In 1998, Thief: The Dark Project defined the stealth game

A look back on the game that gave players the tools to sneak, not to fight, and the impact that had.

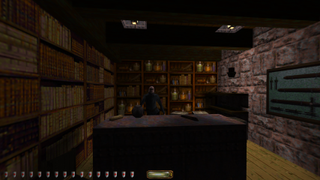

Footsteps in the dark. Mutterings under breath. The sound of a bowstring, pulled taut and released. To think of Thief is to think of its sound design, from the simplest combat effect to the gravelly narration of Stephen Russell’s Garrett as he hides in the dark, observing a city so corrupt that a man like him can be its unsung hero. It’s to remember that city, nameless and broken, where the cold steel and hot fires of the Metal Age sit atop the weeds and lost secrets of ancient pagan culture and zombie boneyards. The quiet moments. The frenzies as a plan goes wrong and shouts of “Taffer!” fill the night sky. The perfect getaways and the desperate escapes.

There had been stealth games before, but little that took things to this degree—to make the shadows your armour and patience your best friend.

Despite all this, if there’s one thing that defines Thief, it’s in the title. Many games, including successors like Deus Ex and Dishonored, are fundamentally built on playing things your way. You get the tools to sneak around if you want, but you also get a sack of guns and explosives, super-powers to break the rules of the world, and levels and enemies built to allow you to explore them. Thief instead strikes a deal. It gives you the tools and experience of a master criminal, but only so long as you’re willing to play the role.

Garrett may be godlike in the shadows, but he’s a mediocre swordsman. A blackjack to the back of a guard’s head is a guaranteed takedown, but alert, they’ll call in backup and easily take you down. On higher difficulty levels, you even face Garrett’s pride as a bonus challenge—he won’t kill, not out of squeamishness, but professionalism. He is, after all, a thief rather than a murderer, and good enough at it never to need such a crutch.

Stepping into his boots back in 1998 was a whole new experience. There had been stealth games before, but little that took things to this degree—to make the shadows your armour and patience your best friend. Your tools, ranging from water arrows to extinguish torches to rope arrows for climbing, were tools in the truest sense, with each mission taking place in an open plan location designed to let you pick your own path and decide your own tactics.

Even the very first encounter, Lord Bafford’s Manor, is a multi-levelled building with multiple approaches, floors and secrets, with your only guide being a hand-scribbled map of what Garrett thinks is inside. The second, Cragscleft Prison, features a whole mine complex you barely even need to enter.

If Thief has a problem, it’s that occasionally it loses confidence in itself, with fantasy elements like the undead and giant spiders sitting awkwardly next to the more steampunk city up top, and with a plot involving magic and paganism that quickly veers away from the pure satisfaction of breaking and entering. Thief II: The Metal Age didn’t remove the fantasy elements entirely, but it did wisely double-down on the other side, with Garrett now facing the steam-powered horrors of a genocidal Mechanist and generally sticking to the civilised parts of the city—raiding a party, robbing a bank, kidnapping and eavesdropping, and sabotaging the villain at every turn.

The sequel's maps took the series to a whole new level, with new tools like a clockwork eye that could be used to scout terrain, and maps designed around concepts rather than story first (the story then largely written around them, not that it mattered). Those maps were were built to be even more non-linear and open than the first game's. Now we really got to experience the City firsthand, with guards and other overheard characters now regularly piping up with their stories, and the original game’s approach to difficulty—not just additional enemies, but challenges like stealing a certain amount of treasure and the previously mentioned no killing rule—making for incredibly replayable missions.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Looking Glass could make even a basic guard feel like part of the world, rather than just another enemy.

Again though, so much of this rested on Thief developer Looking Glass Studios being able to focus on specifics. Garrett’s trusty bow for instance was unlike any other weapon at the time—its feel, its sounds, the thunk of its arrows all carefully and lovingly made to feel both satisfying to use, and a worthy weapon of choice for a master thief. The blackjack as a tactical weapon. The sword, designed to be good enough to let you handle the occasional screw-up, but not go in swinging. Every tool had its purpose and its limits, with success coming from mastering them all and escaping.

By being able to focus their AI on handling a stealthy character, rather than a jack-of-all-trades, Looking Glass could make even a basic guard feel like part of the world, rather than just another enemy. Their banter as you hid in the shadows gave them a sense of history that we now take for granted in games like Dishonored (did that guy ever get his own squad after what happened last night?). In 1998, it was a huge step forward.

Even basic footsteps contributed to the feel, with different materials underfoot echoing with different sounds. Admittedly, it did make Garrett sound a bit like he’d gone thieving in metal clogs, and his ‘moss arrows’ should probably have been replaced with a nice pair of slippers or something, but that’s easily forgotten when you’re fleeing from guards, shooting a rope arrow out of a crypt, clambering up and belting for the exit before they can get back upstairs.

It’s that kind of moment, emergent yet natural, that really defines Thief as an experience more than simply a series of missions in an FPS. While the original occasionally suffers from a lack of confidence, Thief II strides into the night with an absolute cocksure certainty that what it’s doing is right. It’s tough not to get swept away by that. Even now it remains the master of the shadows, and the Thief that stole and kept our sneaky black hearts.

Most Popular