Enemies in Spec Ops: The Line never actually throw grenades, and other game design secrets

Find out why you can survive bullets in BioShock that should kill you.

Remember that metro train in Fallout 3 that was actually, according to the game's code, an "arm" inexplicably worn on the head of an ordinary character model? My favorite stories about games give us a glimpse at the kinds of workarounds and crazy tricks game developers pull to make their games fun (or to make them work at all). Designer Jennifer Scheurle gave a talk on that subject at GDC, drawing from a viral Twitter thread she started last fall. She pulled out some of the best examples from that thread to explain in her talk, and these are the PC games that stood out to me.

BioShock

The first bullet a splicer fires at you in BioShock will almost certainly miss. This lets the designers spring surprise attacks, but still give the player time to react to incoming fire. It's the kind of thing you likely never notice while playing the game, but is blindingly obvious once you see a video example. A splicer will waltz up and miss their first shot from short range.

Scheurle got her information from Ken Levine, who said the first shot will always miss, but Bioshock's AI designer weighed in to say it's actually a bit more complicated than that. Enemies have an accuracy curve that increases the longer they're in a battle, so they start extremely inaccurate and become quite accurate over the length of an encounter.

The more surprising tidbit, though, was that a single shot will never kill you in Bioshock, but instead bring you down to 1 percent health. If a splicer targets you with a tommy gun and unloads—a bunch of bullets hit you in sequence—you're probably going to die, because you'll be taking a hit at 1 percent damage. But that first shot won't do it. This gives the player the rush and tension of just barely surviving, without feeling like a cheap hit took them out.

It's the kind of game design balance that isn't realistic or necessarily "fair." We think all bullets should do the same amount of damage, right? But that small touch is something most players will probably never notice, and if it works as designed, means Bioshock's combat will be more fun.

Gears of War

This was the only secret that totally shocked me, and it was one that generated plenty of discussion in the Twitter thread last year. In the original Gears of War, the developers realized that something like 90% of players would never touch multiplayer again if they didn't get a single kill in their first couple matches. So how do you ease new players into a very high skill, challenging multiplayer mode? The Gears team decided to give them an invisible buff.

Players who haven't gotten a multiplayer kill before get a damage bonus on their shots, akin to the higher damage you get from Gears' active reload mechanic. Except the new players didn't actually have to pull off an active reload to get that damage buff. Once newbies had a couple kills, the game would dial back their bonuses.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

This one made some people mad because it's a competiive game and not fair. But some designers argued the advantage for new players was there to offset the many advantages skilled players had already—knowledge of the map, the ability to pull off active reload, and so on.

Spec Ops: The Line

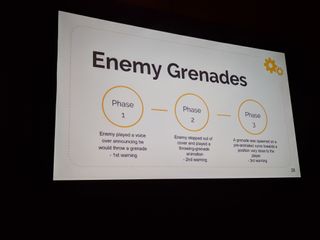

This was my favorite detail of the talk, because it touches on two things: designers taking shortcuts that players will never notice, and bending the truth to make the game more fun. In Spec Ops: The Line, enemies will shout at you to let you know they're about to throw a grenade. They'll step out of cover and trigger a wind up animation. But they never actually throw a grenade at you.

Instead, the grenade simply spawns in midair, on an arc headed towards you. Scheurle explained how it all worked, thanks to input from a designer at developer Yaeger. "Nobody has found out since the game came out, and I'm spilling the beans today," she said.

This implenentation of grenades fulfilled the game design goal of having grenades as a threat, but was much less work than programming a full ballistic system for the AI. As Scheurle said, "it didn't really matter."

Yaeger hid the system by having grenades spawn at the feet of an enemy if you shoot them before the "throw" takes place. That helps complete the illusion.

In Spec Ops, enemies react to grenades tosses at them and run away to look smart, but not outside the AOE so they still get hurt. #UX is #gamedesign magic, it’s beautiful! 😍 #uxsummit #GDC18 @Gaohmee pic.twitter.com/siebmA4PPCMarch 19, 2018

The trick that makes Spec Ops more fun is also pretty simple. When you throw a grenade at enemies, there's a reaction radius that will tell the AI to run away. That's called the panic radius. Smart AI! Except, the AI is actually programmed to stay within the blast radius, so they'll still take damage. That's not so smart. But isn't it way more fun to blow up the AI with a grenade than it is to miss?

There are plenty of other tidbits hidden inside Scheurle's Twitter thread. If you missed it, give it a read. And then try calling yourself from inside Surgeon Simulator:

In Surgeon Simulator we hid many features to incite curiosity: for instance, if you dial your real phone number in the game, it calls you.September 3, 2017

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).

Most Popular