Our Verdict

Over quickly and hardly exhilarating, but illuminating in a way games rarely bother to be.

PC Gamer's got your back

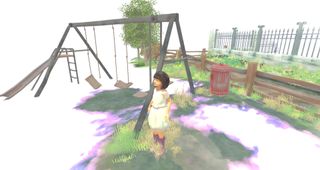

What is it: A third-person exploration game starring a blind girl

Publisher: Team17

Developer: Tiger & Squid

Reviewed on: i5, GTX460M, 4GB RAM

Expect to pay: $15 / £10

Multiplayer: n/a

Link: Official site

Some of the most valuable if not enjoyable artworks are those that force us to reconsider something we think we know well. Beyond Eyes has changed how I think about walls. In most games, they’re things to crouch behind, leap over and blow up, or (if you’re an NPC from Alien: Isolation or Dead Space) smear with instructive graffiti in your dying moments. In this, a game that casts you as a blind girl searching for her cat, they almost feel like friends.

Walls, after all, take you places even as they slow down exploration. Walk along one and you might come to a corner. Turn the corner and you might come to a door. The comfort such predictability offers is palpable in Beyond Eyes’ context-sensitive animations: drift near a building and your character, Rae, will reach out tentatively, fingertips brushing the surface for reassurance. It’s one of many ways in which Tiger & Squid’s brief but stirring adventure transforms your appreciation of 3D space.

Rae lost her sight in an accident some time before the story begins. Once a giddy extrovert, she has become something of a hermit, her sole remaining contact with the world beyond her garden a chubby ginger feline named Nani. One day Nani doesn’t visit as usual, and Rae leaves the garden to search for him. It seems a laughably simple framework to build a game around—but then, this is an observation that’s coloured by the complacency of the fully sighted. To a girl in Rae’s shoes, a stroll down a woodland path can be every bit as unnerving as scouring a tomb in Dark Souls, and Beyond Eyes’ greatest feat is to express this in a way those with unimpaired vision can grasp.

Where other games about blindness have tackled the subject by limiting themselves to audio, Beyond Eyes deals in visual metaphors. Each environment in the game begins as a measureless expanse of white—a backdrop that, unlike the customary cliche of blindness as eternal night, rouses curiosity rather than dread. Everything Rae can hear, smell or touch is manifest on this landscape as a pleasing gush of watercolour. Grass and flowers seethe into existence underfoot as you step forward. Houses erupt from a splash of brickwork, textures spreading across the hidden structure like time-lapse footage of a coral reef. Animal or mechanical noises pulse in the distance, temporarily exposing patches of road or treetop as Rae picks up on how sound waves are affected by contact with their surroundings.

This is stunning to witness, as homely as the supporting technology may be. It’s also a source of enduring uncertainty. You may, for instance, ‘see’ what’s happening inside a building or enclosure before you realise that the structure itself is there. You’ll ‘see’ the river bubbling beneath a bridge before you discover that you’re able to cross it, stepping out cautiously into what at first appears to be empty air. Moreover, Rae’s perceptions are tinged by her innocence—the slightly saccharine, storybook aesthetic isn’t just a presentational gambit, but a commentary on the protagonist—and the gap between perception and reality can be memorably unpleasant. An early example is what seems at first to be fabric gaily flapping on a clothesline. On closer inspection, the object reveals itself to be a scarecrow. Rae’s fear and surprise at such discoveries are touchingly conveyed via body language, rather than couched in dialogue—she’ll stoop, hugging her sides, when the world refuses to play along with her expectations.

Plenty of games set out to be entertaining. This is one of the few that wants to change you.

This is as much a game about learning to live with life’s occasional ugliness, in other words, as it is learning to live without sight. The player’s precise role in amongst all this is engagingly hard to pinpoint. At times you feel like Rae herself, struggling to make sense of the geography; at others you’re more of a guardian, leading her by the hand. The story’s initially confusing refusal to broach the question of her parents is telling, in this regard—it leaves that role open for the player to assume, if you choose.

Beyond Eyes is a game I want you to play—especially if you have young children—but one I struggle to grade. While illuminating and restful, it’s rarely ‘fun’ in the same way that, say, a Tomb Raider game is fun. The pace is necessarily ponderous, yet the story can be completed in an evening, and while there are a few traditional puzzles, they’re extremely simple, more there for variety’s sake than to provide a genuine challenge. But then, judging Tiger & Squid’s debut by the standards of more straightforward entertainment media is missing the point a little. Plenty of games set out to be entertaining. This is one of the few that wants to change you.

Over quickly and hardly exhilarating, but illuminating in a way games rarely bother to be.

I desperately hope Dragon Age: The Veilguard, Baldur's Gate 3 and Disco Elysium inspire more RPG devs to reject the traditional drip, drip, drip of DLC and expansions

Warren Spector found working on his cancelled Half-Life episode 'a little frustrating', but he'll be 'forever grateful' to Valve for keeping his studio alive

How Fish Is Made is the most disgusting horror game I've ever played, and it perfectly captures 2024