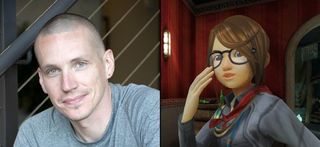

AAA to Indie: BitMonster's Lee Perry

Lee Perry has been exploring new territory.

Formerly Senior Gameplay Designer on Gears of War 3, Perry is one of BitMonster Games 's six founding members. But Bitmonster's debut title is bereft of gargantuan firearms. Instead of steroid-infused marines in heavy armor, Lili has a bespectacled teenage girl as a protagonist. It's one of the many changes Perry and the other co-founders have experienced after their amicable departure from Epic Games.

Perry compares the transition to an indie environment as something similar to moving from an driving an automatic to switching to a car with a manual transmission. "You're more connected to the project, but there's far more to keep an eye on," Perry says. "There aren't 150 other people to rely on when you need something like a random sound effect or logo.

"There are no safety nets," he continues. "Granted, prior to Epic, every company I worked for shut down or at least closed the office, so stability isn't that great in the industry to begin with. But, with indie development, you stack that on top of the fact that, 'If you're not doing it, it's not getting done,' and it's exhilarating and terrifying. There isn't a dedicated sound guy over there you just hand off requests to. You have to just do it.

"In many ways, it's like home ownership. You think, 'I can't fix a broken sink!' Then you read up on it, head to the store, and you just figure it out. When the process is done, you're better off for it."

An industry veteran, Perry worked on high-profile games like Unreal Tournament 2004, Deus Ex the Gears of War trilogy. Though game design has always been a part of his aspirations, Perry explains that it wasn't always an option, saying, "The reality is that nobody wants to hire someone to come up with 'ideas.' Virtually everyone has projects they want to do already. So, I started out as an artist, animator, modeler, etc. I worked on gaining practical skills to execute visions. By the time I was fully a 'designer,' I had been an art director, lead level designer, track lead... As a result, I could talk to people in different departments with their own language."

"The reality is that nobody wants to hire someone to come up with 'ideas.'"

But AAA development isn't without its problems, according to Perry. "The most challenging thing about working in that environment is 'industry risk aversion,'” he says. “Having sanity checks and processes are great, but at some point, you're drowning in the debates, the limitations, the meetings, and ultimately, the feeling you're spending the best years of your life creating something that is very hard to consider yours.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"I've been fortunate to work with some talented, big names in the industry, but the harsh reality for most people in that situation is that no matter how hard you work, no matter how well your work is received, your accomplishments are largely reflecting on the big names associated with any AAA company.”Perry continues: “As long as that's the case at a AAA company, you're not likely to ever get a shot at creating a new IP of your own. If that's your true passion, it can't work. With the indie world, you eat what you kill, and the more successful you are, the more freedom you're creating for yourself."

Perry pauses before quipping, "The negatives of being indie are often the same as the positives. You're eating what you kill so, logically, if you're not killing it, you're starving."

Another too-frequent downside for AAA development, Perry suggests, is being subject to shareholders and bureaucracy. "With AAA projects, you're far more likely to be laid off after working insanely hard than you are to see big rewards. You're ultimately part of a larger machine, and it's depressingly common for talented developers to be treated as little more than variables in spreadsheets."

Perry characterizes his previous employer differently, though. “Epic was more unique simply because they were respected, stable, and successful," he says. "They didn't have to bend to the whims of publishers and shop projects around to stay afloat.”

In spite of these cautionary tales, Perry isn't without praise for large studios. "The most rewarding aspect of AAA development has always been knowing that many people out there will experience your work and hopefully be influenced by it. If you're fortunate and are working on a huge hit, you know the work you do on some aspects of the game are going to be enjoyed by millions of people. That's a really empowering feeling. You can look at a level and think, 'If I add a one second pause here, I will use two months of human life over the course of millions of people playing this game.'"

That said, Perry doesn't seem to regret migrating to the other side of the fence. If anything, he sounds like he's considerably satisfied.

“We've cranked out a ridiculous amount of work over seven months for six people in a basement," he says. "I don't think people believed those numbers when showing the project around at Casual Connect. We learned so much making Lili about all kinds of game creation we wouldn't normally be exposed to. We were all digging into our past skill sets that have been gathering cobwebs in an AAA environment where you typically do a specific task often. It was challenging beyond belief, but when it's done, you can sit back and feel like you've really advanced your skill set and grown as a game creator.”

Perry's advice to anyone looking to make a name for themselves in a big studio is to temper enthusiasm with maturity and a healthy dose of self-awareness. While talent may be important, the ability to take criticism is paramount. Companies need to know who they can work with, not just what they can work with.

“Don't ever take offense at someone asking you to do an art test or code test," Perry advises. "It's not an ego thing. They're simply trying to cut out people who would...oh, take offense at being asked to do something."

Describing Epic as a “notoriously tough place to get into,” especially in its formative years, Perry says that many joked that the hiring process was nearly “Seinfield-ian” in nature. “If you didn't impress virtually everyone, you had no shot. I started off doing some contract work for them on the side, and they really loved what I was doing so I had an edge with people using my work as opposed to just coming in with a portfolio.

“My biggest suggestion to people is know the company you're looking to apply for, and do something tailored for them,” Perry says. “Make them feel like you really want to work for them specifically, not just any game company.”

"My biggest suggestion to people is know the company you're looking to apply for, and do something tailored for them."

When questioned about whether its previous involvement with AAA productions had been helpful to the fledgling team, Perry's answer was one shaded with hearty agreement. “It provided a nice PR bump out of the gate which can be pretty critical to getting your game visible. Twenty years of working with all kinds of tools was also just a great foundation for getting things done quickly. The six of us here have done about everything at some point, and I can't imagine how much harder it would be without that experience to pull from.”

Most Popular