Our Verdict

An approachable and thought-provoking meditation on life's only certainty.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it A simple mortician sim which aims to open up conversations about death.

Expect to pay $15/£11.39

Developer Laundry Bear

Publisher In-house

Reviewed on Windows 10, 16GB RAM, Intel Core i7-5820k, GeForce GTX 970

Multiplayer None

Link Official site

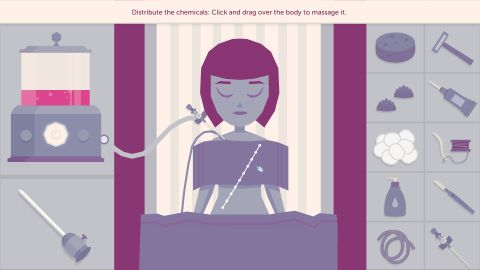

I've just hooked a cadaver up to an embalming machine, dragging a cannula to the carotid artery and attaching the necessary tubing for fluid drainage. As the machine whirrs I trace patterns with my mouse over the cadaver, mimicking the action of massaging the body so as to evenly distribute the chemicals.

A Mortician’s Tale is a curious project—it takes the death positivity movement, especially the work of people like Caitlin Doughty and The Order Of The Good Death, as its inspiration and marries it to the simple inputs you’ll find in those free browser games where you heal horribly mangled Disney princesses or deliver babies. What you end up with is a thoughtful tool for presenting ideas around death.

The core of the game is concerned with de-stigmatising death, returning to it as a natural thing which it’s okay to think and talk about instead of something to hide from.

You join a family-run funeral home as a mortician. Your first job is preparing a body for a closed casket service and burial where the family has requested no embalming. All that’s required of you is to wash the body with a sponge and leave her with a colleague to be dressed.

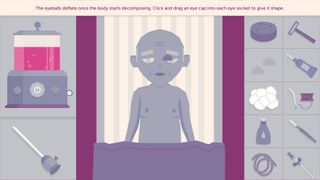

Cremations require you to remove items—pacemakers, jewellery and so on—then run the remains through a cremulator to produce the ashes. Embalmings involve the most steps and require you to think about the logistics of presenting a corpse. For example, one step is inserting eye caps. Eye caps look like spiked contact lenses. The curvature of the cap helps give the impression of a rounded eyeball under the eyelid and the spiked surface helps hold the eyelids in the closed position.

As with the browser games it references, all of the actions are heavily simplified, compulsory and repetitive. In A Mortician’s Tale I think that actually works—it lends a sense of ritual to the game which feels important, plus the fact that nothing is optional means that players aren’t given the space or the temptation to disrespect their cadavers. You must go through all the steps, including paying your respects at the service. The game itself is short enough that even if you chafe against the lack of choice I don’t think it's a deal-breaker.

The simplifications do mean the game doesn’t confront putrification, mess, disfigurement or gore but I think here—although that might be one of the realities we shy away from—presenting death full-force might detract from the idea of opening up conversation and making death less abhorrent.

The influence of the death positive movement and, particularly, sites like The Order of the Good Death and Death and the Maiden is clear. You'll find it in the far-ranging death-related subject matter which flows through your character’s inbox—mushroom suits, water cremations, behaving at a funeral…

You’ll also see it in the messages your character’s friend sends about her work in a pathology museum and it’s reflected in the approach of your initial employer—a small family-run business—and the subsequent intrusive upselling and impersonal attitude of the megacorp which acquires it.

You'll even see it in the look of your character, Charlie, whose dark hair with blunt bangs seems to reference both Caitlin Doughty and Sarah Chavez—prominent voices in the death-positive community.

Without direct experience of the funeral industry I can't speak to how accurate the story is—suffice it to say that it presents small-scale, green, personal funeral experiences which take account of individuals as the ideal and an impersonal profit-driven funeral corporation as bad. As with the mortician processes, that feels heavily simplified and the ending inevitable. But the flow of engaging and curious information through Charlie’s inbox about so many facets of death will, I hope, still end up tempting players to investigate further and allow the game’s ideas to spill outside the confines of its play space.

So far, in the time since playing I have Googled: "pathology museum near me", "eye caps for embalming", "home burials", "massage for rigor mortis", "how deep do you have to bury a body?" and "can I bury a body myself?". All of those produced fascinating results. Alas, my current search—"can I bequeath my teeth to a friend?"—is not yielding such a clear answer.

An approachable and thought-provoking meditation on life's only certainty.

I desperately hope Dragon Age: The Veilguard, Baldur's Gate 3 and Disco Elysium inspire more RPG devs to reject the traditional drip, drip, drip of DLC and expansions

Warren Spector found working on his cancelled Half-Life episode 'a little frustrating', but he'll be 'forever grateful' to Valve for keeping his studio alive

How Fish Is Made is the most disgusting horror game I've ever played, and it perfectly captures 2024