The Mittani as possible. Both of them agreed that the negotiations over the past two days had been fraught.

"We were a little mean," The Mittani says at one point in the video. "I'll go ahead and allow that we used strong language. It was actually maybe a little bit awkward when we watched the expressions on the faces of the CCPers as they read our statement."

The statement signed by the Council of Stellar Management reads,

"We believe that the situation that has unfolded in the past week has been a perfect storm of CCP communication failures, poor planning and sheer bad luck. Most of these issues, when dealt with in isolation, were reasonably simple to discuss and resolve, but combined they transformed a series of errors into the most significant crisis the EVE community has yet experienced. We hope that this meeting will be the first step in the restoration of trust between CCP and the EVE community, and we will keep the community informed as to CCP's efforts in delivering on the commitments they have made to us and to you."

It was a humble end to a period that witnessed a player revolt that cost CCP roughly 8% of its subscriber base.

A testy truce was agreed to in Iceland with both parties publicly agreeing that CCP had no plans to abuse pay-to-win business models. However, the meeting and the Jita Riots had exposed a deep vulnerability in the EVE Online business model. What happens if the players within the virtual community begin to organize? Is CCP really in charge if the players are willing to cancel their subscriptions en masse? In early online games the slang for "developers" was literally "gods" because they ultimately controlled the off-switch for the game and could change it in any way they saw fit. The Jita Riots had raised a fascinating question: who was in control of the off-switch of EVE Online? The early online game devs would often shut down their virtual worlds after time had passed, interest had waned, or the workload became too great. CCP Games no longer had the option of walking away. It had built a company of 600 employees off the success of EVE, and now multiple other game production teams were being financed by its success. It's not melodramatic to say that the sudden failure of EVE could have had notable consequences for the nation of Iceland. CCP now had investors and employees with children to consider. No person or group of people at CCP was capable of making the choice to shut down the game.

The players, however, had shown that they ultimately could, or at least that they could briefly put it into cardiac arrest. Player protests of this sort could affect earnings, and even a hiccup in payments could drastically disrupt operations at CCP.

EVE Online itself had encouraged the players to form these sprawling organizations, and now those very organizations were the grassroots of a movement that had spread across the star cluster and had miraculously proved that the EVE community was somehow more in control of EVE than CCP Games itself. If the game died, it seemed, it wouldn’t be a result of developer intervention. It would be because the players walked away.

"October 5 marked the official end of the Summer of Rage with two devblogs," wrote Matterall—an EVE journalist and podcast host of “Talking In Stations”—in a retrospective. "The first was from CCP Zulu who communicated an ‘immediate refocusing of all the EVE development teams on EVE’s core gameplay: spaceships.’ EVE Online’s Winter 2011 expansion, which would come to be known as Crucible, would include a laundry list of improvements and fixes. The second was from CCP CEO Hilmar Veigar Pétursson who issued his own apology letter admitting, 'I was wrong, and I admit it.' It was a humble end to a period that witnessed a player revolt that cost CCP roughly 8% of its subscriber base. However, it was also the beginning of a new era when CCP would become better communicators, more engaged with the players, and more focused on fixing the issues that had piled up for so long."

CCP Games was left in Iceland with a new reality to contend with. The temperature in the community was finally beginning to normalize and the protests were dispersing. Still, the number of subscriptions to EVE Online was down 8%. This after hoping that Incarna would usher in a new era of CCP Games in which EVE Online would finally become "the grand dame of gaming."

Instead, the community realized its position of power, and CCP Games was forced to face an internal reckoning. With subscriptions declining for the first time in almost ten years and progress slowing on both DUST 514 and World of Darkness, CCP Games announced a 20% staff cut. One in five of CCP Games' 600 employees was to be laid off immediately.

Andrew Groen is an EVE Online historian who has turned its endless conflicts and bitter betrayals into a series of books that chart EVE Online's violent in-game history.

Most Popular