End of days: GameSpy's forgotten games and the gamers keeping them alive

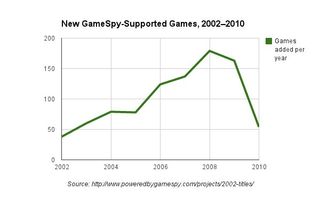

GameSpy began in 1996 as a fan-hosted server for the original Quake. By the early 2000s, GameSpy was the online multiplayer platform, adding dozens of games every year. More than 800 games have used GameSpy to connect players and manage servers. GameSpy's ubiquity spawned dozens of offshoots such as Planet Half-Life and FilePlanet. Even in the age of Steam, the GameSpy catalog remains an extensive library of the great multiplayer games of the past 15 years. That all ends tomorrow when GameSpy shuts down.

More recent games, much-loved favorites, and games with even a modicum of popularity are being ported over to Steam-based servers to continue their lives. This is not a story about those kinds of games. This story is about the games that have become living museums to the Way Gaming Was—from before Call of Duty became an annual franchise, before the rise and fall of Rock Band, and before anyone paid a single microtransaction for horse armor. Games from this era relied on GameSpy for their multiplayer servers, and many of them will die when those servers go offline on May 31.

I wanted to talk to the people who still play games that, for the rest of us, are nothing but fond memories. With my anti-virus on high alert, I dove into the seedier corners of the Internet to dredge up old install files, seek out the last guardians of a dying age of PC gaming, and ask them: Why this game? Why now? Why still ?

Do they even know that the end is coming?

Nostalgia

Scott Kevill has been working to set up multiplayer servers since 1997, which actually makes him a contemporary of GameSpy. While GameSpy peaked and crashed, it's only recently that Kevill's company, Australia-based GameRanger , has kicked into high gear. GameRanger now has over five million members and serves connections to over 120,000 players a day. The big hits pay his bills, but it's the older gems that drive Kevill.

In the past few months, GameRanger has been working overtime to add support for GameSpy games that would otherwise be forgotten to the annals of pixelated YouTube Let's Plays or a forlorn Wikipedia stub. Halo: Combat Evolved and Star Wars Battlefront 2 have been two recent high-profile additions. The service now hosts almost 700 games, 325 of which are set to have their GameSpy-based multiplayer modes go offline tomorrow. I ask him why people still care about old games.

“Nostalgia is a big one,” he says. “The games had an impact on them at a certain point in their lives.” Adding support for these games is “a lot of work for little reward,” and players don't always make it easy. “Nostalgia has a double-edged sword in that people are upset that the online experience is not as big as it was at the game's peak. As if bringing back those original servers would magically bring back all the old players and the old experience, and it just doesn't work that way.”

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

I recently took a tour through the GameRanger servers for Halo: Combat Evolved. On an average weeknight, I saw three full servers and a half-dozen others with progressively smaller populations. All told, about 100 people were still playing the great-grandaddy of the Halo franchise, which came out on PC in September 2003. When half a million people log into Dota 2 every night, it puts two games of Capture the Flag and four pairs of friends into stark perspective.

People still play, though, because of nostalgia. Every player I talked to referenced nostalgia as their first reason for logging in. Two players in Rune, a hack-and-slash multiplayer melee game from 2001, stopped chopping heads off long enough to tell me explicitly: they still play because they still have fun with friends they met in-game. “Friends and a sweet community,” a player with the tag of Gamora told me over the in-game chat. “If they left, I wouldn't be staying in this game for one more minute.”

Gamora's friend Pan told me that the group does play other games, but they still like playing Rune because of the fond memories. They also play Chivalry: Medieval Warfare , but they have more fun with Rune's antiquated combat systems. While I spoke with Pan and Gamora, a total of six people were logged into Rune's servers.

Star Wars: Battlefront 2 had a more active community over the Memorial Day weekend—the last full weekend the game would be live on GameSpy. I found Lucas Verdugo and his friend fighting a battle on Hoth with around 20 other players. I joined a Skype call, which Lucas uses to chat with friends while they play, to ask him about it.

“It was a nostalgia purchase,” Verdugo told me. He'd originally played it on his long-lost PlayStation 2, and had only recently bought a copy for PC. “I love Battlefront so much because I'm able to create my own storyline if I want to [in the galactic civil war].” Battlefront 2 was the first FPS game he ever purchased. “Star Wars is my favorite franchise of all time. When I first started playing this game, I was ecstatic.”

Verdugo had actually not heard that GameSpy was shutting down until I asked him how he felt about it, something I felt immediately terrible about. There was a silence as he did a web search for articles about the shutdown. His recent purchase and rekindled enthusiasm for a game from his youth were about to get cut short, and I'd accidentally dropped the news. While Battlefront will live on thanks to GameRanger, the still-active community will most likely be fragmented and much smaller.

New games don't measure up

Players still think of these aging games like they did when they were new, with the fondness they felt for them when they were young and in love. I'll be blunt: a lot of these games have not aged well. To someone who hasn't played a Battlefront game since Episode 3: Return of the Sith was in theatres, the graphics are messy and the gameplay is floaty. To the fans, they're the hallmarks of a golden age.

“It's the first multiplayer game I ever played, so nostalgia is part of it,” Dylan Mason says about Battlefront 2. I met him and his friend while I shot at Ewoks—rendered in 2005 graphics as waddling gray turds with spears—on Endor's forest moon. Mason told me on a Skype call that he is disappointed that the servers are shutting down before the new game—rumored to be shown at this year's E3—has a chance to come online. He jokes that when the servers go offline, he'll probably cry a bit and then play against bots for the next week. But he's also somewhat antagonistic about more modern games. “None of them have the same feeling as Battlefront,” he says. Battlefront is his main game for multiplayer.

His friend, Bill Bish, chimes in: “I played it as a little kid growing up, and it's one of the best Star Wars games ever.” He hopes that EA and DICE will make the next Battlefront game incredible, but he's skeptical. “I really hope they can top it,” he says, “but you know...”

I do know. I know exactly what he means because a fan of DICE's other multiplayer shooter franchise, perennial Call of Duty competitor Battlefield, told me almost the exact same thing a week earlier. The player, whose online tag is RIICKY, is part of a group of modders working to save Battlefield 2 from obsolescence . He still plays the second entry in the Battlefield series all the time with a large community of friends. He expressed the same nostalgia I saw in all of my interviews: “For me, I was kinda raised with the game.” RIICKY also longs for a time before Battlefield became “dumbed down for the masses” to appeal to a wider audience. “Business is business and I understand, but it's sad to see the core values get pushed aside... I still can't find even recent Battlefield games to be a replacement to Battlefield 2.”

I ask Kevill about this angle, and he agrees that he's heard it a lot from GameRanger members. “Sometimes it's the gameplay hasn't been matched by newer offerings—even if the graphics are not that new and shiny,” he says.

Art history

The modern mega games industry is the biggest it's ever been. The games of the GameSpy heyday generation were created by smaller teams than the modern Call of Duty blockbusters, but they still represent the work of hundreds of artists, programmers, writers, and animators. If even the oldest, least-loved B-movies can find a home on Netflix, doesn't the artistic output of these developers deserve to be saved?

I asked RIICKY if he thinks he's saving a piece of gaming history. “I definitely do. Even if it wasn't really that much of a popular game compared to other titles that were active at the time. It definitely shaped the way the new Battlefield games were made and I'm sure how the Call of Duty series and many others responded to them.”

Half a world away in Australia, Kevill thinks so too. “For me, that's actually a big part of it, he says. “It's one thing to preserve the games themselves years later, but multiplayer was part of these games as well. As the trend shifted to have the online experience intertwined with the rest of the game, more and more the games have become unusable without those online services. They're a part of history that need to be preserved.”

Kevill may have a soft spot for unloved technology. He collects old computer hardware, including a collection of TRS-80 computers that I would love to visit. He doesn't think of himself as a collector by trade, though: it's just that the more popular stuff already has someone looking out for it.

“[With these old games] it kind of felt like, if I didn't, no one else was going to. And that would be a great pity to have history vanish.”

Most Popular